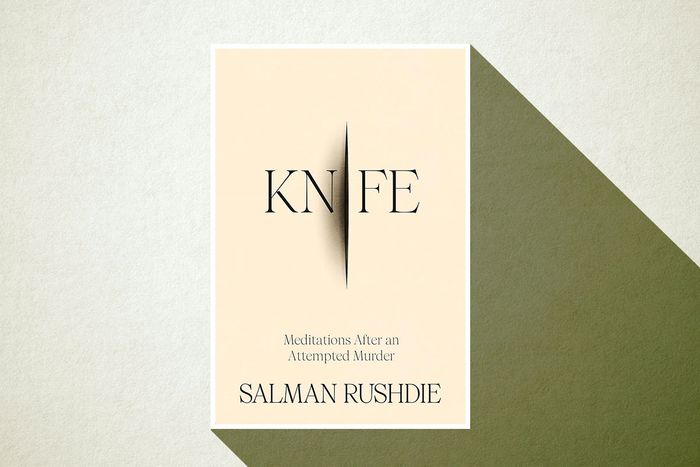

There’s a moment in Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, that reads like a Rorschach test. A few weeks after a young man stabs Rushdie multiple times at an event in Chautauqua, Rushdie’s agent, Andrew Wylie, visits the convalescing writer and tells him: “Eventually you’ll write about this, of course.” Rushdie hedges. Wylie repeats, “You’ll write about it.” Some readers may take Wylie’s comment as the solace of a friend who knows and loves the artist: Sorry you nearly died, but at least you — unlike most people — can make something of it. Those who know Wylie’s reputation as “the jackal” of American publishing might, however, see his comment as career counsel for a Great Man: Write it; I can sell the hell out of it — and it’ll affirm you as a free speech near-martyr.

Which way you answer that test may have to do with which Rushdie you believe is writing this memoir — for there are many Rushdies, as the man himself is well aware. There’s Great Writer Rushdie, the often brilliant, if uneven, novelist who has been nominated for the Booker Prize seven times, has won it once, and is the rightful heir to Gabriel García Márquez and Günter Grass. There’s Great Man Rushdie, the historical figure knighted by Queen Elizabeth, primarily known for living much of his life under a death threat. There’s “liberty-loving Barbie doll, Free Expression Rushdie,” as the author puts it in Knife, who, after the Ayatollah Khomeini slapped him with a fatwa in 1989, became a free-speech advocate. There’s also Celebrity Rushdie, the bon vivant who relishes brushing shoulders with Václav Havel and Bono, who made cameos in Bridget Jones’s Diary and Curb Your Enthusiasm, and whose marriage to the model and cooking-show host Padma Lakshmi was litigated across the pair’s respective memoirs. More recently, there is “Near-Martyr” Rushdie (an epithet the author uses in Knife), an aging public intellectual who nearly died on August 12, 2022.

So it is fair to ask: Which Rushdie wrote Knife? Is this new, buzzy memoir the work of a man securing his legacy? Or of a man reflecting on a writing life interrupted by stranger-than-fiction events? Knife is in part about — and in some sense itself is — a battle between the two most prominent Rushdies: Great Writer and Great Man, artist and advocate, private person and public figure. At its best, the book speaks to what it has been like for someone who thinks of himself as a writer by vocation and a free-speech activist by conscription to try to make art, not to mention a life, under extraordinary circumstances. At its worst, Knife can leave the reader feeling unsure of which Rushdie it speaks for, which Rushdie we should remember.

In August 2022, just before the stabbing, a then-75-year-old Rushdie was preparing for the publication of his 15th novel, Victory City. He also had notes for a 16th, to draw on Franz Kafka’s The Castle and Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. But after the stabbing, fiction had to wait: “Something immense and nonfictional had happened to me,” Rushdie writes in Knife. “Until I dealt with the attack, I wouldn’t be able to write anything else.”

Rushdie’s resentment at losing precious months with his fiction is understandable. Ever since the fatwa, the author, who often prefers to transmute autobiographical material into fabulism, has faced a problem: His real life is so absurd it demands setting down in print. What writer worth their salt would let someone else narrate their own story? People have tried: Márquez once had his agent call Wylie to announce that he was writing a novelization of Rushdie’s life, to the latter’s chagrin. A zealous Rushdie even won an apology from a police driver after suing for false claims in the driver’s book. His desire to control his own story may account for why his book about his years hiding under the fatwa, 2012’s Joseph Anton: A Memoir, was so artless, a tome of grievances and gripes; that was Great Man Rushdie laying claim to his own existence as intellectual property.

Like Joseph Anton, Knife is Rushdie’s attempt to deal with an absurd and traumatic event, “owning what had happened, taking charge of it,” an endeavor to “answer violence with art.” Unlike Joseph Anton, Knife is taut, readable, and, thankfully, not petty. In 209 pages, Rushdie recounts the hellish morning in Chautauqua, two hospital stays, and a year of rehabilitation. During these 13 months, Rushdie had surgery on his neck, hand, eye, liver, and abdomen. He had his right eye sewn shut, endured months of physical therapy to regain the use of his left hand, weathered a cancer scare, and published Victory City. He also completed Knife. Meanwhile, “the angel of death,” as he writes, has been paying visits to his writer friends: Milan Kundera and Martin Amis died last year, Paul Auster is gravely ill, and Rushdie’s “younger-brother-in-literature,” Hanif Kureishi, has become paralyzed.

Given the circumstances, it is miraculous that anyone would manage to write anything coherent about such a recent trauma, let alone anything good. And Knife is often good. The first chapter, in which Rushdie recounts the attack itself, contains some of the most precise, chilling prose of his career. Remembering the sight of the black-clad figure making for the stage, Rushdie recalls thinking, “So it’s you. Here you are,” and then, “Why now, after all these years?” His would-be assassin is “a sort of time traveler, a murderous ghost from the past.” For the past few decades, Rushdie has acted as though the still-extant fatwa does not hang over him: “I achieved freedom by living like a free man,” he writes, but the assailant, Hadi Matar, whom Rushdie refers to only as “the A.” — “I have found myself thinking of him, perhaps forgivably, as an Ass,” he writes — is a negation of Rushdie’s asserted freedom, violent reality slicing through the illusion he’s maintained for decades. Wondering why he froze in Matar’s path, Rushdie writes, “The targets of violence experience a crisis in their understanding of the real.” Rushdie the artist has always excelled at this sort of writing, at making personal sense of spectacle and terror, whether he’s describing India and Pakistan going to war, Khalistani extremists hijacking an airplane, or a chauffeur murdering a counterterrorism officer in Kashmir; “reality,” he’s written, “isn’t realistic.” Indeed, Knife is at its strongest when Rushdie-the-novelist narrates the material of his own life.

The boldest of these novelistic moves come when Rushdie writes about the A., the then-24-year-old Lebanese American who told reporters he had only read two pages of Rushdie’s writing and watched some YouTube videos before setting out on his homicidal mission. Rushdie obsesses over the gaps in the A.’s story, the opportunities for characterization, the uncannily literary fact that he and the A. spent only 27 seconds together but are now yoked for life. Turning over the detail that the A. canceled his boxing-gym membership the night before coming to Chautauqua, Rushdie registers the A.’s awareness that he was ending his own young life while attempting to end the author’s. Rushdie marvels darkly at the fact that the A.’s bag on the morning of the attack was filled with an assortment of knives, as though the young man were waiting to make his final pick that day, a chef selecting the appropriate instrument.

In the memoir’s standout chapter, Rushdie imagines himself having a series of conversations in the Chautauqua County Jail with the A. He seeks to cast his assailant as a literary character, “to make him up, make him real,” and wonders if the A. is like Othello’s Iago, a slighted man turned destructive, or André Gide’s Lafcadio, who murders “for no reason at all”? Rushdie revels in stuff that would be funny if it hadn’t almost killed him. The fictional A. says Imam Yutubi radicalized him. Noticing Matar’s bizarre stated motive — he found the author “disingenuous” — Rushdie quotes The Princess Bride at the A.: “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.” As Rushdie wrote in “Is Nothing Sacred?,” the speech Harold Pinter delivered on his behalf in 1990, less than a year after the fatwa, since Rushdie could not appear in public at the time, “The most secular of authors ought to be capable of presenting a sympathetic portrait of a devout believer.” Here, not for the first time, Rushdie sketches such a believer. As Shakespeare gave Iago some very good lines — “I am not what I am” — Rushdie gives the A. a few: “You are only a little devil — don’t flatter yourself” and “At school there’s this experiment with iron filings and a magnet. When you point the magnet, all the iron filings fall in line … The magnet is God. If you’re made of iron, you’ll point in the right direction. And the iron is faith.” At this point in Knife, Great Writer Rushdie works in the service of Free Expression Rushdie. The novelist uses his ample literary talents to explore what cannot be rendered by polemic: a picture of two people, two lives, caught up in civilizational forces beyond them. How tragic, how absurd; how very Rushdie-ish.

The rest of Knife is less precise than the material about the A. The word meditations in the title may be a preemptive defense against the accusation that, as a complete work, Knife is somewhat inchoate. But the lack of clarity in Knife’s mission can feel distracting. Early on, Rushdie says Knife will try to make sense of his near-death: “Whatever the attack was about, it wasn’t about The Satanic Verses … I will try to understand what it was about in this book.” A compelling premise, but it’s not actually what Knife does. The material about the A. concludes when Rushdie declares, “I no longer have the energy to imagine him, just as he never had the ability to imagine me.” He turns away from his villain: “The knife attack told us all we needed to know about the A.’s interior life.”

Here, the Great Writer puts down his pen too soon. Rushdie need not have more deeply inhabited Matar, but there is complex social context around the man and his radicalization that Knife might have explored more fully to truly comprehend the author’s near death. The Muslim world has changed wildly since the fatwa was issued in the wake of the Iran-Iraq War: the Gulf War, 9/11, the “war on terror,” two forever wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the rise of the Islamic State are just a few of the major developments. Matar is of a new generation of terrorists, following a “many-headed and many-voiced” fundamentalist Islam, as Rushdie’s A. describes Imam Yutubi, not acting on the singular dictum passed down by the ayatollah.

The discourse on free speech has also changed substantially since the 1990s, and even since 2012’s Joseph Anton, but Rushdie barely touches on the historical context surrounding the stabbing: “The First Amendment was now what allowed conservatives to lie, to abuse, to denigrate. It became a kind of freedom for bigotry.” Rather than try to reconcile these “new ideas of right and wrong,” or consider the political forces that converged around him, Rushdie declares himself tired in the days after the attack: “My voice was weak and faint.” This is understandable, after all he’s been through, but it makes one wonder whether he’s framed the work erroneously — or whether the book needed more time.

I am not arguing that Free Expression Rushdie ought to have penned some sort of political pamphlet. It’s Rushdie the writer I crave, the novelist known for depicting the convergence between the political and the personal — the “we” and the “I.” Rushdie told David Remnick last year that his memoir of the attack would be an “I” book, rather than employing the third person of Joseph Anton. That in itself is not a bad thing, but the magic of Rushdie’s “I” narrators, from Midnight’s Children’s Saleem Sinai to The Moor’s Last Sigh’s Moraes Zogoiby, is that they have often stood in for a larger “we.” Knife might have benefited from more “we.” That ability to make history intimate is his greatest talent as an artist; the gift predates the fatwa. It may be cruel to expect Rushdie to craft something that both addresses society and feels artistically transcendent in the face of such a personal crisis. But he has managed this feat before, writing Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990), his marvelous children’s book about a storyteller who has lost the power of speech, while in hiding. (Of course, he was far younger then and not recovering from a murder attempt.)

The final chapter, entitled “Closure?” feels especially rushed; in it he returns to Chautauqua in September 2023, where his wife, the writer Rachel Eliza Griffiths, takes his photo in front of the jail. Then they visit the amphitheater where he was attacked in order to “face up to the unbearable knowledge, common to all human beings, that it would never be yesterday again.” He feels himself “making my peace with what had happened, making my peace with my life.” His wife tells him, “I could see that this was good for you.” Good how? He doesn’t say.

In Knife, Rushdie twice mentions Philip Roth’s retirement. Before entering his 80s, Roth stuck a Post-it note on his computer declaring “the struggle” over. Roth’s struggle was purely artistic, taken up of his own volition. But Rushdie’s struggle, by contrast, is as many-headed as Imam Yutubi, and he has not engaged with all of it by choice. So though Great Writer Rushdie may someday be able to declare his own struggle over, Free Expression Rushdie’s struggle will never end; his is a public drama that cannot be resolved by a single piece of art. If Knife sometimes feels like it was hastened to press, if its conclusion reads like an epiphany forced on deadline, it’s probably because Rushdie, reasonably, wants to spend his remaining years on the struggle he actually chose, not the one he was coerced into. “The greatest damage” he’s suffered, he writes in Knife, is that his life may have eclipsed his art — that all those very public Rushdies “distract attention from the books themselves” and even “make it unnecessary to read the books.” Here’s hoping that’s not true, because Rushdie is at his best when he is a novelist — when he’s not arguing about free expression but expressing himself freely.