Over 500 pages into A Court of Mist and Fury, the second book in Sarah J. Maas’s wildly successful “A Court of Thorns and Roses” series, the protagonist, Feyre, finally hooks up with Rhysand, an ancient Fae lord with batlike wings and a deep well of emotional trauma. Rhysand ravages Feyre on a table covered in her art supplies — then scoops her up and carries her to a bathtub, where they wash off the paint they’re now covered in. Maas narrates from Feyre’s point of view: “Rhys picked up a bar of that pine-tar smelling soap and handed it to me, then passed a washrag. ‘Someone, it seems, got my wings dirty.’ My face heated, but my gut tightened. Illyrian males and their wings — so sensitive.” As she starts washing Rhys, she glances over his shoulder into the bathtub. “At least the rumors about wingspan correlating with the size of other parts were right,” she tells him.

This scene, like most sex scenes taken out of context, reads as baffling or laughable or both. The bathtub. The innuendo. The wings! Within the full arc of “ACOTAR,” though, it represents the culmination of an epic fairy-tale transformation. Feyre begins the series absolutely in love with a different man, a golden faerie named Tamlin, and it’s only after intense trauma and a grueling effort to rebuild herself that she realizes protective, possessive Tamlin’s all wrong for her. It takes her nearly a full book to accept that she belongs with Rhysand — the kind of faerie who has tattoos on both knees to remind him he kneels to no one. Until, of course, he gets on his knees for Feyre.

Maas’s work has been a fixture of the fantasy aisle for over a decade — she published her first novel, Throne of Glass, in 2012. Recently, though, she has become unavoidable. Her books have sold more than 13 million copies and are both regular No. 1 New York Times best sellers and the subject of endless social-media discourse, Goodreads analysis, and YouTube explications. (More than one Maas superfan has knee tattoos to match Rhysand’s.) The author has now published eight full-length “Throne of Glass” novels and five “A Court of Thorns and Roses” books and three installments of her most recent series, “Crescent City” — the latest book, House of Flame and Shadow, is out today. While the “Throne of Glass” books were always popular within YA and fantasy spaces, “ACOTAR” was the series that broke through — thanks to its combination of a slower fantasy-world build, Beauty and the Beast–inspired framing, and a surge of BookTok attention. All of these novels are behemoths, regularly approaching 200,000 words and often filled with half a dozen groups of characters who wander across fantasy landscapes in pursuit of love and destiny and prophecy and revenge.

Elements repeat from one series to the next: There are faeries. There are humans who could become faeries. There is a threat of authoritarianism, violence, and the suppression of the hero’s magic. There is a heroine who must come into her own power in order to save her lover (and the world). That lover is often hundreds of years older than her, mourning the loss of a previous partner, and powered by immense dark magic (and he usually has wings). While “Throne of Glass” and “A Court of Thorns and Roses” are often shelved as YA, both series include more explicit sex than is typical of that marketing tier. Ideally, the sex happens with someone who could be the heroine’s mate, a true forever partner, and their transcendent bond goes beyond simple intimacy.

Vulture Guides

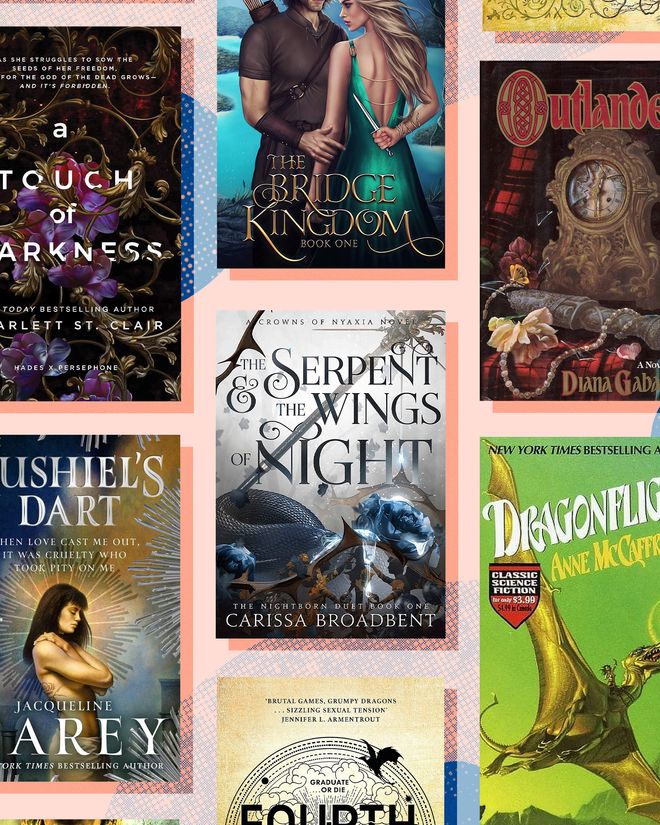

Now, Maas is leading the pack for “romantasy” — the romance-plus-fantasy genre that is exploding as writers like Jennifer L. Armentrout, Carissa Broadbent, Rebecca Yarros, and many more turn out blockbusters. The majority of the most popular writers are white women. Some of their tales lean more dragon than faerie. Some are inclined toward vampires. These kinds of novels have been around since at least the 1960s, when Anne McCaffrey started writing books about dragons whose ecstatic mating rituals spark similar feelings between their riders. (McCaffrey preferred for her “Dragonriders of Pern” series to be called science fiction, not fantasy; litigating the distinction would require a long tangent about spaceships.) The quality these stories share is an emphasis on a happily-ever-after ending within a fantasy world and as much focus on fantasy plotting as on the romantic arc. The two are twined together, equally crucial to the endgame: a simultaneous orgasm of structural devices.

One of Maas’s innovations has been to glue it all together with a trauma plot. Trauma and its integration into the self are as fundamental to her books as, say, the need to stop an evil king from destroying all humanity. It’s a prominent feature of “Throne of Glass,” in which dispossessed faerie queen Aelin inks tattoos of her lost friends onto her back to help her live with her grief. Feyre continually loops through her memories of past pain, experiences that fuel both her romantic awakening and her ability to decode the enormous plot unspooling around her. In “Crescent City,” the half-human, half-Fae protagonist, Bryce, must come to grips with her best friend’s murder (which she does by uncovering the corruption in her city while also falling in love with her angelic, winged investigative partner). At a cultural moment when the trauma plot feels so familiar, it’s no wonder a series that treats it as a lingua franca has become so widely read. Fantasy has a surfeit of Chosen One narratives; in Maas’s work, the Chosen One needs to learn to Choose Herself.

Maas has been working toward this moment for decades. Now 37, she grew up in New York, where she went to Dalton and studied creative writing and religious studies at Hamilton College. She started writing Harry Potter fanfic as a young teenager; at 16, she began drafting the book that would become Throne of Glass, posting chapters on the forum FictionPress before eventually selling the novel to a traditional publisher. She now does very little press, but in 2016 she spoke about her early influences on a podcast. “Buffy and Sailor Moon, those were my two favorite shows. I think it was because they were about these young women, these very unlikely heroines,” she said. “Getting to see these women who were like me: not that great at school, girlie girls who loved feminine things and then turn into these badass warriors where their feminine qualities don’t cancel out their strengths.”

Feyre begins “ACOTAR” as a determined, desperate young woman trying to save her family from starvation. Like all of Maas’s protagonists, she’s quickly thrust into a world of magical conflict and comes to both love it and be changed by it. After she realizes she no longer wants to be with brooding magical daddy Tamlin, the chief obstacle over the next hundreds of pages won’t just be another evil ruler who threatens her and her loved ones — it will also be the grief and trauma that hold her back from being her best self. Maas devotes significant real estate to each stage of healing. Although Rocky-esque training sequences with stern yet loving mentors are often involved, the focus is on how physical transformation is mirrored by emotional resilience. While writers like Broadbent and Danielle L. Jensen also play with trauma and healing, Maas is the queen of this mode: Her novels may have all the sprawling maps and battle scenes and legendary swords and surprise betrayals of a hundred epics before them, but their highest priority is feelings, a constant throbbing heartbeat.

Maas’s fans approach all of this with Talmudic attention. Her lore spurs on readers who obsess over close readings and speculate about crossover: Are the bat-winged people from “ACOTAR” actually demons from the world of “Crescent City”? Two characters from two separate series both have eyes that look like “leashed lightning” — are they related? The emphasis on fated mates fuels the shipper communities, who theorize about future pairings: Will the next “ACOTAR” book be about Feyre’s sister Elain? Who is Azriel’s mate? Are Hunt and Bryce really mated, or is it different if one of them is an angel?

It helps that Maas’s sentences are short and full of repetitive and replicable themes and tropes. (For example, magical back tattoos — Bryce, Feyre, and Aelin all have them.) Her work can easily be clipped for illustration or titillation — her 1.5-million-follower Instagram account is populated with quotes from her books that are designed to heighten audience anticipation for upcoming releases: “After so many brushes with death, it was only a matter of time before it stuck.” “Never again would she be weak. Never again would she be at someone’s mercy.” “His laugh was like dark velvet. ‘Where would you like me to lick you, Quinlan?’”

It hardly matters that Maas’s world-building can be inconsistent. “ACOTAR” seems to be set in a preindustrial time — until the second book, when Feyre suddenly vomits in what appears to be a modern toilet. There are plenty such opportunities for confusion. If Crescent City, which has computers and guns and elevators, runs on magical immortality energy, does that mean there is no electricity? And in that case, how did they invent the chips in their cell phones? Why can’t faeries, who have remarkable healing knowledge and the ability to survive catastrophic injuries, perform a C-section? These unresolved questions come to feel like dares or deliberate traps. Why get hung up on rules when you could give yourself over to emotion?

So much about these books is mediated by their overwhelming length. When they’re really hitting, and the culmination of some longed-for sexual pairing arrives just before the final battle, they take on a delicious anesthetic quality, accompanied by a beautifully empty, absorbed acceptance. Maas’s work taps something down deep. They promise true love, remixing fairytale archetypes into relationships with contemporary contours. They dwell on found families and depict women facing deep stress and overcoming it. The endless descriptions of power structures and subspecies, the catalogues of swords and cauldrons and Dread Troves and prophetic books: It’s all built to sustain post after post of speculation and comparative close reading.

And yet the dominant experience — for those who are onboard for sex scenes in which people keep growling “You’re mine” — is some middle space. Maas’s work thrives when you’re so immersed you’re beginning to develop a theory about why she keeps using the word gossamer or at least to accept that it’s a world where gossamer is omnipresent. Reading her requires a direct conduit to a younger self who would stay up late and dog-ear all the sexy bits to show friends the next day at school. It requires an abandonment of the ironized mind — while some soft, tender part of you breezes through page after page of descriptions of a spunky heroine who is the only one who can rescue her dark faerie lord.