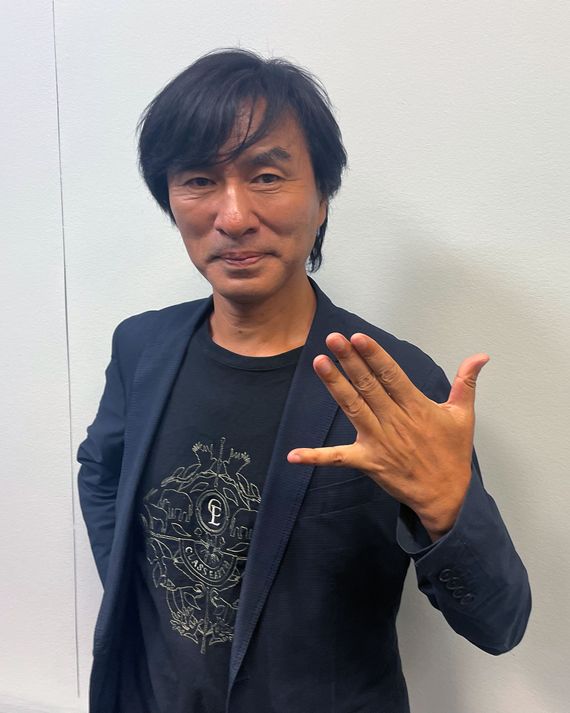

Hollywood workers represented by IATSE Local 839 — a.k.a. the Animation Guild — are in active negotiations for the future of their industry. Among the issues on the table is artificial intelligence and whether and how it can be used by studios to create the kinds of imagery once only realized by human hands. In Japan, which rivals the U.S. in animation revenue and output, workers face punishingly long hours, low pay, and a dearth of union representation that could address some of these issues. Recently, Shōji Kawamori, one of the industry’s elder statesmen and the creator of the Macross franchise, told me he’d be “perfectly fine” using AI in some of his own work.

“From a cost and speed perspective, I think it’s inevitable that AI is going to be used,” he said in an interview at Anime NYC in late August, where he was a guest of honor. “Putting aside the controversy, I think it’s just going to happen.”

Kawamori is known for the clarity, depth, and style of his mechanical designs, a process developed over his 47-year career. His influence on anime is so vast, his successors often appear like replicas: The Diaclone transforming robots he designed predated Transformers, and his series Super Dimension Fortress Macross was adapted into the first season of Robotech — both igniting a passion in the West for Japanese action animation and transforming robots alike. At Anime NYC, he joked that 1986’s Top Gun featured a heroic fighter pilot dating a female superior set to a catchy soundtrack, noting that Macross came out four years earlier. Today he continues to shepherd the Macross franchise through new titles and appearances like his latest in the States.

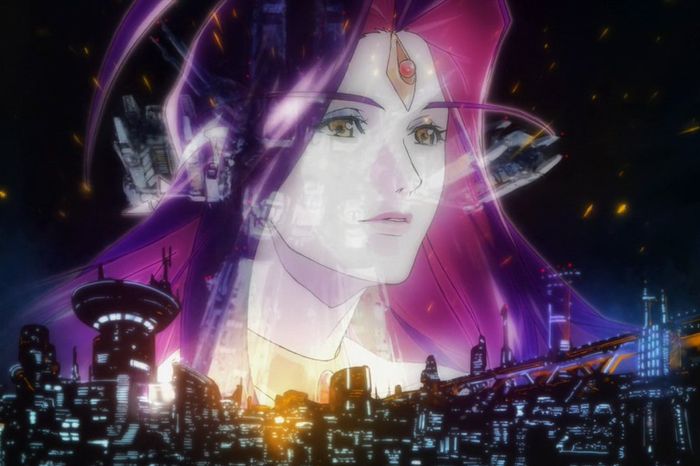

Kawamori isn’t an AI optimist. We chatted a few hours before a Japan Society screening of Macross Plus — his 1995 film about an AI hologram that threatens humanity — which is also being rereleased on Blu-ray September 30. At Anime NYC, he shared stories about the terrific lengths he and his fellow artists go to create their anime. His action-animation director Ichirō Itano once blacked out when the pair flew fighter jets on a research assignment, then animated the experience for Macross Plus; Itano would also shoot fireworks from his bike to better understand how they flew in motion.

But Kawamori points out that in the early ’90s, even human animators could not always satisfactorily follow the action animator’s lead: “What was debated among my colleagues was that all these other animators — not Itano — can make missiles move prettily and accurately, but they don’t look painful,” he says of the process on Macross Plus. “When you see one of Itano’s scenes, not only are you visually attracted, but you can viscerally feel when the missiles hit. The question becomes, are the animators actually thinking to themselves, Oh, it hurts? Or are they just copying him because it looks pretty?” To Kawamori, the emotions, and in Itano’s case, a “mind-set” that results in Itano’s action hitting as hard as it does, are still essential to creating powerful art. “Perhaps that is the kind of thing AI might never fully accomplish,” he acknowledges. “But I think AI will eventually get to a stage where it looks like it’s achieved it, even if it actually hasn’t.”

Kawamori knows that AI cannot reproduce emotions, but he sees some aspects of production that involve manual repetitive labor as less creative than others, like “in-betweening,” the sometimes rote process of adding transition frames between a given piece of animation’s keyframes, the shots that define the movement. “Drawing the keyframes is certainly a creative enough process that drawing them by hand — or using CG — is still very necessary,” he says. “But for the intervening frames, getting from one keyframe to the next, the in-betweens, it’s perfectly fine to use AI.”

In-between animators, who tend to be junior compared to the lead animators who work on keyframes, would likely disagree. In-betweening has been described as “the gruntiest grunt work” in animation, and historically, the role has served as a step on the career paths of senior animators, Itano included. But Kawamori looks at this in part as a way to account for labor shortages and financial strain of producing anime. “We are not replenishing our ranks as much,” he says. “There’s fewer and fewer staff able to work on it.” And he sees its use, even “in more actual creative processes,” like keyframing, as an inevitability. “If I ever find it to be very practical, I may find myself using it as well,” he says.

But the artist who’s spent a career telling stories about how humans interact with technology tells me he feels that every technological leap forward makes us more efficient but ultimately less creative. “What’s at the forefront of my mind right now is, as AI itself also continues to evolve, what is it that we feel?” he says. “And through those feelings, what are we actually producing? What do we actually bring forth?”

Kawamori knows machines can maim and divide us as often as they expand our horizons: The SDF-1 Macross ship he designed for 1982’s Macross illustrates that duality, serving simultaneously as a life raft and a war machine. Macross is ultimately a hopeful story, but if AI is as inevitable as Kawamori describes, it portends a future where animation lacks the very soul that ignited those stories — one where studios sacrifice the next generation of Itanos or Kawamoris to it.