This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Simon Rex will be appearing with Red Rocket director Sean Baker at Vulture Festival in Los Angeles on Saturday, November 13 to discuss the film with our critic Alison Willmore. It’ll be a good time; you can get tickets here.

Come to the desert. Past the rock gardens and the suntanned retirees. Past the looming peaks of the San Bernardinos and the windmills that shine like sci-fi sentinels. Past the hippie chicken farms, the ammo shops, the CBD emporiums. Past the point where the pavement stops and the road turns to sand. Here, you will find the man who made “My Dick.”

For two decades, Simon Rex had been on a Gump-like tour of the least prestigious jobs in Hollywood: male model, MTV VJ, sitcom actor, Scary Movie doofus, white rapper, and Vine star. He partied with Paris Hilton when she was the most famous person in America and Charlie Sheen when he was. As you might guess, this was not the world’s most sustainable career path. Things slowed down for a good ten years. Looking back on this period, he thinks of a lesson a meditation instructor once taught him. “When you get a pie in the face, enjoy it. Don’t play the victim. Taste it. Smile,” he says, miming pedagogically. “That’s a good pie.” Not to get all “Tears of a Clown” on you, but he has tasted a lot of pies.

Rex lives off the grid in Joshua Tree now, in a studio made from two shipping containers on a five-acre slice of the Mojave Desert. Having lived in cities his entire life, he felt exhausted by humanity. “I’m not trying to be a recluse,” he says. “I’m hypersensitive. I just feel things too much.” He bought the property in February 2020. It was supposed to be just a weekend getaway, but, well, you know what happened. The vibes got bad in Los Angeles, so Rex sold most of his belongings and moved in full time. He had planned to rent the place out as an Airbnb but has since decided against it: “I didn’t want strangers having sex in my bed.”

It wasn’t just the pandemic that sent Rex into the desert. The truth is he was tired. Of calling his agent, wondering if there was anything out there. Of clawing for any opportunity. Of sitting around hung-over, doing the math on how long he could get by until the next paycheck. Of taking whatever gig came up, even if he hated it, then hating himself for hating it because how many people would kill to be in his place? He had hit a rough patch, but he’d had a good run, reinvented himself several times over. Still, Los Angeles can embalm you. Did he really want to be that washed-up middle-aged guy, forever convinced that this pilot season would be his big comeback? Instead, he would move to the middle of nowhere and see what came next.

On the advice of a buddy, he buried 30 days’ worth of food and bought a gun. The two of them did tactical training like a real-life Call of Duty. He was suddenly roughing it in the high desert with no heat and no AC. He had only two goals each day: Stay warm and eat. There was something pure about it. “Like, this is my commute,” he says on the drive up, gesturing to the prehistoric landscape. He’s dressed in the local style in a weathered white T-shirt and fancy Crocs. “Any time I go to L.A., I start feeling my shoulders tense up. When I’m up here, I immediately — whoosh. This place heals you. Every single night, you’re in a different Salvador Dalí painting. It’s fucking magical.”

Then one day, the phone rang. The man on the other end, director Sean Baker, was offering him a starring role in a movie called Red Rocket. It was the story of an aging porn star in search of a fresh start. For many reasons, Rex was the only man in Hollywood who could have played the part, so it’s appropriate that Red Rocket has given him a reset button too. Instead of weathering a societal collapse, Rex has spent the past few months jetting to international film festivals, being lauded by the giants of cinema, and earning Oscar buzz. A year ago, Rex seemed, even to himself, a relic of millennial celebrity culture; now, like a vintage armchair, he has been plucked out and reupholstered.

“It’s the psychology of, like, if you go out with a rubber in your pocket and think you’re gonna get laid, it doesn’t happen,” he says. “It’s only when you surrender that things happen.”

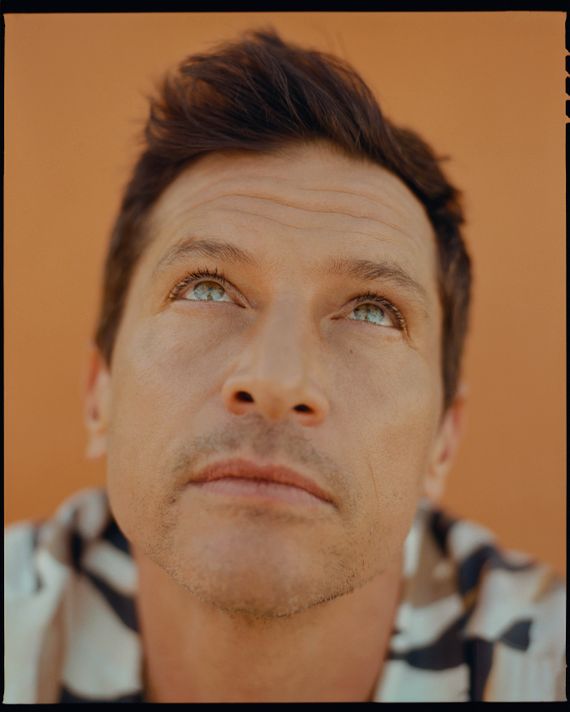

Rex is not just his looks, but his story won’t make sense without talking about them. “Simon was like fully smolderingly handsome,” says the record producer Mark Ronson, who modeled with him in the ’90s. Young Simon had a vulpine stare, piercing green eyes, and abs for days. When, during a guest stint on Felicity, he fixed his gaze on Keri Russell and told her with the utmost sincerity that he wanted to sketch her, you could understand why all thoughts of Ben and Noel flew right out from under her curls. And he has aged well. He doesn’t have the baby face anymore, but the wrinkles have seasoned him.

In Rex’s narrative of his life, he has been “a leaf in the wind” — opportunities come floating out of the sky, and he accepts them without a hint of guile or strategy. At 18, fresh out of high school and living in Oakland, Rex started seeing an aspiring model who indirectly opened the doors to a new life. “It was a crazy time,” he says. He was attending community college and working at a potato-sack factory. “I went to a rave in San Francisco, and I met this beautiful girl. I was enamored with her beauty because where I lived there weren’t a lot of models. Her mom had a Cesarean; when she was born, they cut her out and left her with a really big scar, which was hot.” Talking to Rex is a bit like riding a conversational roller coaster. One moment you’re right side up, the next you’re on a wild loop-de-loop tangent, but you always get back to where you started. (He has been diagnosed with ADHD, which he prefers to keep unmedicated: “I would rather be in my crazy-weird brain.”)

He dropped everything and moved in with her. “We got an apartment in Hollywood, her 2-year-old son’s calling me Daddy — I was in way over my head,” he says. Modeling wasn’t happening for the girlfriend, but all of a sudden, it was happening for him. “I would drive her to castings. I’m sitting with her son on my lap, and the casting director comes out saying, ‘Who’s he?’ She’s like, ‘Oh, he’s not a model. That’s my boyfriend.’ They’re like, ‘He has a good look for this job we need.’ The next thing you know, I was on a flight to Milan. I got her dream, and we didn’t last.”

Was he a good model? “I don’t know how you could be a bad one, unless you just didn’t show up,” he says. “That’s what I didn’t like about it — you just stand there. It’s boring. You have no soul.” One day, another male model couldn’t make a rehearsal at MTV, so the agency sent Rex instead and, wow, now he was a VJ. “I said to them, ‘I have no music experience, no journalism experience, no television-hosting experience.’ They said, ‘Perfect, you got the job.’ Next thing you know, I’m on live TV with a mic in my hand.” Rex was not a natural interviewer; he spent much of the workday stoned. At a Tommy Hilfiger event, he bonked Mary J. Blige in the mouth with his microphone, prompting a death glare from the diva. But being a handsome fuckup was in no way a professional hindrance at MTV. “I immediately wanted to protect his goofy ass,” fellow VJ Kennedy wrote in her memoir. “Simon was a baby, but a beautiful baby with a great heart and a huge penis.” (More on that later.) “Our female viewers love him,” an exec told Newsweek at the time. If you were watching MTV in the mid-’90s, there was a good chance Rex was your first crush.

Gus Van Sant liked what he saw too. The director thought Rex might have the right vibe to play a bully who gets beat up by Matt Damon’s character in Good Will Hunting and invited him to audition: “I get there, I’ve never acted in my life. I’m reading with Matt Damon. I start reading the lines robotically, and he says, ‘Simon, I have to stop you. This is one of the worst auditions I’ve ever seen.’ ” Still, Van Sant spotted a seed of talent and sent him to acting class. “The picture of him in my mind’s eye is storklike, Ichabod Crane,” recalls Rex’s acting coach, Anthony Abeson. “He was not low energy, nor was his presence neutral. He was irreverent, anarchic — but always sweet.”

Rex recalls this period as the best years of his life. At the dawn of the Giuliani era, New York’s downtown model scene was merging with the hip-hop scene, and Rex was in the middle of it all. “You’re bulletproof because you’re 24 years old and you could drink all night, get up the next day, and handle your shit,” he says. Then, in 1997, MTV fired Rex and two other VJs. Declining ratings had thrown the station into one of its Why aren’t we playing more videos? panics, and the bosses, as Time magazine put it, were looking for an “authenticity that veejays like Simon Rex, hottie though he may be, just couldn’t deliver.” This by itself was not a terrible trauma, but around the same time, one of Rex’s buddies committed suicide in his apartment. So he moved to L.A. and accepted a lot of cash from the WB to let it try to turn him into a TV star. He had built-in recognition from MTV and the right look, which is to say he looked a lot like every other guy on the WB. The network gave him a holding deal. “They were throwing money around,” he says. “They would give me six figures to not audition for NBC.” After that arc on Felicity, he played a bartender with a surprisingly large vocabulary in a Friends knockoff called Jack & Jill, then Jennie Garth’s character’s boyfriend on What I Like About You. His big scene in the pilot was wrestling with a mattress. (“Inexplicably allowed to lurk is Simon Rex, the current comedy killer,” sniffed the Chicago Tribune.) Whenever he wanted a gig real bad, he would get a good night’s sleep, study his lines, comb his hair, and never get it. “Then when I’d walk into the room hung-over, didn’t give a fuck, disheveled, I booked the job every fucking time.”

The early aughts are not a hallowed time in American memory, but they were Rex’s time. He joined the Scary Movie franchise, a proudly stupid series of films in which he first appeared as George, a dim but good-hearted hunk who couldn’t stop falling out of windows. The character became a fan favorite, and the series kept contriving ways to bring Rex back, even after George died in a tragic boxing accident. There was a fundamental guilelessness to Rex in all these parts: His characters might accidentally don a Klan hood or get into a fistfight with a corpse, but they went into everything with the best intentions. “There’s no pretense to Simon, no phoniness,” says David Zucker, writer-director of Scary Movie 3. “He knows where the joke is, and he’s smart enough not to wink.”

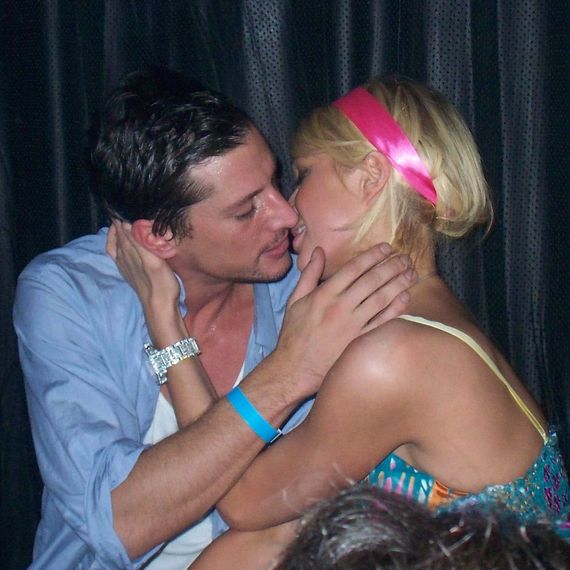

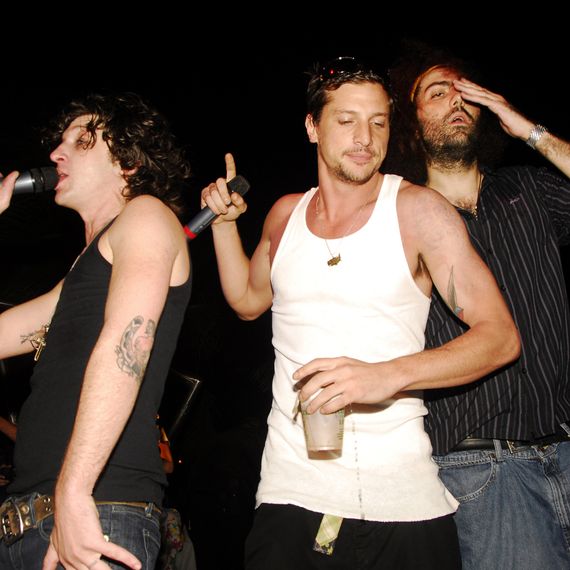

With his newfound financial security, Rex bought a house in Laurel Canyon and, by his own account, did not have to work particularly hard to get by. The rest of the time, he partied hard. Through the L.A. club circuit, he became buds with Paris Hilton. “She’d come out to the club on roller skates. She’d roll up to guys and be like, ‘You’re so hot.’ ” (Tabloid canon says they were dating, but Rex maintains they were just friends who held hands sometimes. Photographic evidence indicates they were maybe more.) Gossip pages spotted him with JC Chasez, Joe Francis, the cast of Laguna Beach. From this scene sprung his side hustle: Through his friend Adrien Brody, “the Pianist himself,” Rex learned how to make beats. Soon he started rapping with a flow inspired by his teenage idol Too $hort. Dubbing himself Dirt Nasty, Rex hooked up with indie emcees Mickey Avalon and Andre Legacy to form a trio that paired lo-fi beats with ironically over-the-top comedy rap. At first, it was just for fun. Rex would burn CD-Rs of their tracks and hand them out to A-listers like Leonardo DiCaprio at clubs. Then Avalon got signed to Interscope, and their track “My Dick” (“My dick, size of a pumpkin / Your dick, look like Macaulay Culkin”) went viral in the Myspace era. “I don’t know if this is a bad thing to say, but it was rap music for white people,” he says. Suburban teens could get a vicarious thrill from the lyrics while at the same time taking comfort in the fact that it was all just a joke.

This era, Rex says wistfully, was the last time nightlife was fun, the time right before camera phones ruined everything: “People standing on a table, getting up and genuinely having a good time, before you’d get busted and tagged at the location. There would’ve been a lot more footage of me being a total wasted asshole.” He is reluctant to talk too openly about those days when a recorder is running. One, he doesn’t want to throw anyone under the bus. And two, he doesn’t want to sound like he’s bragging. But he tells me two stories. The reason he’s more comfortable sharing these, it seems, is because they’re ones where the joke is about him looking like a douche. (When you look like Rex, it is sometimes safer to turn yourself into the punch line before someone else does.) The first came when he was feeling himself so much he went out and bought a Porsche. One day, he was driving down Wilshire, high and a little hung-over, when he caught a glimpse of himself in a reflection. He wanted to throw up: Jesus, look at that asshole. Disgusted, he returned it and got himself a nice, boring Audi.

The other story was from his time hanging out at the Playboy Mansion before he got banned for letting his friends get in with his ID. “There’s no way I’m going to not sound like a dick saying this,” he begins. It was the middle of winter in L.A., and, in a sign that Rex sometimes tried a little more than he lets on, he did something he had never done before or since: He got a spray tan. Then, miracle of miracles, he wound up going home with the Playmate of the Year. Talk about an ego boost, right? “The next morning, the bed looked like a murder scene. All the orange had stained her sheets. She woke me up, going, ‘What the fuck?’ I had to sheepishly put my clothes on while her sheets were ruined. I went from being the man to crawling out of there like a loser.”

Eventually, the Dirt Nasty persona became a poisoned chalice. The character was supposed to be satirical, Simon’s party-boy lifestyle turned up to 11. But while his fans might not have taken tracks like “Baby Dick” or “Animal Lover” at face value, they did come to expect the real Rex to be as much of a flagrant asshole as the guy he played onstage. Touring played havoc with his relationships. “Imagine dating Dirt Nasty — seeing women throwing panties at you, knocking on the backstage door to come over and have a threesome,” he says. “I wouldn’t want that.” Back in Hollywood, his window was closing. His agents would call him about an audition only to find he was on the road in Cincinnati. Then those phone calls stopped. “They were like, ‘Sorry, bro. You’ve been gone.’ ”

He was brought back for Scary Movie V, but even though Rex was one of the leads, he wasn’t on the poster. “Memories are short in Hollywood,” says Zucker. “The studio considered him no longer a name.” He subsisted on indie movies, shitty comedies, web series. In 2016, TMZ captured video of Rex standing outside a Sunset Strip club in sweatpants as a cavalcade of young women unsuccessfully attempted to flirt with him through the universal language of cleavage. To watch it is to witness a man having a midlife crisis in real time: Rex looks almost painfully sober, as though the distance between 42 and 22 is bearing down on him. Since turning 40, he had been in an existential tailspin. He was a grown man with gray hair whose longest relationship had been with his business manager. He quit smoking weed and found he had all these emotions he had no idea how to deal with. “I was trying to hold the mirror up to myself, and that’s a fucking scary thing,” he says. “Am I really just this guy who’s a performative douchebag in L.A.? I spent a lot of fucking nights staring at the ceiling, wondering what I’m doing with my life.” He enjoyed his freedom, but he was learning the downside of a life with few attachments. Should he have gotten married and had kids? Pursued a real career? His days of getting pleasure from partying were long behind him. His fake friends had disappeared when his career dried up, and his real friends had settled down and weren’t hanging out as much anymore; he got the sense their wives considered him a bad influence. “You think you got friends,” he says, “but at the end of the day, you’re really just alone.”

One thing was clear: Rapping to teenagers about doing drugs wasn’t cute anymore. Actors, especially male ones, may be able to stay relevant in middle age, but Rex didn’t think musicians could. “There’s something sad about the old rock star trying to be young and sexy,” he says. “You can’t age gracefully into that, at least not as Dirt Nasty.” He wanted to give it up, but the gigs were his main source of income. (He had gotten into Vine as a lark, but he never made any money from that.) What else could he do?

His own mind was exhausting him, always running a million miles a minute. He tried everything to get it to slow down. “You know how many times I’ve gone to, like, yoga, meditation workshops, self-help books?” None of them really worked. “Certain people are just wired the way they are,” he says. Rex had been exposed to the California New Age scene from a young age and learned quickly that some of it was legit and some of it was bullshit. Both elements are in his blood. His father, Paul Cutright, is a breath-work coach. “My dad’s the real deal,” Rex says, not like the influencers who are just jumping on a trend. He has been doing it for 40 years, since the days of alternative psychiatrist Stanislav Grof. Rex and his dad were never that close — Cutright walked out when Rex was little — but about three years ago, the two of them had a psychedelic experience together, and his dad started telling him about his own father, a spiritual leader who, Rex was led to believe, was not always the most faithful shepherd of his flock. “That’s what happens,” Rex says. “Anyone who’s like, ‘I have all the answers, bust out your credit card,’ get them away from me.”

A safer source of wisdom, he says, is bumper stickers. BE WATER. STAY IN THE MOMENT. RUN TO THOSE WHO SEEK THE TRUTH, AND RUN FROM THOSE WHO CLAIM TO HAVE FOUND IT. “It’s corny New Age shit, but there’s a lot of truth to them.” Whenever he gets stressed out about the turbulence of the modern world, he thinks of something his dad told him at the height of the pandemic. “He said, ‘We’re in the moment between the caterpillar and the butterfly. On the other side of this, there’s an awakening. But right now, everyone’s in the uncomfortable sludgy phase.’ ”

The dream of the ’90s is still alive in Sean Baker’s filmography: small budgets, few stars, no compromises. His movies follow characters on the margins — immigrants, sex workers, hustlers of all stripes — and often feature first-time actors. (“Talk about a fucking avatar of purity,” the filmmaker Kel O’Neill once told me.) But he doesn’t make those desaturated indies where people in poverty sit around and scowl; his movies sparkle with joy and life. Baker broke out with 2015’s Tangerine, a Christmas picaresque shot entirely on the iPhone 5S. His follow-up, 2017’s The Florida Project, is a neorealist gem about a rambunctious 6-year-old living in a motel on the outskirts of Disney World. It appeared on many critics’ year-end lists and earned an Oscar nomination for Willem Dafoe. Crucially, it was also the start of Baker’s relationship with A24, the indie studio behind films like Moonlight, Lady Bird, and Uncut Gems, whose label has become a byword for quality among discerning cinephiles.

Baker’s next A24 project, Red Rocket, was inspired by research he had done on the adult-film industry a few years earlier. It follows Mikey Saber, a down-and-out porn star who returns to his Texas hometown and winds up grooming a local high-schooler. The character’s a sleazeball, constantly spouting off about the comeback he’s sure he deserves. But Baker wanted him to have a queasy likability: Members of the audience should root for Mikey against their better judgment, even while they’re slowly realizing he may be the worst person alive. He’s not a million miles from guys Rex knew in L.A., “the land of narcissistic sociopaths.” Or, for that matter, Dirt Nasty himself. “I’ve been around enough ridiculous, macho … I don’t know if toxic masculinity is the right word, but I grew up around so much of that sort of thing,” he says. “It’s not like I’m playing a professor at Harvard Law. I could speak this language.”

Rex has put a lot of effort over the years into not being an asshole like Mikey. “He’s a horrible person who will do whatever it takes to get to the top,” he says. “I’d like to think I’m not. Unless I’m completely delusional.” Consider the time the British tabloids offered him $70,000 to lie and say he’d slept with Meghan Markle, with whom he had guest-starred in an episode of a UPN sitcom. The same month, a vape company offered him $20,000 to do an ad campaign. He was at the end of his rope, living in a guesthouse in Venice, and could have really used the money. He turned them both down. Now all he has is the memory of doing the right thing — plus a handwritten letter from the duchess thanking him for letting the world know what she was up against.

Baker is about the same age as Rex and had been tracking his career since the ’90s. He loved following the kooky comedy skits Rex did on Vine. They proved he was a survivor. “I was like, ‘Let’s stop pretending this guy’s not talented,’ ” Baker says. “It’s not just the ability to improvise; it’s the ability to improvise and make people laugh, which I find to be genius.” By happenstance, Baker’s sister and Rex had a mutual friend, so it was simply a matter of calling him on the phone, having him submit a tape, and then offering him the part. Rex drove straight to Galveston.

In Hollywood physics, a star is born through a precise combination of actor, role, and moment. Think Bradley Cooper in The Hangover or Channing Tatum in Magic Mike. Rex is not wrong to think Red Rocket could be that vehicle for him. Like all the best star turns, his performance is a mix of things we already knew about him and things we had no idea he could do. Mikey is a vision of early-aughts raunch culture grown desperate in middle age, but his ugliness is always masked with a twinge of humor. In the film’s most painful scene, he reveals his true self in a fumbling, inarticulate monologue. The horrible awkwardness of it, the way it sinks into your stomach, then keeps going? That’s all Rex.

Mikey’s vulnerability is Rex’s, too. “I don’t know if I could have gone to those depths before I got slapped down,” he says. So is Mikey’s motormouthed charisma — whenever the character was about to veer too far into irredeemability, Rex would flash his boyish side: Ooh, a dragonfly! With Baker, he came up with Mikey’s distinctive method of dismounting a bike, hopping off at full speed and letting it careen into a wall. It’s pure slapstick, and it brings down the house every time. Only when you stop laughing do you realize that’s how Mikey treats people, too.

In addition to all the other reasons Rex was a good fit for the part of Mikey, there was this: An uncomfortable number of people knew what he looked like naked. It happened when he was still a teenager, living with the girl with the scar. They had to pay rent, the baby needed to eat, and Simon’s $6.50 an hour as a busboy wasn’t cutting it. So at the urging of his girlfriend, he did two video sessions for gay-porn impresario Brad Posey. Solo stuff, just masturbation. He doesn’t remember how much he got paid, but he remembers it being exactly as much as they needed.

Of course, he’d had qualms, but he would be lying if he didn’t admit a part of him thought it was cool: “It was like rock and roll, Sunset Strip, Mötley Crüe, ‘Rock out with your cock out’ — that dumb shit.” This was the early ’90s. How many teenage boys prepared to jerk off in front of a camera for some quick cash could have foreseen the rapid technological changes that were to come, in which porn would transform from a physical object into a digital one, from something tucked away in shame to something thrillingly available, terrifyingly reproducible?

The tapes didn’t come out for a few years; by the time they did, as Young, Hard, & Solo 2 and 3, Rex had made it to MTV. Newsweek wrote them up, and Michael Musto printed a still of Rex’s penis in his Village Voice column. (Despite rumors, the porn was not why he was fired by MTV, though he did lose out on a few acting opportunities because of it.) Sometimes Rex will say it was 30 years ago and any ill feelings have been worn away by time. Other times, he admits he doesn’t love the way his brush with porn has continued to define him. Girlfriends sometimes used it against him in fights. It was the thing most tabloids led with. “I’m not stupid. I’ll see people be like, ‘Oh, you’re the guy from …’ And they get out their phone and they fucking Google me and then they laugh at me,” he says. He’s aware the release of Red Rocket is about to make the subject inescapable, and while he says his history helped him understand Mikey’s incessant hustle, he reminds me that, unlike the character, he was never in the industry per se. He just made two tapes, then moved on with his life. How many of your orgasms do you remember?

By the time the Red Rocket promo tour rolled around, Rex had been living in total isolation in the desert for months. He’d had a girlfriend early in quarantine, but they broke up shortly after he finished the movie. “I’m not kidding, man. I was losing it,” he says. “I would fucking be sitting there talking to myself out in the desert, responding to a podcast like it was my friend; the lady at the gas station would be my only social interaction in days.”

Within the insular world of European film festivals, the Cannes premiere of Red Rocket was a coronation. Rex walked the red staircase in a navy Armani tux, looking tall and tanned. He seemed as if he belonged there. The film played well in the room, and afterward, cast and crew were treated to the uniquely Cannes experience of a protracted standing ovation. Baker big-upped his leading man with an enthusiastic double-barreled pointing action; unsure what else to do, Rex fidgeted with his bow tie. That night, the Red Rocket team had dinner together to celebrate. Rex ducked out before dessert. The sudden rush of stimuli was too much for him to take. He went back to his room and lay in his bed alone. “My brain isn’t wired for everything that’s happening,” he told me the next day over restorative waters on a hotel lawn. He arrived in leopard-print swim trunks, still damp from a decompressing dip in the sea.

Even the most hardened psyche would have trouble standing up to a roomful of clapping Frenchmen in tuxedos. “The applause and the love, that was one of the highlights of my life,” he said. Rex was crossing the threshold separating one version of the industry from another. In one, you frolic with bikini babes; in the other, you attend galas and tributes. And if — like Leo — you still happen to frolic with bikini babes in your spare time, then at least you’re doing it with gravitas.

There is a certain privilege in prestige. A24’s stable of stars includes Robert Pattinson, an old Harrodian, and Riley Keough, Elvis’s granddaughter. Everywhere Rex goes, cinéastes have been dropping names of movies he hasn’t heard of; like a good student, he has been writing them down and checking them out later. Rex never went back to college, and much of his education has come as an adult. He’s got the autodidact thing of wanting to read every book and listen to every podcast. (When he uses words like ephemeral, he has an endearing habit of double-checking that he’s gotten it right.) He remembers his busboy job in Beverly Hills, when the rich people would treat him like crap because he didn’t cut the lemons right. His festival travels put him back in with those people but with a difference: “Now they want me around.” Reviews out of the Cannes premiere were almost uniformly positive. The Hollywood Reporter said Rex gave a “magnetic full-tilt performance of wired physicality and hypercaffeinated loquacity.” At Deauville, Red Rocket won both the Jury Prize and the Critics Award. The next day, Rex was at a glitzy dinner in Paris. “I’m a shiny object they can say they met,” he says. “I’m still not one of them, but they’re accepting me into their world.”

Rex’s Joshua Tree house has clean modernist lines and plenty of natural light — “an Instagrammer’s wet dream,” he says. Vestiges of the Airbnb idea remain: The compound is full of little stations, almost like an adult summer camp. Over here, there’s a fire pit; up there is a spot for hammocks. For relaxation, there’s an outdoor tub; for entertaining, a dining table carved from Tahoe cedar. A guesthouse is under construction near the driveway. (Rex wanted to build it higher up, but one of his neighbors, a famous superhero actor, didn’t like that it would look out over his property.)

Rex estimates that in the two and a half months since we met at Cannes, he has slept in his bed only three nights. On the drive to his house, he reflects on the journey: “There would be a time in my life where I’d be thinking I was hot shit. Now I’m trying to remain humble. I know this is fleeting.” But it’s impossible not to think, at least a little bit, about the road ahead. “I’ve got to take advantage of this window I have and make the right moves from here,” he says. “That will set me up for the next few years, which could set me up to be comfortable for the rest of my life.”

Rex didn’t actually make that much for Red Rocket. It’s tacky to talk about money, he says to the reporter who keeps asking him about money, but he tells me his fee was less than six figures. (An A24 movie primarily pays in cachet.) But that’s okay. When we get to the house, he tells me another story about money. Before the pandemic, he was traveling around Southeast Asia, paying his way by making Cameos. He would record a few happy-birthday videos for $50 a pop, and that would cover his food and lodging for a while. “To some, that might be pathetic, like, ‘Oh God, Simon Rex is doing Cameos to eat,’ ” he says. “But I felt like the luckiest guy in the world.”

People could call him washed up. Hell, he was saying it himself for ten years. But somewhere deep inside, he knew an opportunity was around the corner. Maybe it would be a sci-fi show no one watched that would pay a couple hundred grand a year; maybe it would be something else. He could just tell it wasn’t over for him. For all his talk about the power of surrender, he believed this: Everything — Red Rocket, Cannes, even the Scary Movie days — was destined for him.

Is that a contradiction? We sit on Rex’s porch and talk about fate. I tell him I think it’s all about the facts you choose to build your own narrative. I tell myself I never saw the most important developments in my life coming, but if I highlighted 12 other things, I could say it was all written in the stars. “I guess it’s not that you were born out of the womb into a destiny, but something carves your path at some point,” Rex concludes.

By now the sun has gone down, and the night is so quiet we can hear our voices echoing off the furniture. I ask him what will happen if the dream doesn’t come true. What if the movie flops, the Oscar buzz dissipates, and his comeback lasts all of one film?

“That’s fine,” he says. “Because look where I am now.” He made a good movie. Even if it fizzles, maybe it will become a cult classic one day. In the worst-case scenario, he’ll be exactly where he was a year ago: living in a place he loves, having made peace with the end of his Hollywood career. The house is paid off, his bills are low. And if money gets really tight and he needs to rent the place out on Airbnb, he’ll survive that, too. “It’s not the end of the world,” he says. “I’d probably get a second mattress and swap it out.”