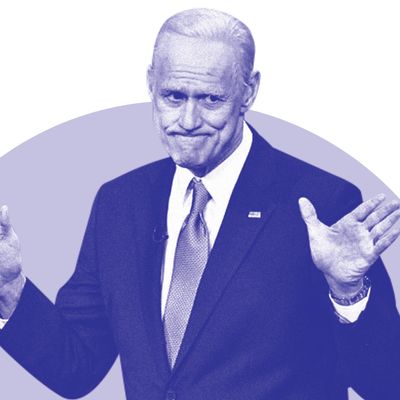

Jim Carrey’s final scene as Saturday Night Live’s Joe Biden impressionist was the most telling moment of his entire short tenure. He stands next to Maya Rudolph as Kamala Harris, declaring himself the victor of the presidential election. Carrey pulls his jaw taught against his face, curling his lower lips over his teeth in an exacerbated old man’s grimace. But the sketch doesn’t take aim at Biden himself — the jokes are about Florida, about all the drunk moms celebrating his victory, and about Trump, sitting at a piano and singing a sad slow version of “Macho Man.”

In the very last moment, Carrey’s impression reveals itself for what it always was. “There are many situations in life, and this is one of them, where there must be a winner, and …” he pauses briefly. His voice rises, his grin turns wicked, “— a looooooser,” he finishes in a growl. He and Rudolph put their fingers to their foreheads in big L’s. “Lo-hooo-ser!” Carrey crows in falsetto. It’s not Biden; it’s Carrey.

It may have been intended as a fun moment where Carrey drops the character, but it fails to land. Because Carrey’s Biden was always Carrey, from the first appearance where he briefly became a cat chasing a laser pointer, to a later one where he plays the president-elect as an energized Mr. Rogers. Carrey’s Biden failed because the central task of a political impression is to have some idea of who that person is.

Pointing out the overuse of celebrity cameos on SNL has become something of a tradition, much like arguing about whether TV shows are actually movies and asking whether Trump is bad for comedy. In 2018 it was a familiar enough topic that Tina Fey took a faux-audience question from Jerry Seinfeld in an SNL opening monologue: “Do you think the show has too many celebrity cameos these days?” The A.V. Club argued last September that celebrity cameos are good because it allows the main cast to steer clear of the clunky political comedy. “‘SNL’ Needs to Ditch Celebrity Cameos and Let Its Cast Tackle Politicians,” Caroline Framke wrote for Variety in October: “Give or take a Fey as Palin or Larry David as Bernie Sanders, it’s now exceedingly rare that a guest star’s political impersonation has much to it beyond, ‘can you believe this person is mimicking that person?!’”

It’s not difficult to see the celebrity cameos on SNL as uniformly disastrous, especially after four years of Alec Baldwin’s repetitive, uninsightful Trump. They aren’t necessarily bad in and of themselves, though. There was something potent in Melissa McCarthy’s Sean Spicer, and there was some happy obviousness to Larry David’s Sanders. Even Brad Pitt as Anthony Fauci carried some oomph, although it’s admittedly easier to sustain oomph over a single joke that only happens once (Brad Pitt is hot; 2020 is so dire that we all have the hots for Anthony Fauci).

Casting celebrities to show up as political cameos on a topical weekly comedy sketch show has much less to do with which celebrity happens to look like Brett Kavanaugh, and much more to do with the baseline task of any impression: It needs to make an argument. The argument doesn’t have to match with real life, and it doesn’t have to present them as absurd, and it doesn’t need to be an arrow aimed directly at puncturing their reputation. But it does need to present a coherent idea of that person.

When a celebrity takes on a political SNL role, the impression always brings their particular persona along for the ride. Anyone famous enough to get cast in the current era of headline-grabbing SNL casting ploys is also famous enough that their celebrity has its own distinct world of meaning. Matt Damon’s Brett Kavanaugh was a pointed demonstration of the justice’s total lack of emotional self-regulation, an argument about his pitiable, grotesque nostalgia for a beer-soaked youth. That argument was bolstered by Damon’s own celebrity image: the good-guy bro; the clean-cut, well-loved youth who went to his fair share of parties and is unfamiliar with the sting of criticism.

The first, blunt line of McCarthy’s Spicer was her gender — Spicer’s weak because he’s being played by a lady! But that impression also came packaged with McCarthy’s public image: her weight, and her characteristic, astonishing energy. Her Spicer was explosive and unpredictable, a methodically exaggerated image of the man who was perpetually on the brink of losing his cool at the press secretary’s podium. Baldwin’s Trump deploys squinted eyes and nightmarish skin tones, and it also carries Baldwin’s reputation as a defensive bully with a temper. (To the extent that Baldwin’s Trump has aged poorly, it’s because he’s done nothing to change it up over four years. Anything gets boring with enough time.)

There’s more to a great SNL political sketch than the combination of mimicry and celebrity image. It’s tough for even a solid impression to achieve Fey-as-Palin canonization without writing that rises to the occasion. Fey’s empty, blinking Palin eyes were already a joke when combined with Fey’s reputation for being much sharper than her Liz Lemon character, but they were catapulted into the cultural stratosphere by the line “I can see Russia from my house.”

There’s an oddball, surrealist vision where Carrey’s could have worked. The actor’s chaos energy and angular hyperactivity could’ve made for an alien, bizarro-world Biden. The disorientation of it alone would’ve been a novel approach to a man whose main feature is that he’s been around forever. But there was no synthesis between Carrey the celebrity, Biden the politician, and the Carrey-as-Biden that appeared onstage. It was a scattered impression that failed to portray Biden as a scattered person.

Whether or not they change opinions or shape the conversation, great impressions help us process major political figures. A failed impression is a failed opportunity, an outlet for release and interpretation that’s been denied. And even without that political weight, it’d be nice to spend the next four years with a Biden impression that hits somewhere nearer to the mark. Woody Harrelson’s Biden, from late 2019, came closer — he gave us a doddering grandfather, physically over-touchy while being mentally out of touch. SNL cast member Alex Moffat is the latest to take on the role, and although his first brief appearance was pretty empty, there’s potential in Moffat’s ability to play good-natured nitwits, people who mean well but have no idea that they’re living in their own warped realities. More significant, though, is Moffat’s relative lack of celebrity. Political impressions by cast members, including Darrell Hammond’s Bill Clinton and Dana Carvey’s George Bush, have had power because they’ve created an argument about those figures, and because their impressions were not eclipsed by their own celebrity. Moffat likewise has room to create a Biden that is more about Biden than about whatever celebrity is playing him, and casting him in that role focuses the comedy away from big stunts. It is the SNL casting equivalent of Biden’s own stated desire for his presidency — to calm things down, to stop the constant political escalation.

It might be a pleasant change of pace to watch four years of an undramatic Biden impression from an SNL cast member unburdened by a huge celebrity image. Or maybe the world will continue at its current fever pitch, and SNL will continue to respond in the only way it seems to know how: by booting him for an A-lister.