This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In a scene near the beginning of Spike Lee’s new Vietnam War movie, Da 5 Bloods, five black American soldiers sit around a radio tuned to an enemy propaganda broadcast, which raises what they have to admit is a pretty good point: African-Americans are far overrepresented on the front lines in Vietnam. “Black GI,” the radio asks, “is it fair to serve more than the white Americans who sent you here?” As the characters mull the ever-relevant question of how much sacrifice they owe to a country that still denies them basic rights, Lee seems to ask viewers to consider another lopsided fraction: Of all the movies that have been made about the Vietnam War, why are so few told from the perspective of black soldiers? (The two most notable previous efforts — the Hughes brothers’ Dead Presidents and the little seen and now hard to Google The Walking Dead — were both released in 1995.)

Hollywood’s whitewashing of war is something Lee, 63, has been thinking about for most of his life. As a kid, the director and his brother Chris would sit in front of the television for entire afternoons “watching World War II films on channel 5, channel 9, and channel 11 here in New York,” he says. “My favorites were Is Paris Burning? and John Frankenheimer’s The Train with Burt Lancaster. But my father would always tell me, ‘We fought in the war too.’ ”

So, in 2008, Lee made his own WWII movie, Miracle at St. Anna, about four buffalo soldiers waylaid in Italy. Lee scraped much of the financing together in Europe after many American studios passed and channeled his father in the opening scene, in which a black veteran watches John Wayne’s The Longest Day on TV and growls at the screen, “Pilgrim, we fought for this country too.” And now, in the midst of a late-career renaissance sparked by the Oscar-winning 2018 hit BlacKkKlansman, he’s made his second war movie.

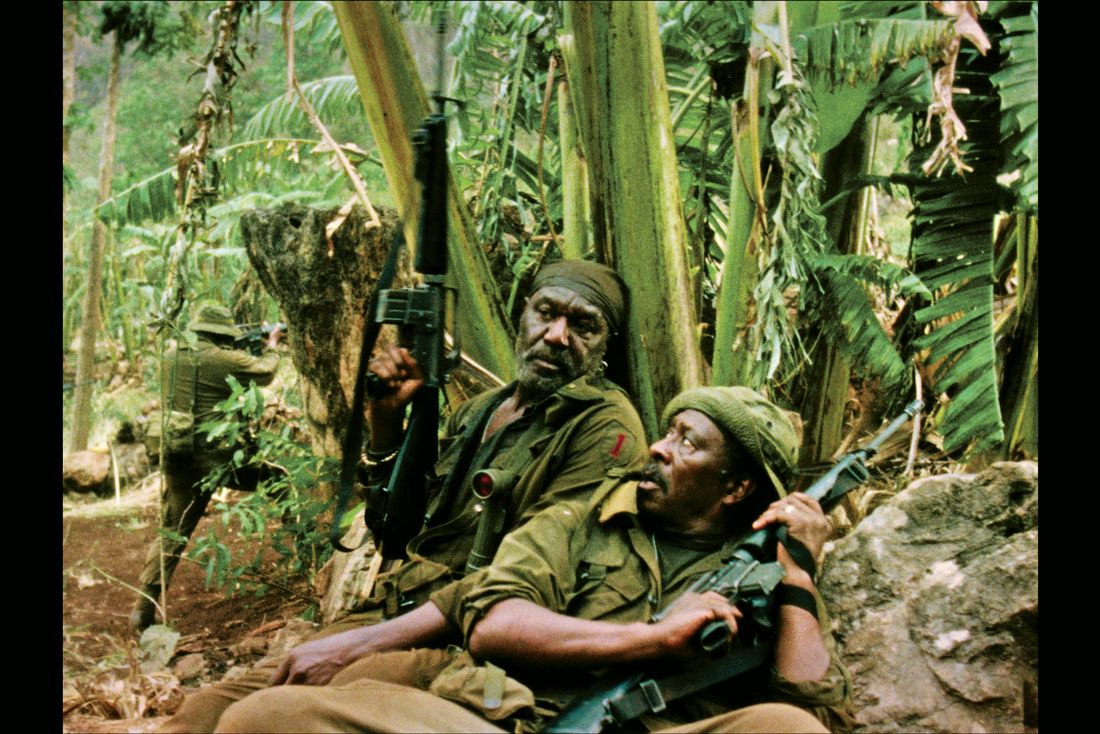

Da 5 Bloods, which premieres on Netflix June 12, is about four black vets — Paul (Delroy Lindo), Otis (Clarke Peters), Melvin (Isiah Whitlock Jr.), and Eddie (Norm Lewis) — who reunite in present-day Vietnam to recover the remains of their commander, Norman (Chadwick Boseman), plus a trunk of gold bars they found and buried during combat. The plot unfolds along two time lines to show both the war’s immediate consequences and its long-term effects on the men (and Paul’s son, David, played by Jonathan Majors, who joins them), whose problems now include addiction, illness, and bankruptcy.

Da 5 Bloods is Lee’s most ambitious film in years, borrowing the setup from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre to frame a story about U.S. racism and imperialism, with tangents and footnotes spanning the entire history of African-American patriotism up to Black Lives Matter.

“The black GIs in Vietnam heard about Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, and they heard about what their sisters and brothers were doing back in the United States, where a hundred cities were burning. Shit was about to go off — and those soldiers wouldn’t have been shooting the Vietcong either,” says Lee. “But that dynamic wasn’t new. It was there in Miracle at St. Anna. It was in Glory. It’s why this movie mentions Crispus Attucks, the first American [of any race] to die in the Revolutionary War. I mean, this year, my brother Ahmaud Arbery, jogging down the street, was shot like a dog. We believe in the promise of this country, but we’re still waiting.” (One week after our interview, George Floyd was killed by the Minneapolis police.)

This is how Da 5 Bloods came together.

The Rewrite

Da 5 Bloods originated with a 2013 spec script called The Last Tour, by Danny Bilson and Paul De Meo, the writing team behind 1991’s The Rocketeer. Their screenplay was nearly made by Oliver Stone, who developed the project for two years before abandoning it in 2016. A year later, producer Lloyd Levin pitched it to Lee as the director was preparing to shoot BlacKkKlans-man. “Danny and Paul did a great job, but their script was about white vets going back,” says Lee. “So [co-writer] Kevin [Willmott] and I flipped it.”

“There have been good Vietnam films but not one that really dealt with black soldiers’ feelings,” says Willmott, 61, a screenwriter and filmmaker in his own right (2009’s The Only Good Indian, the upcoming The 24th, about the Houston Riot of 1917) who has collaborated with Lee on three consecutive scripts, including BlacKkKlansman, about a black cop who infiltrates the Ku Klux Klan via speakerphone, and 2015’s Chi-Raq, a quasi-musical adaptation of Aristophanes’s Lysistrata in which women organize a sex strike to stop Chicago gang violence.

Lee’s movies with Willmott — which follow disappointments like his 2013 remake of Oldboy and 2014’s Kickstarter-funded vampire romance Da Sweet Blood of Jesus — carry themselves with the confidence of his strongest work, driven by the kind of sharp ideas that critics used to sometimes complain could overpower his storytelling. But amid a culture shift that Lee helped plant the seeds for — and in the wake of blockbusters like Get Out and Parasite, which mix narrative text and sociopolitical subtext at equal levels — not only are Lee’s latest films his best reviewed in over a decade, a few of his older ones are finally getting their due (2000’s Bamboozled, for example, a satire of black representation in entertainment that was initially seen as a misfire, is now considered a masterpiece, with a fancy new Criterion Collection Blu-ray edition to prove it).

Lee credits the success of their partnership to the fact that both he and Willmott are film professors — Lee with NYU’s graduate program and Willmott at the University of Kansas — and have a natural shorthand. Willmott cites their shared belief that “most people get their history from movies, not books, which is not necessarily a good thing — but it may be true, and it makes films like this important.” For research on Bloods, Lee says, he “read every book and watched every documentary” he could find, but he singles out Wallace Terry’s 1984 book, Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Black Veterans, as especially helpful; it was assigned reading for the movie’s actors.

In early 2018, Willmott met Lee at the director’s office in Fort Greene and spent a few days “just going through the original script, marking what we liked and what we didn’t like, and talking through ideas we could add,” says Willmott, who then flew home to Kansas to write a new version. “I typically write the first draft and give it to Spike, who will make changes or give me notes, and it goes back and forth.”

Willmott says he and Lee added the movie’s flashbacks and expanded the role of Boseman’s character, Stormin’ Norman, the Bloods’ woke-ahead-of-his-time squad captain, described by another character as “the best damn soldier that ever lived” and “our Malcolm and our Martin.”

“We based Norman on the black squad leaders that were very rare in Vietnam,” says Willmott. “We wanted to show the pressure they were under, the responsibility they felt toward their men, and the love and reverence their men had for them.” When the Bloods search the shell of a downed plane and discover a chest full of gold bars, originally meant as payment to indigenous fighters assisting the U.S. government, it’s Norman’s idea to reclaim it “for every single black boot that never made it home.” When the Bloods learn about King’s assassination, it’s Norman who persuades them not to turn their weapons on white American soldiers.

If another director had shot The Last Tour with its original script, it would have been “more of an adventure film,” says Willmott. But Da 5 Bloods is a genre-blending, sensory-overload experience on par with Lee’s finest, combining buddy comedy, heist thriller, Expendables-style old-guy action movie, explosively violent war film, and touching drama, all without breaking any seams (albeit spread out over a 156-minute running time). “One of the advantages of working with Spike is that he’s not just writing the script with me; he’s also looking at how he’s going to direct these scenes. He knows how to keep the tone even,” says Willmott. “Plus, he loves to include homages to other movies — when we use film history to our advantage, we can weave in and out of genres without running off the road.”

Da 5 Bloods gives two such nods to Apocalypse Now: On a night out in Ho Chi Minh City, the Bloods visit a bar named after Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film (“That’s a real club!” says Lee), and “Ride of the Valkyries” plays as they reenter the jungle, this time on a slow-moving sightseeing boat. But Lee also acknowledges that the way we think about war movies, even ostensible classics like Apocalypse Now, has changed, especially in their portrayal of the opposing forces. In one of Da 5 Bloods’ flashbacks, Vietcong soldiers cut through jungle brush while discussing their wives and girlfriends back home — right before our so-called heroes gun them down. “The Vietnam War was an immoral war,” says Lee. “I was not going to villainize the Vietcong. How could I do a film like Bamboozled and then make caricatures of the Vietnamese?”

Lee says he hadn’t intended to disrespect any other Vietnam War movies — although in one scene, the Bloods mock ’80s baloney like Rambo and movies like it in which Sylvester Stallone or Chuck Norris engage North Vietnam in fictional rematches under the pretense of rescuing POWs. “They went back and tried to win a war — that they lost — in a movie,” says Lee. “In reality, that shit did not happen.”

Lee and his producers began shopping the script for Da 5 Bloods to studios in late 2018 — but talks heated up in January 2019 after BlacKkKlansman scored six Oscar nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director, and Netflix made the winning bid.

The Cast

To play the Bloods, reuniting after almost 50 years apart, Lee reconvened a few of his own former collaborators: He’d previously directed Lindo in 1992’s Malcolm X, 1994’s Crooklyn, and 1995’s Clockers; Peters in 2012’s Red Hook Summer; and Whitlock in five movies, including BlacKkKlansman and 2002’s 25th Hour. Da 5 Bloods is Lee’s first film with Lewis, a Broadway veteran and longtime friend, as well as Boseman, now one of the biggest stars in Hollywood. But the director’s reasons for hiring relative newcomer Majors, 30, are a mystery, at least to Majors.

“I don’t know what Spike had seen me in — maybe [2019’s] The Last Black Man in San Francisco? It was a casting agent who connected us,” Majors says. “I biked down from Harlem to Brooklyn to meet him at his office. We went to his editing studio, and he showed me a music video he’d made for the Killers dealing with the border wall. And I’m watching it, fool that I am, and I just start crying. And then Spike tells me about the film: ‘Delroy Lindo’s going to play your dad. We shoot in Thailand. You got a passport?’ I go, ‘What? That’s it?’ I walked my bike 14 miles back to Harlem, just kind of like, Holy fuck, and then I called my team: ‘Guys, I got it.’ And they were like, ‘What do you mean you got it?’ ”

Majors’s character, David, wasn’t born until after the Vietnam War, but the actor went to a two-week boot camp in Thailand along with the other actors anyway: “Spike threw me in with the Bloods,” he says. “I was doing the gun training, the formation training. I ripped a lot of pants. I’m 30 to 40 years younger than these other folks, but regardless of age or athletic ability, it was a bitch.”

The Flashbacks

In reality, Lindo is 67, Peters is 68, Whitlock is 65, and Lewis is 56 — but in a gimmick devised by Lee, the actors play their teenage and 20-something selves in war scenes without makeup or The Irishman–style de-aging effects, opposite a frozen-in-time Boseman (whose actual age is 42).

“Here’s the thing,” says Lee. “I knew there was no way in hell I was going to get the budget that Martin Scorsese got [to de-age] De Niro, Pacino, and Pesci in The Irishman, and it was a lot of money. And I dislike when films get different actors to play younger versions of the main characters. Also, makeup or prosthetics would’ve melted in the 100-degree heat.”

But the discount solution provided an effective way to show that the Bloods are still trapped in their wartime memories even as they pass middle age. “It just works,” says Lee. “These guys are going back in time, but this is how they see themselves. We did research screenings, and no one made an issue of it. Hollywood doesn’t give audiences enough credit for their intelligence.”

Flashback scenes were shot on 16-mm. reversal film to mimic newsreel footage from the ’60s and ’70s. “Vietnam was the first war that was really televised, and it was predominantly shot with 16-mm.,” says Da 5 Bloods’ cinematographer, Newton Thomas Sigel. “It’s how the American public perceived the war.” That means the Boseman of Da 5 Bloods, who appears mostly in wartime footage, may look grainier and lower-def than the one audiences recognize from Black Panther and Avengers: Endgame. “I love the irony of shooting the biggest star in the movie in 16-mm.,” says Sigel, “while the rest of the cast was shot with state-of-the-art large-format digital cameras.”

For the more physical battle sequences, Sigel says body doubles were occasionally used, but “those scenes were not designed to be like an Arnold Schwarzenegger film, and the intent was never to disguise the fact that these are gentlemen in their 50s and 60s. Also, some of them are in very good shape. Delroy Lindo swam circles around me in the hotel pool.”

The Production

Production designer Wynn Thomas has worked with Lee on 13 films, including the director’s small-budget debut (1986’s She’s Gotta Have It) and one sweeping, three-and-a-half-hour biopic (1992’s Malcolm X), but he says Da 5 Bloods is something new: “It’s like when David Lean, who had been doing urban British dramas like Great Expectations, made The Bridge on the River Kwai and transitioned into the more epic style we know him for. This is Spike telling a global story, in bigger locations, and shooting them in a very large, cinematic way.”

(Netflix won’t confirm Da 5 Bloods’ budget to me, but producer Jon Kilik, who has worked with Lee on 15 movies, puts it at “somewhere between Malcolm X and Inside Man,” two of the director’s most expensive films, which cost a reported $35 million and $45 million, respectively.)

Da 5 Bloods was shot over three months in 2019 in Ho Chi Minh City and in Bangkok and Chiang Mai in Thailand, where Thomas “walked around for weeks” scouting a variety of jungle locations that become “more claustrophobic as the film progresses. We start the journey in more open areas, so you’re seeing lots of sky and big vistas, and then as the character Paul begins his descent into madness, the trees begin to engulf him — so we go from open and expansive to oppressive and dark.”

Unfortunately, not many cinematically menacing jungles offer drive-through service. “For some of those more densely packed locations, we’d have a base camp at the bottom of the road, and the actors and crew would have to walk a half-hour to get there,” says Thomas.

A bigger challenge was transforming the open field where the older Bloods dig up their gold back into the leafier one where they buried it in 1971. “We shot the modern sequences first and then sent everybody away for ten days,” says Thomas. “We hired a farming community to plant thousands of palm trees and then we brought in the blown-up plane, which was actually built by a Thai construction crew.”

That same local crew spent two months re-creating the ruins of Vietnam’s My Son temples for an action scene near the end of the film. “Obviously we couldn’t shoot the real temples” — which were mostly destroyed by U.S. bombs — “so we had to build our own. We found a space the size of two football fields next to a suburban market, behind a bunch of commercial buildings,” says Thomas. “We did it all out of wood and Styrofoam, but the detail was so intense you could walk right up to the walls and think they were stone.”

The Central Performance

Lee says Lindo was his “first and only choice” to play Paul, the film’s emotional axis, a broken, depressed vet who his fellow Bloods are disappointed to learn has become a MAGA-hatted, build-that-wall Trump supporter.

Lindo himself wasn’t so sure, though. “Spike sent me the script and told me to tell him what I thought,” he says. “But there was that twist — and I did not want to play a Trumpite. So I called Spike and asked if we could just make Paul an archconservative. He thought about it but a few days later said he really needed Paul to be [a Trump voter].”

“I felt it would add some conflict and drama among the group,” says Lee. “We don’t all think alike, and there is a small minority of black folks who drink that orange Kool-Aid.”

So Lindo — who over a 45-year career has been the best part of many films and TV shows, mainly in supporting roles — read the script again and found something to relate to: “I realized Paul was a large, tragic character similar to any of Shakespeare’s or August Wilson’s large, tragic characters: King Lear, or Macbeth, or Herald Loomis in Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. It was clear I needed to play that part. I called Spike back and said, ‘No, man — yeah, I want to play Paul.’ ” So Lindo asked the producers of CBS’s The Good Fight, on which he’s portrayed attorney Adrian Boseman for four seasons, to carve space in his shooting schedule.

On set, “Delroy was avid,” says Lee. “He’s not voting for that guy, but he did what the role required. But as soon as I’d yell cut, he took the hat off.”

Even with his hat on, Paul keeps hold of viewers’ sympathies, a credit to Lindo’s performance — “He’s one of the great underrated actors working today, and I hope this film brings him the acclaim that he deserves,” says Lee — but also the character’s overloaded hard-luck backstory, which features PTSD, money problems, family tragedy, and a strained relationship with his son, among other surprises. How many things does Lee think need to go wrong in a good person’s life to make them vote for Trump? “It could have been one of those or a combination of them all,” he says. “Also, we made this movie B.C. — not Before Christ but Before Corona — and Trump hasn’t helped himself in [dealing with this] pandemic.”

The Release

If not for said pandemic, which has already upended Hollywood’s plans into 2021, Da 5 Bloods would have premiered out of competition at the Cannes Film Festival (where Lee was slated to be the first black jury president in the festival’s history) and played in theaters in May and June — contending with Fast & Furious 9 and Wonder Woman 1984 — before its global debut on Netflix. But with all other would-be blockbusters stuck in limbo until multiplexes reopen, Bloods could be this summer’s biggest release. “If there is any silver lining” to the lack of competition, says Majors, “it’s that we get to bring the story of some actual real-life heroes to everybody’s homes.”

“It’s weird for everybody, but we made adjustments,” says Lee (who, even in quarantine, is making work that speaks to the present moment; in the past month, he’s released two short films, a mini-documentary about New York under lockdown and another called 3 Brothers—Radio Raheem, Eric Garner, and George Floyd, which intercuts footage of the deaths of Garner and Floyd at the hands of police with that of Bill Nunn’s character from 1989’s Do the Right Thing). Pre-coronavirus, the director was able to hold four screenings of Da 5 Bloods for black Vietnam vets. “That was the real validation for this film. They all gave me a hug and said, ‘Spike, we saw your World War II movie and thought, What about us? We were waiting on your ass to do this film.’ ”

Da 5 Bloods will premiere June 12 on Netflix.

*A version of this article appears in the June 8, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!