This week, Stephen King releases his latest novel, Mr. Mercedes. It is his 65th book, if you count novels, nonfiction, and short-story collections, and we are using its publication as an excuse to look back over nearly 40 years’ worth of his work and make the tough, ruthless calls to rank them all — no cop-out ties allowed. (Note: Mr. Mercedes is not included in this ranking.)

64. Rose Madder: In the early nineties, King wrote a set of novels focused on abused women and the horrible men who beat and haunt and entrap them. This one was the last and least of the bunch. The combination of the real (the title character, the battered women’s shelter she ends up with, her monster of a husband) with the supernatural (a magical painting that offers a gateway to a Greek myth-tinged world) feels less convincing here than it does in any other of King’s books.

63. The Tommyknockers: This tale of a Maine writer (you’ll be seeing a lot of these) who accidentally comes across a piece of alien metal in her backyard and finds herself compelled to dig up the flying saucer that it’s attached to was written at the height of King’s addiction troubles. Writing with “his heart running at a hundred and thirty beats a minute and cotton swabs stuck up my nose to stem the coke-induced bleeding” (as he would later describe it), King filled his book with addicts and thinly veiled metaphors for what he was going through. Full of anger at himself and the eighties, The Tommyknockers is a white-hot mess. Anyone who remembers the deadly levitating Coke machine would agree.

62. Dreamcatcher: King’s first novel released after the 1999 car accident that nearly killed him, Dreamcatcher is so body-obsessed as to be off-putting. Though the descriptions of the pain and suffering felt by the main character (who suffers a similarly crippling accident) are convincing for obvious reasons, the book’s “shit weasels” — which literally make their way out of human bodies by getting crapped out — are the lowest type of gross-out horror. The only thing worse is the clichéd Down syndrome–afflicted character with the telepathic powers.

61. Insomnia: Unless you are familiar with King’s epic Dark Tower series, entire swaths of this gargantuan novel are unreadable. Though the sections dealing with the elderly protagonist and his lady love have a poignance to them, they are undercut by heavy-handed subplots about spousal abuse and the pro-choice/pro-life debate.

60. The Regulators: In 1996, King released two books simultaneously — one under his own name and one under his retired pseudonym, Richard Bachman. Meant to be carnival mirror reflections of each other, the two books feature many of the same characters, though with different motivations and circumstances in each. This one, the Bachman book, tells the story of a small-town street that is beset by two vans full of gun-wielding murderers. That description makes the book sound more coherent than it actually is — as the bad guys have been summoned by the mind of a TV-obsessed autistic boy possessed by an alien being. It’s like that Twilight Zone episode where the little boy turns one guy into a jack-in-the-box, but more with people getting their heads blown off.

59. Rage: Originally published as a Bachman book, this was actually the first full-length novel that King ever finished. Concerned with a high-school student who kills two teachers and takes over a classroom, the story is very much the work of an angry young man — overheated and full of big talk. Wisely or not, King allowed the book to go out of print, partly because of a fear of having future school shootings linked to it.

58. The Dark Tower VI: Song of Susannah: Taking place over the span of a single day, the sixth entry in King’s Dark Tower opus is its most minor. Blame its place in the series (the relatively slim book serves mainly as a transition volume between two thick volumes) or its mind-boggling metafictional flourish. Either way, it it an odd fit with everything that preceded it.

57. Blaze: Originally written right before Carrie, but kept in King’s trunk until 2007, when he published it under the Bachman name, Blaze is a wisp of a tale. A noir-light about a brain-damaged crook who steals a rich man’s child in order to ransom it off before he finds himself getting too attached, it thankfully stops two steps short of over-sentimentality. Yet there’s almost nothing memorable about the story other than the ways in which it reminded us of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

56. Gerald’s Game: The first in King’s early nineties feminist cycle, Gerald’s Game takes place almost entirely in one room, with one character. Handcuffed to her cabin bed after her husband dies in the middle of a naughty sex game, Jessie must somehow find a way to escape. The one-room, one-woman setting allows King to overindulge in one of his most recognizable (and sometimes frustrating) tics: the character who speaks out loud to themselves for no good reason. Though the supernatural is absent from this novel (as it is in many of his books, despite King’s reputation), there remains in this novel one of the author’s scariest reveals.

55. Cell: After a pulse of some sort turns everyone who is talking on their cell phones into murderous zombies, the survivors (all of whom turn out to be sarcastic smart-asses) walk around and speak in ways that no one in a zombie apocalypse ever would. Though it delivers some great setpieces, it also contains the worst dialogue King’s ever written.

54. Blockade Billy: “The game was played hard in those days … with plenty of fuck-you.” Apparently, baseball used to be a rough sport. This novella is a trifle, but King writes lovingly about his favorite game.

53. Cycle of the Werewolf: Originally intended to be twelve vignette-length segments, each of which would run alongside an illustration in a calendar, Werewolf sees King regress to cheesy, gory prose reminiscent of the beloved EC Comics of his youth.

52. The Colorado Kid: A slim addition to the fun Hard Case Crime series of books, this tale of a young newspaper reporter, her two crochety editors, and the mysterious story they unspool has angered many readers with its deliberate lack of closure. But, as King writes, “Wanting might be better than knowing.”

51. Black House: Released the week of September 11, this sequel to 1984’s King/Peter Straub co-written novel The Talisman picks up the story of Jack Sawyer who, when younger, traveled to a parallel world called the Territories. As with Insomnia, there are chunks of Black House undecipherable to the Dark Tower uninitiated. Yet there is both an authorly tension and bond between King and Straub that results in more lovely passages than the typical lesser King book has any right to offer.

50. Needful Things: King’s “Last Castle Rock Story” (the fictional locale was the setting for The Dead Zone, Cujo, and The Dark Half) sees a man named Leland Gaunt roll into town to open the titular curiosity shop. It’s the type of place you can get anything you want — for a price. Partially a satirical look at Reagan-era American materalism, the book plays broader than it should, but less funny than King (who considers the book a black comedy) would have liked.

49. Christine: “Kids are a downtrodden class.” In the early part of his career, King wrote thousands of pages on this very point. But when it comes to kids and outcasts and the dangers of adolescence, Christine — about a killer car that entrances the mind of a high-school loser — just skims the surface of those most transformative years. Future kid-centered books would be both scarier and deeper.

48. Duma Key: Another attempt at hashing out the lingering effects of his car accident on the page, Duma Key finds King writing about a non-writer artist for the first time. Edgar loses his arm in a construction accident but gains the ability to make things happen when he paints them. Set in Florida, where King now lives for much of the year, Duma Key locates the (non-political) horrors of that fecund, overgrown state. But the novel, like many of King’s later works, could have used judicious pruning.

47. The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon: As many characters on HBO’s Game of Thrones like to say, “The night is dark, and full of terrors.” But, and this bears repeating, when it comes to King, the terrors are not always monsters. Sometimes they’re men. And sometimes, it’s nature, as in this tiny realist portrait of a 9-year old girl who gets lost in the woods. As she wanders, afraid and alone, the only thing to keep her company is her radio, broadcasting a Red Sox game featuring her favorite player. It’s a simple story about a simple lesson: “The world had teeth and it could bite you with them anytime it wanted.”

46. Four Past Midnight: A collection of four novellas that contains both one of King’s most ingenious situations (in The Langoliers, a group of plane passengers slip through a crack in time to a few minutes before, where the monsters reponsible for eating the past exist) and one of his most unreadable stories (The Library Policeman, which mixes childhood trauma and supernatural horror in a most unsatisfying way).

45. Firestarter: King is in full on “paranoid dude of the sixties-seventies mode” here. The Shop is a secret government agency that, on account of an experiment it performs on one college campus, inadvertantly creates two students with special powers. They marry and have a kid who is capable of wreaking fantastic havoc through her psychic control of fire. With several wonderfully tense set pieces, the book nonetheless has a few too many stationary scenes set in an underground government bunker.

44. Joyland: King’s second book for the pulp retro publisher Hard Case Crime (the first was #52, The Colorado Kid), Joyland is a small tale about a boy who goes to work in a rundown theme park in North Carolina and becomes a man. It’s a sweet coming-of-age story with a slight mystery lightly wrapped around it, as well as some minor supernatural doings, but at this point, those feel like reflexive tics on King’s part more than anything else. The thing that comes through most in slim books like this, Colorado Kid, and The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon is how quickly and efficiently King can write a character that feels like someone we’ve long known.

43. Nightmares & Dreamscapes: His third short story collection, this book’s a beast, big and baggy. But there’s enough of a mix of the surreal (the story with the human finger sticking out of a drain), the silly (the haunted toilet stall) and the scary (the Lovecraftian “Crouch End”) to prop up the lesser tales.

42. The Running Man: Another angry Bachman book, another plot about a dystopian game show. But this one’s a slam-bang action-suspense story (supposedly written over the course of anywhere from three days to a week), in which one man must evade a group of well-supplied hunters out to kill him on live TV. The novel (spoiler alert!) ends with our hero flying a jet into a skyscraper. Like Tom Clancy’s Debt of Honor, in which an embittered pilot flies a passenger jet into the U.S. Capitol, it is hard to read the climax of The Running Man without dredging up the obvious associations.

41. Faithful: It’s hard to fully enjoy this book if you’re not a baseball fan (and more specifically, if you’re not a Red Sox fan). Co-written by King and novelist Stewart O’Nan, it follows the two of them through the 2004 season, when the Sox miraculously and finally won their first World Series in 86 years. For those who aren’t fans, it gives readers this insight into the depth of King’s reading obsession: “Baseball is a great game because you can multitask in so many ways and never miss a single pitch. I find I can read two pages of a book during each commercial break.”

40. Just After Sunset: This 2008 collection was a reminder that King is the only best-selling popular novelist who still regularly traffics in the short-story form. One of the book’s longer stories (“N”) is classic cosmic horror in the vein of Arthur Machen (directly) and H.P. Lovecraft (indirectly). “The Cat From Hell” and “A Very Tight Place” are both the right kinds of gory-nasty, while “They Things They Left Behind” subtly deals with 9/11 survivor’s guilt. A solid late career addition.

39. The Dark Tower V: Wolves of the Calla: The Dark Tower series has always been a genre mash-up, but it was only in Wolves of the Calla that readers first realized how all-encompassing King was going to be in his vision. A loose rewriting of The Magnificent Seven, Calla also manages to throw in significant references to Star Wars, Harry Potter, and Marvel Comics. The climactic confrontation is a prime example of what King does not do well — battle scenes. Hundreds of pages of dialogue and it’s all over in seconds. Sure, that’s how gun battles typically go down, we reckon, but give us a little more, man!

38. Bag of Bones: “Readers have a loyalty that cannot be matched anywhere else in the creative arts,” says Mike Noonan, the Stephen King stand-in and protagonist of Bag of Bones. “Which explains why so many writers who have run out of gas can keep coasting anyway, propelled onto the bestseller lists by the magic words Author of on the covers of their books.” King has yet to run out of gas, and critics have responded — since the turn of the century, he has experienced increasingly positive notices for his novels. This book was the turning point, pushed by new publisher Scribner (of Fitzgerald and Hemingway fame) as a piece of literary, rather than genre, fiction. Still, it’s not nearly as good as the critics thought, full of King standards (a Maine writer, a dead family member, the past resurfacing, puzzles to be solved) that have trouble convincing us that they are anything but the same old.

37. Everything’s Eventual: Another short-story collection, this one features four King tales that made it into The New Yorker, including “That Feeling, You Can Only Say What It Is in French” (is that a New Yorker title, or what?) and “The Man in the Black Suit,” which won King an O. Henry award in 1995. The book was published in 2002, right as the critical shift toward King had approached one of its peaks (the following year, he would receive a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Foundation). Still, for all their literary merit, few of the stories stick in your nerve centers.

36. The Dark Tower: The Wind Through the Keyhole: Or, Dark Tower 4.5, as King is calling his latest release. Set in between the events of Wizard and Glass and Wolves of the Calla, Keyhole contains a story within a story, a fairy tale of great adventure and beauty. Because of its interstitial position, though, the book cannot wholly live on its own.

35. Desperation: If The Regulators (No. 60) is about TV, Stephen King once said, then Desperation is about God. The second half of the Bachman-King double feature finds the Lord channeled through a young boy, one who is forced to become a religious leader of sorts for a group of people trapped in a small desert town and hunted by a demon-posessed sheriff. It’s a book that manages to balance scenes of complete gross-out horror with tiny moments of grace.

34. Thinner: He should have just published it under his own name, it was so familiar and Stephen King–ish. But Thinner, with its supernatural plot of an obese lawyer who starts to lose weight, unceasingly, after a gypsy curses him, was released under King’s pseudonym, Richard Bachman. With four books to his credit, Bachman had never written a story with anything approaching the otherworldly, which tipped some off that King and Bachman might be the same. A harsh look at American success and excess and avarice, Thinner takes a Tales From the Crypt conceit and spins it into something lean and mean.

33. Full Dark, No Stars: The four novellas in this collection are all tales of revenge. They’re bleak as hell and that’s what makes them so good (though not even close to the four novellas in Different Seasons, which we’ll talk about later). The quartet’s unyielding darkness appeared to be King pushing back a little against his late-career critical bump. “I have no quarrel with literary fiction, which usually concerns itself with extraordinary people in ordinary situations,” he wrote. “But as both a reader and a writer, I’m much more interested by ordinary people in extraordinary situations. I want to provoke an emotional, even visceral, reaction in my readers. Making them think as they read is not my deal.”

32. The Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: It is in this third volume of his magnum opus that King truly begins to give us a sense of the world he has created — in actuality, it’s many worlds. A multiverse, in the most comic-book sense of the word: The Dark Tower of the title is the thing that holds all realities, all worlds together. Demerits for the puzzle-happy talking train that arrives at book’s end, but points galore for setting the stakes as high as possible for his heroes.

31. The Long Walk: This Bachman book imagines a dystopian United States where 100 young men are forced to participate in a death march through Maine. The winner is lavished with anything he wants. The whole thing is televised, and the nation watches with sick glee. Each chapter opens with a quote from a game show, but the most germane is one from The Gong Show’s Chuck Barris: “The ultimate game show would be one where the losing contestant was killed.” The Hunger Games before The Hunger Games, but with a world-weary, Vietnam-draft metaphor to boot.

30. Cujo: Thirty years later, the name still serves as shorthand for a vicious dog. And it’s a vicious book (that ending!), one that even manages to take us, if briefly, into the point of view of a rabid pooch. It was King’s first explicitly non-supernatural book (there are some hints here and there, but it’s mostly rabies and human weakness to blame) and so is important, though it is firmly of middle quality.

29. The Dark Half: “Pseudonyms were only a higher form of fictional character,” writes King in this 1989 novel. Taking the circumstances surrounding the unmasking of Richard Bachman and poking them with a stick, he imagines a pen name that won’t stay dead. In between all the messy razor killings and flocks of ominous sparrows are a great many passages that reveal the inner mind of the fiction writer — he who exists in two different realities at the same time, “The one in the real world and the one in the manuscript world.”

28. The Eyes of the Dragon: A fairy tale written by King for his daughter Naomi. Granted, it’s a long fairy tale, but it’s perfect in tone and the obvious signifiers — dragons, towers, kings, and princes.

27. Doctor Sleep: King had been in this situation before — he released a sequel for one of his many young characters with 2001’s Black House. The difference here is that this time around, he was dealing with one of his most famous books and characters. (Partly made so by the Stanley Kubrick movie version that King has spent over three decades insulting.) The expectations were high, and it’s amazing that King didn’t completely whiff. How much Doctor Sleep succeeds depends on your desire to re-create the frights of The Shining, which are largely absent here. King knows as much — on the press tour, he’s said that his current work is more like a curve or change-up than a fastball. (The man loves baseball!) Danny Torrance is all grown up now, and like his old man Jack he likes to drink. He ends up in AA, of which the book and its AA-attending author have much to say, and crosses paths with an evil group called the True Knot, who get their power from killing kids with the shining. The book flies, but misses that Shining punch, leading to a conclusion in which the villains, as is often the case in King books, turn out to be less dangerous than they seem.

26. The Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: Bloated to a certain degree, the book also falls flat when it finally unveils the villain who has loomed so large over the series. But the saga’s conclusion also contains one of the most honestly tear-jerking scenes in all of King’s work. And though there are many who fall on either side of this debate, we consider the book’s final ending to be satisfying in a way we didn’t think possible.

25. Carrie: The first novel, the breakthrough, the book that kicked off one of American fiction’s most successful and long-lasting careers. All of that is true. But the thing itself — book as text, not context — often feels like a screenplay outline padded out by faux-newspaper and academic journal reports.

24. 11/22/63: It is a liberal boomer’s historical fantasy, a re-litigating of King’s younger years — go back in time and prevent John F. Kennedy from getting assassinated and prevent Vietnam, man. The JFK assassination (and to a lesser extent, the 1966 Charles Whitman sniper shooting) has popped up again and again in King’s work. As he writes in his memoir/writing manual On Writing, “Ever since John F. Kennedy was shot in Dallas, the great American bogeyman has been the guy with the rifle in a high place.” So it’s not surprising that he would focus an entire book on the event. It’s a very good historical novel, full of convincing era details and fond affection for sixties America. As often happens with King, the book turns into a small-town portrait for a time before delivering an honest-to-God suspenseful third act.

23. The Green Mile: Taking after Charles Dickens, King decided to try to release a serial novel, in six parts. The challenge? Keep them coming out at regular intervals, have a cliff-hanger at the end of each mini-book, and maintain quality control along the way. He succeeded, and all six books (taken here as one novel) are full of humor and heart. The climax is heartrending, if obvious. “Not long after I began The Green Mile and realized my character was an innocent man likely to be executed for the crime of another, I decided to give him the initials J.C.,” wrote King. “A few critics accused me of being symbolically simplistic … And I’m like, ‘What is this, rocket science? I mean, come on, guys.’

22. Hearts in Atlantis: King hasn’t been so successful because he writes well about scary things. No, he’s been so successful because, in addition to that, he also writes about the American Boomer middle class. This volume strings the specter and consequences of the Vietnam War — that generation’s great conflict and shame — throughout a series of interconnected novellas and short stories. “You lost your innocence when you grew up, everyone knew that,” says one character. “But did you have to lose your hope as well?”

21. Night Shift: King’s first collection of short stories, released in 1978, is packed with satisfying, pulpy tales like “The Boogeyman” (which has an incredible shocker of an ending), “Gray Matter” (about, seriously, an alien beer that mutates a man) and both a prequel and sequel to ’Salem’s Lot.

20. Roadwork: “Stephen King has always understood that the good guys don’t always win, but he also understands that mostly they do,” writes King in his essay “The Importance of Being Bachman.” Basically, King generally likes to end his novels on an up note, and Bachman, the opposite. Those endings are dark. Take this book, in which a city decides to build a new highway that will require the destruction of one man’s job and home. He decides to fight back, in his own little way, but as we all know, bureaucracies can be the scariest kind of monsters — unyielding, single-minded, and unfeeling.

19. The Dark Tower II: The Drawing of the Three: The “drawing” of the title refers not to an artist’s sketch, but rather the picking, as if from a deck of cards, of three people to accompany the hero on his multi-book journey to the Dark Tower. There is incident to spare, but King focuses primarily on sketching out character — he seems to know that he’s going to be with these people for years to come and wants to figure them out along with us.

18. The Talisman: There is a beautiful little passage late in this book in which its main character, Jack Sawyer, looks into a magical object and sees glimpses of other worlds all at once. It’s a moment indicative of the story’s expansiveness. Written by King and friend Peter Straub, The Talisman is a good old sprawling adventure epic: a young man must make his away across two worlds (one Tolkein-esque) in order to save his dying mother. With classic villains and heroes, comic relief and moments of savagery, it’s worth revisiting in these fantasy-obsessed times.

17. Dolores Claiborne: Impressive as both an exercise in form and voice, this 1993 novel is one long monologue. No chapters. Just one long story as told by the title character, who is being interrogated in the death of the old lady who employed her as a housekeeper. Underrated on account of its slow, unspooling plot, it’s nonetheless one of the more impressive things King’s ever written.

16: From a Buick 8: Speaking of underrated, this late career tale of a mysterious car whose trunk leads into another dimension contains some of King’s most hard to shake descriptions of things from the unknown. Along with The Colorado Kid, Buick 8 also tries to argue that good stories don’t always have satisfying endings. Such a thing is a “childish insistence.”

15. Pet Sematary: “Death was, except for childbirth, the most natural thing in the world,” says the doctor at the center of this book. Still, there is never anything natural about the way death is handled in King’s novels, and this might be the most death-obsessed of the bunch. When a doctor discovers an ancient Indian burial ground, he starts to put dead things there (his cat, his son). They don’t stay dead for long. Parents, all too aware of the fragility of their young children, might find this book scariest of all.

14. The Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: The book that kicked off the entire saga contains one of King’s most evocative sentences. It also happens to be the first line: “The man in black fled across the desert and the gunslinger followed.” A mash-up of Western, fantasy, and horror, The Gunslinger features some of King’s straight-up weirdest scenes — witness the moment when a man is brought back from the dead. That one will stick around for a long time.

13. Skeleton Crew: King’s second short-story collection shows a range that most authors of any genre would be incapable of achieving. There’s the requisite gross-out tale (“Survivor Type,” in which a man marooned on a desert isle starts to eat himself bit by bit), an ambitious novella (The Mist), and a sweet piece about an old lady and the way in which she decides to leave this world (“The Reach”). Dude even throws two poems in for good measure.

12. Under the Dome: A pulp concept (one day an invisible dome appears around a small Maine town, trapping everyone inside and keeping all others out) complicated by a boatload of modern-day concerns — Iraq, waterboarding, Katrina, Obama, Bush, meth, the environment, the far-right. An ambitious work and one of the author’s most political books.

11. Lisey’s Story: A novel unlike any other in the King catalogue. It is a terrifying leap of imagination for King — the story concerns the widow of a famous writer. And yes, there’s some otherworldly stuff that goes on here, but the book is most concerned with the secret language that develops in any long relationship. Full of memories and flashback and internal dialogue and exhortations shouted out to empty rooms, this is one book that’ll never be made into a crappy movie.

10. Danse Macabre: An early eighties nonfiction work in which King dissects the many forms of scary books and movies. A dense read, it is nonetheless catnip for anyone who has ever cared a whit about horror.

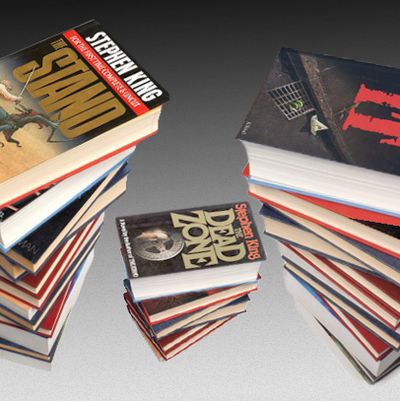

9. The Dead Zone: This book about a man cursed with the ability to see the future is many things — a psychic chiller, a serial-killer novel, a political thriller — but what lingers the most is the main character, Johnny Smith. There is a sense of melancholy around him that cannot be found elsewhere in the King universe.

8. ’Salem’s Lot: It remains one of the best vampire books ever written. An update of Dracula (bloodsucker arrives in town from abroad, wreaks havoc) crossed with the small-town drama of Peyton Place, ’Salem’s Lot showed that the fears and myths of the fusty past could easily exist in the modern wor

7. The Dark Tower IV: Wizard and Glass: This prequel tells the story of a young Roland, his first great adventure and his first (possibly only) true romance. It’s an incredibly well-told tale, one that aches with a sense of young love other authors could only fantasize about writing.

6. Misery: Originally meant to be a Bachman book, with all the darkness those books are known for, this tight thriller somehow makes a popular writer’s greatest fear (getting kidnapped by an insane fan) our greatest fear, if only temporarily. Annie Wilkes, writer Paul Sheldon’s “number-one fan,” is one of King’s most hilarious, batshit crazy creations.

5. Different Seasons: Four novellas: Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption, Apt Pupil, The Body, The Breathing Method. Three of them are utter knockouts. (Not coincidentally, all three of those were made into good to great films — you know The Body as Stand by Me.) There’s not a ghost or demon in the bunch, just great characters and frightening portraits of humanity.

4. The Shining: If ‘Salem’s Lot is the great modern vampire novel, then The Shining is the great modern haunted house book. It may be a while since you’ve read it, and the name may conjure up only the images from Stanley Kubrick’s film, so iconic are they. But drip into it again and you’ll see why the book holds up. In addition to being one of his most frightening (the lady in Room 217!!), it’s also one of King’s most personal works — the story of an alcoholic writer and the havoc he wreaks upon his small family.

3. IT: One of King’s biggest books, both literally and figuratively. He throws everything he’s got in this one. Concerned with a group of kids who have to fight off an evil, alien child killer, IT is about the essence of fear, the mysterious nature of small towns, the 1950s and movie monsters. King’s wisest book about the dangers and joys of childhood (of which he wrote much in his early years), it also contains more scares per chapter than anything he wrote before or since.

2. On Writing: These days, it seems as if there are more people writing than ever before. Self published e-books, blogs, Twitter, Facebook — from long to short, everyone fancies themselves a writer with something to say. Which is why King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is so essential. The first half of the book is a mini-memoir, evocative, funny and matter of fact (“I was built with a love of the night and the uniquet coffin, that’s all. If you disapprove, I can only shrug my shoulders. It’s what I have.”). The second half is a writing manual (a new Strunk and White of sorts) that is practical as hell. It goes through the tools that all writers must effectively employ — vocabulary, grammar, narration, description, dialogue, character, pace, themes — and offers one absolutely essential lesson: “If you don’t have the time to read, you don’t have the time or the tools to write.” Make the time to read this one.

1. The Stand: One might think it amazing that Stephen King’s tale of a superflu that wipes out 99 percent of the United States still looms so large over all other post-apocalyptic works, so often have the subgenre’s tropes been used in fiction and film. But the author’s sprawling work (which he expanded by 400 pages in an edition released a dozen years after his original) operates on the grandest of scales, literally a battle between good and evil, between God and something like the Devil. The book’s heroes, villains and individual moments are so well written that they remain some of the more memorable in all of late 20th century popular fiction. And while King has said, “There’s something a little depressing about such a united opinion that you did your best work twenty years ago,” we have trouble being down on something so great.