The plot twist was preordained from the first episode of the series, and even built into the title: At some point, surely, Waystar Royco’s cruel and ruthless patriarch would die on Succession. But even the most studious fans of the HBO series didn’t expect him to perish in episode three of the show’s fourth and last season. The innocuous title, “Connor’s Wedding,” led viewers to expect another variant of one of the show’s recurring, always crowd-pleasing set pieces: a family gathering that becomes a black hole of ill will. They did not anticipate a wedding episode that would become a death episode, finally forcing succession on Succession.

Unfolding more or less in real time, “Connor’s Wedding” alternates party scenes on a yacht where the eldest Roy sibling, Connor (Alan Ruck), prepares to marry his reluctant fiancée, Willa (Justine Lupe), with frantic backstage communications between the other Roy siblings and the company executives on a private jet where Logan has collapsed. Mark Mylod, who has honed the anxious, tactically ragged visuals that underscore the Roy empire’s instability by directing of 13 of the series’ 32 episodes, put an already tense and consequential story into a production vise by documenting nearly half the drama on the yacht in one continuous, unbroken take. Using multiple 35-mm. film cameras with magazines that could hold a maximum of ten minutes of footage before reloading, Succession’s “documentary” aesthetic became more than a conceit, resulting in a filmed record of actors performing some of the most emotionally and logistically taxing work of their lives and a camera crew capturing it all while remaining invisible.

How did you decide to kill off Logan and, specifically, have it happen halfway through episode three of the final season?

The original intention was to kill off Logan in season one, but it quickly became apparent that the dramatic conflict between Brian and the kids was so strong — in that lovely Darwinian way that television can evolve in a series — that there was so much to mine from. So the character stayed alive.

Around the beginning of production on season three, Jesse spoke about this idea that, probably in the beginning of season four, the character of Logan should die and we’d have a paradigm shift in the way we told our story. He spoke of this idea of, “What if it was the least dramatic, most mundane, most inconvenient death, really, in the way that sudden death in our age tends to happen? It’s a phone call, a text message. There’s a confusion.”

And in that mundanity — from the uncertainty that comes from having two parties, one on a plane and one stuck on a boat, with just a phone-call connection between them — what felt like it would be really interesting, if it happened early in the episode, was the tension that goes with the uncertainty that immediately follows the news. That seeking of relief, of clarity, and it never happens.

So the principal locations of a plane and a boat were selected after the decision was made to create a scenario where the siblings had a hard time getting information and communicating?

Exactly. The first instinct was to say, “Let’s have it happen early in the episode, and early in the season” — in a place where, within television grammar, it would seem least likely to be expected.

The scenes on the boat, the chain of information, the literal game of telephone that occurs: How did you shoot that? Is it true that you devised a way to film it in one continuous burst, like a three-dimensional stage play?

Yes, that’s exactly right. Because we shoot on film, we need to reload every ten minutes because the camera roll runs out. But there was this one particular section right after the intense news comes in, when Kendall walks outside and speaks to Frank and gets confirmation, where it felt like it needed to be an unbroken performance. That’s just the way we work — we needed to look at the actors continuously for that half-hour, or I needed to. There’s a whole subsequent post-production editing process that goes into it, but we typically shoot with two cameras, and it felt almost frustrating to have to break that sequence up. Having shot it in eight-page increments, I spoke to the production team and the cast and said, “Can we work out a way to do it all in one?”

So we did. We gave the actors some prep time, and cinematographer Patrick Capone worked with the operators, and we hid magazines and reloads and camera bodies around the set that they could pick up so that one camera could be running at all times. And then we went for it for a 28- or 29-minute take.

So if I were to Zapruder this entire episode, might I spot a camera operator or a film magazine or camera body hidden behind a door frame or an item of furniture?

I hope we got them all out! We’ve gotten pretty good at shooting this way. There’s a lovely dance that we do on the show, the messy choreography between the actors and camera operators. This was taking it to a new level, doing it over a nearly half-hour period. Everybody rose to the occasion, and it felt like the right thing to do. The results we got in terms of the intensity and flow of performance back that up. Afterward, we all felt both exhausted and like we’d gotten something really great in the can.

Much of the episode is shot on the boat where Connor’s wedding is supposed to take place. You have all of these people playing extras. They all have phones. Even if you make them sign NDAs, there still might be people texting their friends to coyly say, “I’m filming an episode of Succession, I’m on a boat, and a really big event is happening!” How do you control the flow of information?

In retrospect, I consider it damn near miraculous that we got this done without a big exposé. I’m massively grateful to HBO security for giving us good advice on how to set up our store when we were shooting not just this episode but subsequent episodes throughout the season. And mainly, I suppose, I’m grateful to the 250 extras that we had on that boat for a week or two, because they could have said something and they didn’t.

The extras knew?

Yeah. Even if they didn’t know explicitly — the hard, very explicit dialogue was happening in a separate room — it wouldn’t have been difficult to glean from the atmosphere on set. As you say, NDAs — there are ways you can get around those, I’m sure. We spoke to the extras and asked them for their cooperation, and on that occasion as well as on subsequent episodes, everybody kept themselves zipped.

All the scenes on the plane where they’re trying to revive Logan and talking about drafting the memo in the event of his death — was that all done on a soundstage?

We shoot the interior of the plane on a soundstage. When it became obvious in season one or two that we would be spending a lot of time on WayStar jets, we built a fuselage on a soundstage in Queens with green screens outside of the windows so that we could add skies in post-production. We shot all the aircraft fuselage stuff for this episode after the scenes on the boat, the intention being that we would need to see very little of it because so much would be conveyed by hearing Tom over the phones used by the characters on the boat.

But Matthew’s performance ended up being so strong that we used a load more of that than we had intended. He was just so damned good, so compelling, that it was difficult not to keep cutting to him.

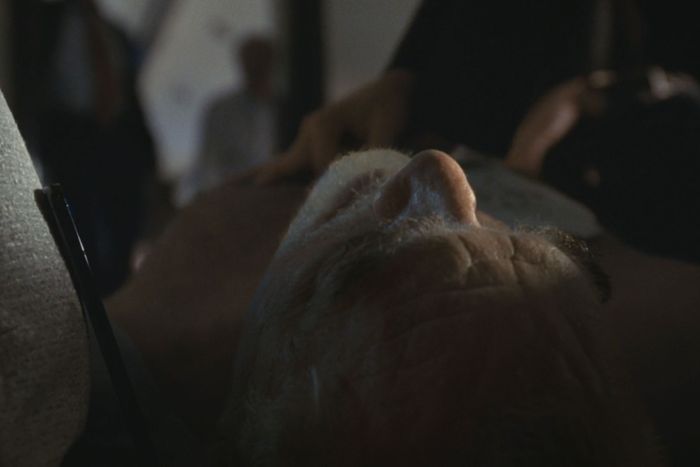

Can you walk me through the visual calculus of what information to give the audience about Logan’s medical episode? Am I correct that you only get a good look at his body being worked on once?

That’s correct. We saw a little glimpse of it earlier, but there’s only one shot where you see his face. That was based on instinct on my part. The idea of putting the camera on a prostrate Logan felt disrespectful to me, instinctively. Humbling, we are all mortal, et cetera. I talked to Jesse about this, and he had the same instinct. Generally if we both agree on something, that’s a good way forward. So we avoided showing his full face, except at what felt like a very deliberate and necessary time where we needed to make a connection with Sarah’s character: the kind of pathetic folly of her speaking to this character who is having these heart compressions and is fairly obviously dead, and yet she’s still speaking to him in this heartrending way. We needed to see the phone held up against his ear, and his face, at that time. But that was the only time where I thought I could ethically or dramatically justify it.

It’s interesting that you are so cognizant of preserving the dignity of this horrible patriarch of a horrible family!

Throughout four seasons of this show, I have found myself being this horrible enabler of the characters’ bad behavior, yet also protecting them and caring for them, trying to look out for them. It’s this odd Stockholm syndrome.

How did Brian Cox react when you told him, “We’re killing Logan in episode three of season four?”

It was very sad. Jesse, once we were sure that’s what we had to do, took Brian out for lunch. I shouldn’t speak about events for which I wasn’t present, but they’re both friends, so I’ll say that it was a sad conversation. Obviously someone of Brian’s experience took it very well. But he was sad. And it took him a long while to come to grips with it. This was a long period of our lives in terms of duration and intensity.

What sorts of conversations did you have with the principal cast members about how to portray all the stages of the crisis?

The script was a great pathway, so vividly written, that that was our map. In terms of finding the tone of performance: There’s a mutual respect and understanding with the cast here that’s so rare in terms of working relationships. So much goes unsaid. I sat around and talked with the cast. I talked about losing my mum.

But ultimately I rely so much on the actors’ first instincts and then we calibrate from there. I don’t like to talk too much before we go. This sounds almost anti-directing sometimes! But in the case of that scene where they first find out, I was deliberately vague with everybody: “Okay, could you walk in there? That zone is good, that zone is good, that zone is bad.” At some point, “Could you go downstairs and find Sarah? She should be somewhere in the main room. Sarah, look out for this emotion, this piece.” I’ll give them things to sniff for. But I’ll be oddly vague in the first take, and we’ve come to trust that.

What’s the goal?

What that gives us, as storytellers, is a sense of barely keeping up with events; i.e. not anticipating them remotely. That can be in the way the camera has to find stuff without anticipating, or in the timing of a cut to somebody speaking. You’ll see that we often try to cut slightly late, or have the camera pan slightly late, so it’s not like we’re anticipating. Cumulatively, hopefully, there is that rhythm of, “Yeah, we’re just trying to keep up,” and never quite being on top of it. Which is quite literally, in the experience of our characters, a sense of trying to control that which cannot be controlled. In this case, trying to control the death of their father, which they cannot. And trying to control the flow of information, which again, they cannot.

It’s interesting how the micro of all the production techniques the show has developed became the macro in “Connor’s Wedding.”

It was the perfect manifestation of it in this episode.

You mentioned the death of your mother in passing earlier. If it’s not too personal, could you tell me what parts of that experience you were able to bring to bear here?

The conversation I was having with close friends about that experience was about two things: One, how the emotion hijacks you at completely surprising and unexpected times. The other is the way in which grief or shock sometimes manifests itself as oddly comic. Random.

Alan Ruck, I thought, was an absolute master of showing that in the scene where Connor has to be told of his father’s death. The way that Alan played the abruptness of that, the stripping away of any kind of bullshit and going into a place of absolutely, almost aggressively blank honesty felt completely true to me from my own experience. Most of us have gone through some kind of grief over a family member. It’s rarely like it is in the movies. It’s really odd. I suppose it was all about giving ourselves permission to play it that way, instead of settling into a kind of trope.

There’s a saying that you can’t unring a bell. But of course, TV shows find ways to do it all the time — sometimes convincingly, sometimes ludicrously. But here, you have quite a lot of bells that simply cannot be unrung. The patriarch is dead. The siblings are on the outside of the corporation looking in, and you can already see that the people inside are circling the wagons. Could you go for another season?

I suppose we could. Going into season four, we wanted to change the paradigm of our dramatic conflict from the siblings to the father — those machinations of changing sides — to swing the conflict in a different direction. That was what was really behind the choice of Logan dying at this point in the season. Could we go for a season five? Of course we could. We’ve got brilliant actors and brilliant writers. But it doesn’t seem like the right thing to do, does it? We’re just finishing post-production on the last couple of episodes now. I don’t think we could have tried any harder to give the series the right wrap-up.

So yeah, there is a part of me that thinks, We have such strong characters, maybe there is another shift to do further down the line. But I sleep very well thinking that we’ve ended it now.

This interview has been edited and condensed.