Three seasons after Kendall drives a car into a river and kills a waiter at his sister’s wedding, the hanging sword of Damocles finally falls. Shiv, desperate for a reason to explain why she’s tanking Kendall’s ascension beyond her own selfishness, blurts out the secret. Kendall can’t be the CEO of Waystar Royco because he killed someone. Then two astonishing things follow. First, Kendall says “Which?” and sends his siblings into a tailspin of speculation about what else he might have done. And then, incredibly, Kendall simply says no. It did not happen. It was a story he made up. He was briefly experiencing a break from reality. It was imagined. It was never real.

The fun, distracting bauble on Succession’s surface has always been the question of who will win. But the deeper uncertainty is about whether the Roys will experience consequences. A dozen or more life-altering events have piled up at their feet over the past four seasons, including the promise of a tell-all biography, a massive magazine exposé, the risk of imprisonment, an FBI raid, testimony before Congress, and a truly uncountable number of almost-deals that either fizzle at the last second or die on the vine. Not a single repercussion has ever stuck to them. Even their election maneuvering, the finale suggests, may end up getting washed away. But this — Kendall’s complicity in causing a man’s death. This one thing has finally come back! Consequences do exist.

Except that it doesn’t come back, not really. It feels like it does. When Shiv says the words aloud, it’s like a chasm opens up in this little conference room. Kendall can hardly believe it. Roman is just as stunned and just as relieved to have a buoy for his own misgivings about Kendall’s leadership. But the cater-waiter’s death doesn’t actually play into what happens. It’s the excuse Shiv uses, but it has nothing to do with her decision or with why Kendall ultimately loses or the show ends the way it does. There’s never even clarity among them about whether this horrible thing did, in fact, happen. It’s just the reminder of a possibility.

The question of Succession and consequences can feel like a moral one. How much does it matter that these people are awful? Does the show need to punish them in the end? “With Open Eyes” does offer some solace on that front. The Roys lose. Even though they’re given enormous golden parachutes and will walk away with more freedom and privilege than 99 percent of the planet, they’ve lost the one thing they understood how to care about. Punishment complete. The much harder question remains: What kind of show is this?

Succession has always been an optical illusion begging to be read many different ways at once. The series thrived in this ambiguity; every line of dialogue can be construed in multiple ways. Every character wonders what the others mean. All the best scenes are circuses of miscommunication, suspicion, and doubt. And we have gotten to participate in that same mesmerizing game of interpretation. From one angle, Succession is a tragedy: a story about awful, broken, cruel, flawed people who could never figure out how to escape those flaws long enough to find real happiness and who didn’t care at all that their own wounds were infecting everyone around them. This is the drama plot, and despite the show’s soaring settings and high-stakes events, it often played out on the level of small character interactions. Testifying before Congress doesn’t really matter in the long run, but a few words between Logan and Kendall are the stuff of nightmares, and Shiv and Tom’s marriage has enough venom for an opera’s worth of sadness. This is a show that inherited the most potent path of the past quarter-century of hour-long prestige TV. It rewards careful, meticulous viewing, it asks its audience to track every detail; it’s about a slow-burn calamity that promises to end in conflagration. In this version of Succession, Kendall’s killing a man in season one matters. It’s plot. It’s conflict. It’s a rubber band held taut, waiting to get snapped onto some unsuspecting expanse of exposed flesh at the most vulnerable possible moment.

The other angle of Succession is that it’s a comedy, and not just because Tom occasionally says things like “king of edible leaves, his majesty the spinach.” More often than not, Succession is structurally a sitcom with episodes bounded by themes and character arcs rather than closed procedural plotting. It’s why, despite its perpetual busyness, Succession has also been a show about nothing actually happening. The Roy siblings spend three seasons caught in stasis: the fictional one created by their father’s weaponized ambivalence, and the stasis of Succession’s class commentary, which shelters them from repercussions as a way to demonstrate their untouchable bubble of wealth. Succession fell into a circling, repeating pattern of playing with its own genre, threatening to pile up into something like a plot while remaining a dark comedy of wealthy goons, forever fired up by incompetent ambition, reaching for the gold ring, failing, and then continuing around the carousel to try again. (In the worst of all possible worlds, Succession could’ve been Seinfeld, moseying along as a beautiful, consequence-free sitcom about bad people living their lives, only for the finale to wallop everyone with the abrupt, unearned return of all the people they’ve harmed.)

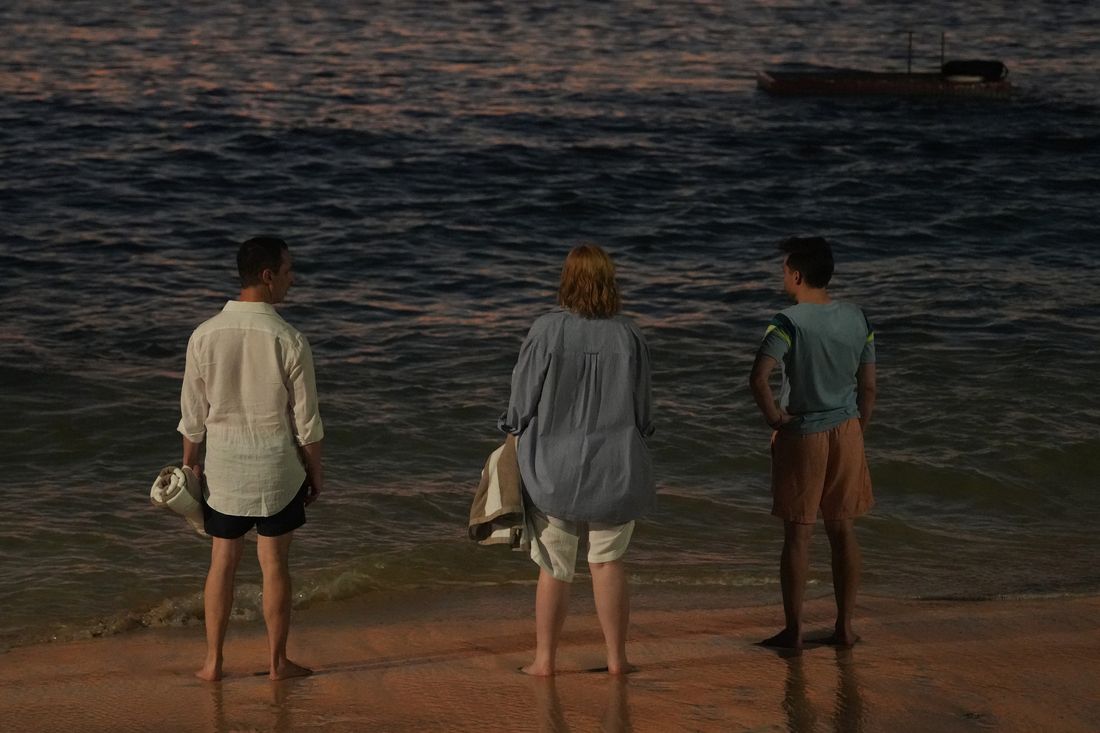

But the Succession finale, miraculously, impossibly, finds a way to land without ever choosing a side. It does not wholly abandon its sitcom instincts. The first hour is pure comedy with a heartwarming show of sibling unity and a home-video scene that feels like extra-fictional fan service — Karl singing, Connor doing a Logan impression, Gerri reciting a limerick. The last half hour is a building collapsing in on itself. Roman is so distraught he can comfort himself only by opening the stitches on his forehead. Shiv finds herself turning into her mother, sitting next to a husband who does not need her to solidify his power and hoping he’ll keep her around, transforming into everything she most despises. Kendall stares out at the water, reaching for oblivion in one way or another.

The incredible linchpin of it all, the encapsulation of this show’s remarkable refusal to commit, is that conversation about Kendall’s past. It’s a demonstration of potential: See? Things can come back. All of it, all the dangling threads, all the possibilities are still out there like traps that can be sprung. If what you needed from Succession was a show where the Roy family’s crimes mattered, there’s this scene, ready and able to offer that version. It’s Succession as sweeping drama, a media epic for the decline of an era. In the same breath, it’s all negated. Kendall insists it never happened. Shiv and Roman are upset about it, but it was also just a thing to point to, an easy justification to do what they wanted. It’s a comedy of manners, and they all walk away rich.

Succession loved to play in all the ambiguous spaces. Its language is full of conditionals, its genre tilts and warps depending on how you view it, and its most frequent device is the unfinished business deal, a probable space built out of contractual language and angry phone calls. It was a show about people desperately trying to read one another and often failing. Its brilliance lay in its ability to support many readings at once, to allow many coexisting interpretations. No wonder we love to argue about it. No wonder we’ll miss it. It’s why Succession has been so absolutely delicious to watch, even when it was also fucking bullshit.

More From ‘Succession’

- Is Kathleen Kennedy’s Star Wars Empire Ending?

- Maybe Ben Affleck Should Just Read Fan Fiction

- Enjoy J. Smith-Cameron’s Martini-Themed Crossword Puzzle ‘With a Twist’