This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

All of his colleagues at the Civic Development Group agreed that Patrick J. Pespas was a telemarketing legend. Before he got into recovery, he would do heroin in the office bathroom, nod off for a second, then jump right into a call — and land the sale. He’d once been busted for growing a few marijuana plants — okay, it was 48 pounds’ worth — in a ditch off the side of the highway. There had been consequences: He told a story about OD’ing at the office only to be roused by a boss, who put him back to work. Pespas got into telemarketing in the mid-’90s after seeing a storefront whose windows were completely covered with signs proclaiming JOBS JOBS JOBS. When he walked in, the manager asked how smart he was. He said average. “He goes, ‘I like stupid people,’” Pespas recalled. “‘The reason I like stupid people is if you do everything I instruct you to do, you will do great at this job.’”

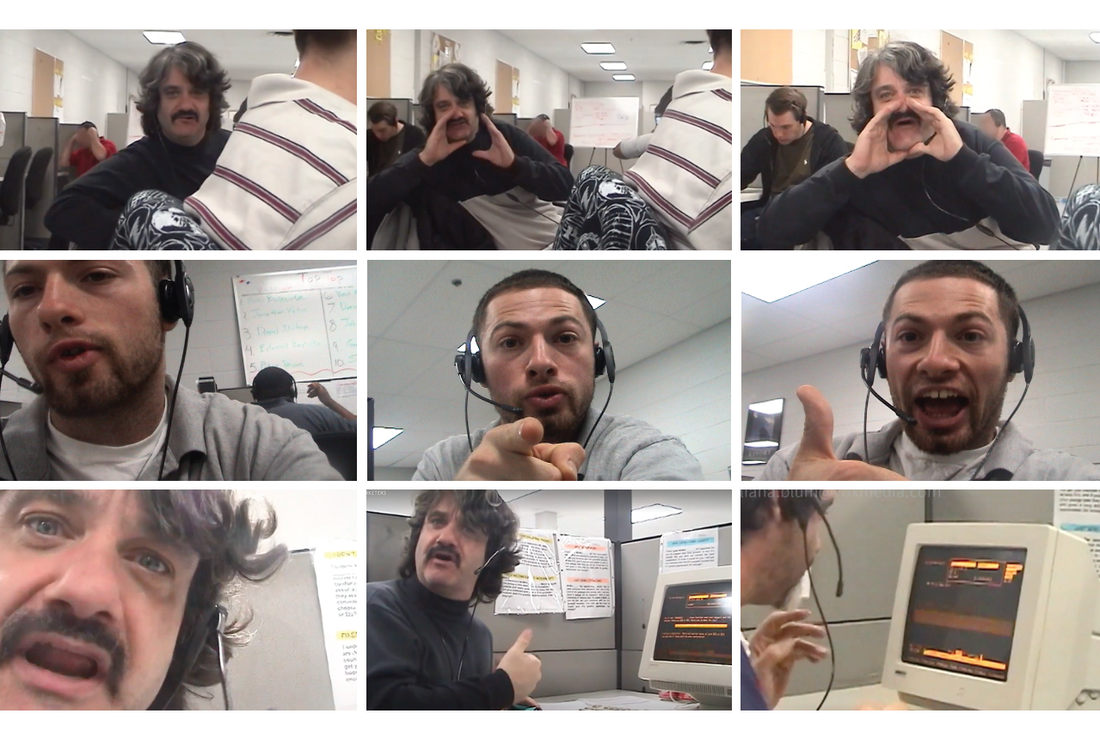

Pespas isn’t stupid, but he still did great. What was his secret? “High energy, loud voice, personable — that’s it.” He let his teenage work buddy Sam Lipman-Stern film him making calls and snorting heroin because, well, the kid filmed everything that went down at their office. This was New Jersey in the mid-aughts, and they spent their days at CDG asking for donations on behalf of police unions, children’s-cancer charities, and “every paralyzed-veterans chapter you could think of,” Pespas said. You had to be a little fucked to make call after call for ten bucks an hour, wringing old ladies for money while absorbing heaps of verbal abuse, so management let employees do whatever they needed to get through it. Besides the open drug use, there were wrestling matches, tattoo sessions, sex work, puppy sales. CDG would hire anyone from ex-cons to literal children like Lipman-Stern, who started working there as a 14-year-old high-school dropout. The only job requirement, Pespas used to joke, was being “able to pronounce ‘benevolent.’”

Some of the organizations they fundraised for were real, others bogus. What they had in common was that CDG was taking up to 90 percent of the donations it solicited. It added up. Before the company was shut down by the Federal Trade Commission in 2010, Pespas estimated the New Brunswick office was pulling in around $100,000 a day. But CDG’s downfall didn’t stop the grift — soon, Lipman-Stern and Pespas realized it went far beyond one company. Now the footage they made together forms the spine of the three-part HBO docuseries Telemarketers, directed by Lipman-Stern and his cousin-in-law Adam Bhala Lough, which covers the rise, fall, and surprising afterlife of the firm. Says one former caller, “Every other telemarketer who drives you crazy in the whole world is because of CDG.”

Produced by the Safdie brothers and out August 13, Telemarketers is part Jackass-style debauchery, part Michael Moore–style exposé, and a fantastically fluorescent piece of Bush-era kitsch. Early episodes toggle between behind-the-scenes footage of CDG callers working their dark magic and talking-head interviews with former employees, who have no illusions about the firm but are still shocked by the grubby details. Later parts of the doc, shot over the past couple years, shift the focus to Lipman-Stern and Pespas’s efforts to expose similar schemes happening now, as the project becomes a documentary about making a documentary.

Sitting in a Mexican restaurant near the train tracks in New Brunswick, a short drive from the old CDG office, Lipman-Stern, now 36, and Pespas, 54, said they didn’t immediately catch on to the scale of the fraud. They knew how little actually went to the organizations but “just thought this was how the cops raised their money,” Lipman-Stern said. Then they came upon old news stories from the ’90s, including one about how CDG had been sued for pocketing donations meant to go toward bulletproof vests. “Pat was like, ‘Yo, I worked on that campaign,’” Lipman-Stern recalled. As they tried to figure out what was really going on, the duo’s videos slowly evolved from workplace shenanigans to interviews with their colleagues and managers. Pespas left his friend a voice-mail on his flip phone: “We can’t fuck around anymore. We gotta take ’em down from the inside.”

Lipman-Stern had been fired from CDG before it shut down for posting his videos of office high jinks on YouTube. (Managers later invited him back.) But in Pespas, he didn’t just retain access to the company — he had a star. With his jaunty mustache, bright-blue eyes, and fierce Jersey accent, Pespas turns out to be one of those people who lights up onscreen; he charms the camera the same way he charmed potential donors. “They’re keeping tabs on you, America!” he’d say, looking straight at his imagined audience. “Pat never puts on airs,” Lipman-Stern said. “He’s a real person with a really pure heart.”

After CDG shut down, the pair continued their research and made a discovery. Court documents showed the firm’s most crooked move — a “consultant model” by which callers claimed 100 percent of donations would go to groups like a local Fraternal Order of Police — had sometimes come at the behest of the organizations themselves. Rather than being the victims of the scam, these groups appeared to be active participants. “We’d see the story on the ten o’clock news, but they’d only touch the surface: ‘Fuck these telemarketers.’ The rabbit hole goes much deeper than that,” Lipman-Stern said.

They hired a film crew off Craigslist and started interviewing charity experts and people who had been scammed. Being Michael Moore was harder than it looked. They were two unemployed telemarketers with zero connections. Plus, as Sam says in the doc, he’d never considered that they might be bad at this part. The interviews were faltering and awkward, as if they weren’t sure what they were trying to accomplish. Some of the footage became Lipman-Stern’s undergrad-thesis project at Temple University, but the investigation fizzled out.

Pespas got into recovery, went back to school, and cared for his wife as she battled cancer. (Watching the footage of himself at CDG “makes me cringe,” he said. “I don’t act like that anymore. I’m an adult.”) Lipman-Stern moved to L.A. and had a stint making foot-fetish videos, “literally filming girls’ feet for YouTube,” which he clarifies is “not my thing.” After working in production and editing for a few years, he had a lucky break in 2019 when he met Bhala Lough, a documentarian who is married to one of his second cousins. The older filmmaker had a development deal with Danny McBride and David Gordon Green’s production company, and Lipman-Stern pitched him on turning his trove of CDG material, which he’d meticulously backed up, into a legitimate documentary.

Bhala Lough took it to an Airbnb near the Mexican border. “I was in the desert for a week. Smoking copious amounts of weed, watching this footage all day and all night,” he said. “It was a hard drive of hundreds of hours of random stuff, none of it labeled. It was a fucking mess, but the footage was gold.”

According to Bhala Lough, he was “the Dr. Dre and Sam was the Eminem” of Telemarketers: It was Lipman-Stern’s story, but Bhala Lough knew how to shape it and had the connections to get the Safdies and HBO involved. Lipman-Stern and Pespas picked up where they left off nearly a decade before, this time armed with an actual budget and people who knew what they were doing. They interviewed a former co-worker now based in Florida who’d started his own telemarketing firm and spoke about his dealings with police groups. They even met with Connecticut senator Richard Blumenthal, who busted telemarketing scams in the ’90s and appears uneasy around these two regular Jersey guys.

“A lot of people think that the calls are annoying so they’re the victim,” Pespas said. “You know who else is the victim? The police officers, the firemen, the veterans, the cancer patients. They got ripped off too.” In the course of their investigation, they met a Chicago cop named Mike Byrne who was wounded in the line of duty. Byrne’s police union raised huge sums off stories like his, but he didn’t see a dime. “At CDG, they didn’t tell you that,” Pespas said. “You research this stuff, you grow as a human being, and you — ”

“You try to make things right,” Lipman-Stern said.

The series doesn’t end with catharsis. Its biggest revelation may be the former CDG employees: working-class people who couldn’t afford moral scruples about the gig but didn’t lie to themselves about what it was, either. “We never wanted to demonize the callers,” said Lipman-Stern. “A lot of people felt like they were at the bottom of society. But because of that, everyone gave each other respect.”

After putting his findings out there, Lipman-Stern is content that he’s done all he can. But Pespas has a larger goal. Since meeting Byrne, he has dreamed that the fundraising industry might be reformed; he wants to testify before Congress with a proposal for a unionized, transparent telemarketing industry that provides good local jobs and sends money to the people who actually deserve it — “And if it don’t work, then get rid of them.”

The thing about telemarketing is that even some of the people who work in it admit that it shouldn’t exist. “One of our buddies is a manager right now,” Lipman-Stern said. “And he texted me about the series, like, ‘I can’t believe you fucking pulled it off. You guys are geniuses.’”