On September 30, an invitation to the most famously toxic gay birthday party in the history of New York City will go out once again when Netflix releases its film version of The Boys in the Band. It has been 52 years since Mart Crowley’s open wound of a drama, in which nine gay men get together for a long evening of cocktails, cake, and tearing into one another and themselves, premiered Off Broadway. It was acclaimed, then dismissed as a self-loathing relic of an unenlightened time, then acclaimed again as a milestone of frankness, empathy, and even liberation. This, its latest and most accessible return, should feel like the summit of its rehabilitation as an essential text of gay history, enshrined by a gay producer, Ryan Murphy; a gay director, Joe Mantello; and an entirely out cast led by Jim Parsons and Zachary Quinto, none of whom are doing anything in the least bit risky to their careers. And yet, even half a century later, The Boys in the Band defies the easy triumphalism of “Look how far we’ve come”; it’s too tough and brutal to be the occasion for a victory lap. Just like the characters themselves, you enter expecting a celebration, only to encounter something much more troubling.

That lack of compromise speaks very well for the durability of Crowley’s work, which tells the story of Michael (the characters are first names only, in the all too appropriate style of an AA meeting), a semi-lapsed Catholic who is trying to cut down on his drinking and has a mean streak as wide as a river of acid (especially when he drinks), and his attempt to throw a party for his frenemy, Harold, a self-described “ugly, pockmarked Jew fairy” who masks his insecurities with a demeanor of icy hauteur and unshakable self-possession. The guests — mutual pals, former lovers and their current partners, a 20-dollar hustler, an unexpected college roommate from long ago — converge on Michael’s shabby duplex for an evening of fun and games that, by its end, turns into games but no fun, reaching its nadir when Michael baits them all into picking up the phone, calling the person they love most in the world, and telling them, “I love you.” His cruel goal is to show them all that their gay lives can never be anything more than a travesty of human connection enacted for giggles or points on a scoreboard. But the game playing, just as it does in Edward Albee’s clearly influential Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, reveals something else — a depth of emotion that gives the play its lasting power.

The critical reaction to Boys when it first opened, even from those who liked it, is horrifying to revisit. In the New York Times, Clive Barnes called it “screamingly funny as well as screamingly fag” and, while warning that “camp or homosexual humor … like Jewish humor … is an acquired taste,” saluted Crowley for how well he captured “the special self-dramatization and the frightening self-pity — true I suppose of all minorities but I think especially true of homosexuals.” As infuriating as it is to know how recently and casually gay people were discussed with anthropological detachment, it is equally painful to realize how much of the praise Boys received was for what was seen as its daring in depicting how awful gay lives really were.

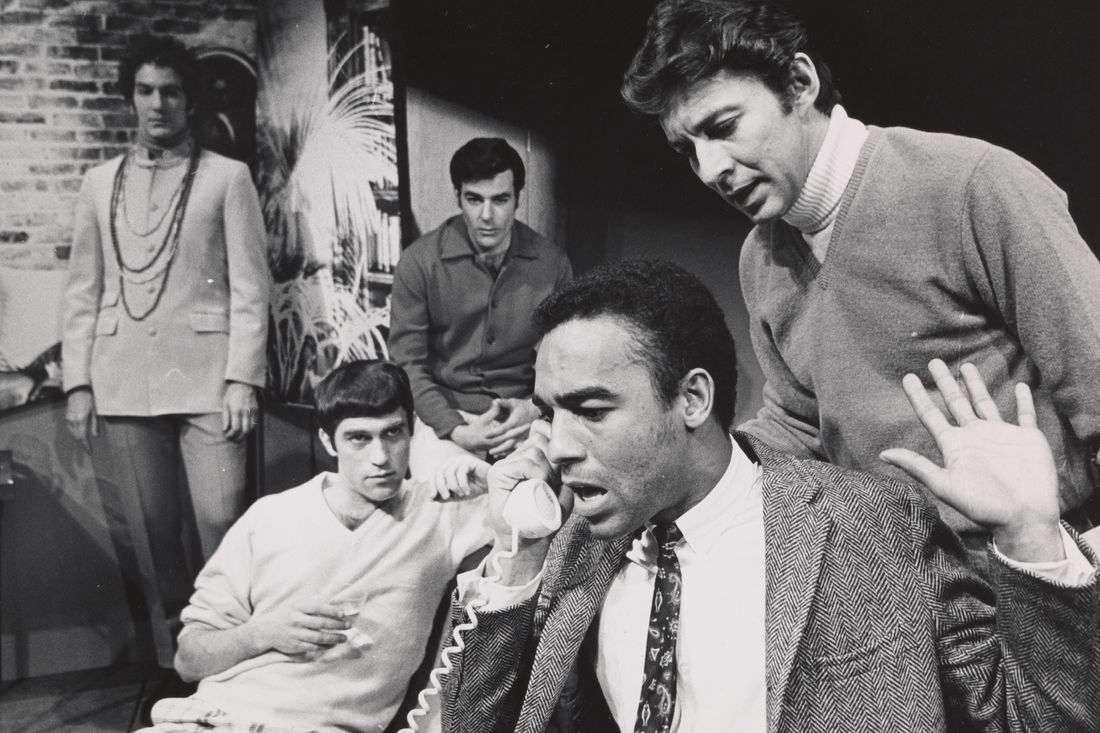

The show was a hit. Curious audiences kept the play running for more than two years, and in 1970, William Friedkin directed the original cast in a movie version. But by the early 1990s, The Boys in the Band was regarded as an antique that had written its own obit with the caustic line “Show me a happy homosexual and I’ll show you a gay corpse.” It was then that I first heard about the play (actually, the movie, which would turn up at revival houses now and then), and I remember thinking, Thanks, I’ll pass. In the middle of an existential threat to gay lives, a play whose purpose seemed to be to confirm all the worst things straight people ever said about us was the last thing I wanted to see. When I reluctantly went to the movie anyway, I understood what I hadn’t before: The Boys in the Band was, to use the slang of the time, FUBU — art made for us, by us — a time capsule, sure, but also a rich, complicated truth session from an artist who didn’t really care what impression it made on straight people; it didn’t belong to them.

By the time I saw the film, AIDS had killed the play’s original director and five of its nine cast members. Crowley survived that pandemic and lived long enough to see Boys embraced by new generations with an Off Broadway revival in 1996 and another in 2010. I interviewed him for an onstage talkback after a performance of the second revival; he seemed shy, abashed, and a little disoriented by the torrents of applause, blinking as if, having lived in the shadows for so long, he couldn’t quite believe he was being allowed back into the light.

Crowley finally won a Tony two years ago when the play debuted on Broadway with the same cast and director as this new film; he died in March at 84. The Netflix movie is likely to be his final creative legacy, and it arrives at a good moment. It’s time for us to have another awkward, painful dance with a play that challenges current audiences in some ways they may not be used to.

At a moment supersaturated with anodyne statements about the importance of representation and of telling our own stories, here’s a piece of work that refuses to fill that prescription comfortably. Viewers unsettled by characters who are not readily identifiable as either heroes or villains, or by writing that resolutely refuses judgment, are unlikely to take well to the play’s lack of reassurances. The Boys in the Band has ideas about cruelty begetting cruelty, but Crowley is bracingly uninterested in making anyone feel better. His characters, all in their late 20s or early 30s (the film has shrewdly extended their age range into the late 40s), are not role models or “steps forward,” but the new film also makes clear that they can’t be condescended to as period-piece embodiments of oppression. If, for instance, it’s jolting to see the casual racism of a predominantly white gathering of gay men noted and challenged, it’s doubly so to realize that Crowley was prodding at this hot topic decades before Twitter was. The ugliness that pours out of Michael — and Parsons, in go-for-broke mode, spares audiences nothing — is, even today, a shock. But it’s just as jarring to see most of the other characters barely raise an eyebrow at it.

Any director who tries to adapt a play into a movie has to decide how much to concede to the camera’s default demand for realism. It’s a particularly challenging question for The Boys in the Band, which Crowley wrote in a heightened, deliberately brittle, strenuously arch style that gives any audience member who wants to ghost permission to do so by calling it “stagy” or “theatrical”; it remains an easy play from which to recoil if you’re looking for a reason.

Mantello doesn’t give you that out. For one thing, he has solved the problem of the set. The original production didn’t have one — it was just a group of chrome and Naugahyde chairs and side tables that Crowley, in the stage directions to the sequel he wrote, hilariously calls “dramatic and anal … it should positively scream ‘taste.’ ” (Yes, there’s a sequel; to quote one of the characters, “Oh, Mary, don’t ask.”) Since then, the set — Michael’s apartment — has been rendered as everything from kind of grubby (the first movie), to immersive (the 2010 revival, in which the audience essentially sat in the living room), to improbably luxe (the Broadway revival). In this movie, it feels like what it was always meant to be: a modest, unflashy set, a place for someone who likes to stage drama in his home and knows how to make room for the action to play out. There is a balcony, accessible by a spiral staircase. There’s even a sort of proscenium — the terrace, visible through a set of French doors, where the friends are camping it up when Michael’s college buddy walks in. In this version of the play, more than any other, the manipulative, insistent Michael comes off as a kind of failed director.

That’s one of many smart decisions Mantello makes; another is to keep The Boys in the Band real while leaning into the kind of artifice the play demands. He knows there can be no such thing as a relaxed or naturalistic version of Boys because, for most of its characters, the night itself is a tense performance. In the movie’s first minutes, he gives us fleeting glimpses of their lives outside that apartment — the decorator, the squash player, the porno-house cruiser — and we start to understand that, for many of them, walking through that door and presenting themselves to other gay men on a Saturday night requires a willed act of, in essence, getting into character. The Boys in the Band doesn’t settle for the sentimental idea that we automatically drop our guard around people like ourselves. For most of those celebrants, that apartment will prove no more of a safe space than any other, and Mantello is acutely aware of how quickly even the one moment of cutting loose that the men permit themselves — a joyful sing-and-dance-along to Martha & the Vandellas’ “Heatwave” — can turn into an occasion for anxiety and shame.

Mike Nichols once said there were no great movies of Chekhov plays because the plays themselves are master shots; both their comedy and their tragedy accrue from the cumulative effect of seeing all the characters onstage together virtually all the time. If Crowley’s play isn’t exactly Chekhovian, its sense of ennui and despair and confinement comes close enough, and when you see it onstage, your eyes often drift to characters who aren’t talking but watching as the slow-motion nightmare unspools. A movie can’t replicate that effect; almost by definition, a camera makes choices, and so a movie becomes about people taking action, doing things. That could be a hazard for The Boys in the Band, which is, in so many ways, a play about being stuck, not moving forward. But, somehow, it works. If the 1970 film, directed by a straight man, turned the audience into tourists, Mantello’s eye makes us silent guests at the party, peering through a looking glass at who, by an accident of birth timing, we might have been and how far we have or haven’t traveled from that.

By the end, I was aware of what a necessary reminder The Boys in the Band is that the struggle continues. Halfway through its original Off Broadway run came Stonewall, a date that has been commodified and oversimplified as a line of demarcation. But Boys isn’t cleanly readable as either a pre- or post-Stonewall work; it’s one in which constraint and freedom, pride and self-loathing, masochism and an unkillable survival instinct all exist in the same room on the same night. Many of the younger gay men who may decide to watch Boys in the coming weeks have grown up on a Bravo-VH1 diet of overstaged confrontations. They know all about reading someone (“The library is open!”), about “living for the drama,” about savage takedowns — not to mention about the sexual hierarchies of Grindr. It’s upsetting, in the best possible way, to look at where some of that originated and at how much of it is toxic. After all, what is RuPaul’s mantra “If you can’t love yourself, how the hell you gonna love somebody else?” but a think-positive rewrite of the still-heartbreaking line at the play’s end, when Michael, the self-styled illusion shatterer who has managed to shatter nobody but himself, pleads, “If we could just learn not to hate ourselves quite so very much.” Crowley left that sentence unfinished. Writing its ending is, as this vital revisitation of his work reminds us, our job.

*This article appears in the September 28, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!