By now, any hip-hop fan worth their kicks ought to know where this music comes from. But for the uninitiated (or those too young to remember when local crew Boogie Down Productions heralded it in song), the South Bronx invented a genre that became a movement that became the biggest sound in the known world. Even the Google Doodle people recognize DJ Kool Herc’s August 11, 1973 “Back to School Jam” at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue as the birthplace of hip-hop. But the real story begins years before that landmark event. In the Bronx (as well as upper Manhattan and other outer boroughs), white flight to the suburbs, a dearth of economic opportunity, and the effective ghettoization of Black and Latinx New Yorkers from the 1960s into the 1970s left the city’s neediest communities in dire straits. Street gangs largely organized around ethnic and racial lines engaged in territorial battles. Fights between rival groups were typically bloody, and the violence limited the ability of young Black and brown people to between — or leave — these neighborhoods.

Following a particularly violent series of incidents that led to the 1971 murder of Cornell “Black Benjie” Benjamin, a prominent Puerto Rican leader in the socialist-minded gang Ghetto Brothers, a peace meeting was held at the Boys Club on Hoe Avenue in the Bronx. And while it certainly didn’t put an end to violence in the city, the multi-gang treaty that emerged from this unprecedented gathering allowed for something like the Back to School Jam to be possible. That party, and other similar uptown functions, brought together both Black and Latinx gang members along with their friends, siblings, and cousins. An attendee of the event, local DJ Luis Cedeño aligned with his friend Grandmaster Caz and formed the Mighty Force crew. Half Cuban and half Puerto Rican, he became Disco Wiz, the first Latin DJ in hip-hop.

Despite the undeniable history of Latinx contributions to hip-hop, the visibility of Latinx people in the 1980s NYC hip-hop scene was surprisingly limited. Prince Whipper Whip and Ruby Dee — both vocal members of Grandwizard Theodore’s seminal Fantastic Five — represented with pride at the start of the decade on 1980’s seminal single “Can I Get A Soul Clap.” DJ Charlie Chase of the Cold Crush Brothers would regularly infuse the sounds of Latin music into his routines and later on his vital WBLS radio broadcasts — though his most visible contributions to Charlie Ahearn’s 1983 rap film Wild Style and its soundtrack were about scratches, not salsa.

Many of the original crews splintered (as was the case of the Treacherous Three’s Kool Moe Dee), fizzled out, or were supplanted by comparatively newer acts like Run-D.M.C. (Disco Wiz, tragically, was charged with attempted murder in 1978. He spent four and a half years behind bars and lost much-needed momentum at a critical point in hip-hop history.) With known roots in the gang known as the Black Spades, Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force pushed a more Afrocentric vision of the genre via the standout singles “Looking For The Perfect Beat” and “Planet Rock” (though his Universal Zulu Nation organization did include Latinx members, most notably on the breakdancing side). Their takeover meant that the public face of hip-hop often looked exclusively Black, especially to white outsiders.

Nonetheless, in these early stages, as the genre began to grow beyond the confines of block parties and public park jams, Latinx people naturally remained an essential part of the listenership and support network even if they weren’t represented by the prevailing artists of the period. As a member of the Fat Boys, Puerto Rican emcee Prince Markie Dee served as one of the few exceptions— though the Brooklyn group’s massive crossover singles with the Beach Boys and Chubby Checker didn’t exactly play up his background. Still, the sound of hip-hop boomed through the streets of New York City, especially in neighborhoods where Black and Latinx residents lived.

As the 1980s transitioned into the 1990s, rappers Kid Frost and Mellow Man Ace began to establish themselves in Los Angeles with their respective albums Hispanic Causing Panic and Escape From Havana. Regrettably, the coastal rivalries between East and West — beef that was sometimes complicated by gang affiliations — tended to silo these artists and their peers’ potential for national recognition. Though likely unintentional, Gerardo’s 1990 Billboard Hot 100 charting hit “Rico Suave” slighted these sincere and street-wise contributions to the hip-hop conversation with Spanglish–reinforced stereotypes. Compared to his prior food-based singles, comedian Weird Al Yankovic’s 1992 parody version “Taco Grande” felt less like a tribute than it did an outright insult. Even as Cypress Hill proved with their multi-platinum 1991 eponymous LP and its even-more-successful 1993 follow-up Black Sunday that mainstream acceptance for non-novelty Latinx hip-hop artistry was in fact possible, New York lacked a comparable parallel.

Now a solo artist moving past the novelty of the Fat Boys’ Disorderlies–era peak, Prince Markie Dee dropped the aptly titled Free as his 1992 debut. Though not shying away from his heritage, his savvy rebrand as the overweight lover type with a thuggish streak defined both that album and its 1995 successor, Love Daddy. Around the same time as Free, Afro–Latinx rapper Chino XL was only just starting to make some noise as half of Art of Origin with Rick Rubin’s post–Def Jam sub-imprint, Ill Labels, within American Recordings. Meanwhile, a Queens–based duo called the Beatnuts had begun making moves behind the boards. Comprised of JuJu, who is Dominican, and Psycho Les, who is Colombian, the pair would eventually drop a project of their own. But their production touched two incredibly important recordings of the time which, while not tremendous sales successes, set the stage for the decade’s eventual platinum-certified Latin rap superstar, Big Pun.

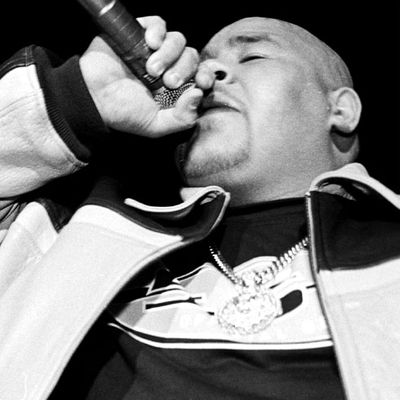

The Beatnuts’ rugged rhythm behind “This Shit Is Real” sits on the back half of Fat Joe Da Gangsta’s 1993 debut Represent for the Sony Music–acquired Relativity imprint. With lyrics that affirm both his South Bronx bonafides and his Puerto Rican heritage, the track showcases the then-23-year-old Diggin’ in The Crates rapper’s raw and profane style (as does the rest of the largely Diamond D–helmed album). His rhymes across Represent exist as a darker and more youthful yang to Prince Markie Dee’s contemporaneous pop-wise yin, though the future Terror Squad majordomo certainly wasn’t opposed to hollering at the ladies on “Shorty Gotta Fat Ass.”

Though Represent didn’t make big waves on the Billboard 200, the single “Flow Joe” charted on the Hot 100, peaking at No. 82. If nothing else, it reflected a public appetite for the kind of hardcore hip-hop Joe was slinging. Indeed, New York was flush with like-minded, street-oriented music. 1993 gave us albums like Onyx’s Bacdafucup, Black Moon’s Enta da Stage, and the Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers). But Represent refocused things on the reality of the city’s Black and Latinx cohabitation and the ways in which the various cultures within these communities — and their criminally minded subsets — were inextricably linked. That would prove a hallmark of Joe’s subsequent, and more commercially successful, recordings.

To a lesser extreme, Puerto Rican and Cuban rapper Kurious had also seen some success when he threw his Harlem–worn cap into the ring the year prior, in 1992, with another Beatnuts production. Released as part of a partnership between Columbia Records and Hoppoh, the imprint of DJ Bobbito and 3rd Bass member Pete Nice (an auspicious pair), his “Walk Like a Duck” single talks smack from the block the way only someone from the block can. With a jazz-flecked beat closer to Prince Paul than RZA, he made a good first impression ahead of the following year’s A Constipated Monkey. Dropping mere months ahead of his labelmate Nas’s Illmatic, Kurious’s full-length debut owes more to the Beatnuts than Fat Joe’s Represent did. There’s a lyrical whimsy in his rhyming style, well-suited for a jokester who can also out-rap anyone in his immediate vicinity. Accessible without compromising his authenticity, “I’m Kurious” and “Uptown Shit” swung with the best of what appeared on the radio at the time, though A Constipated Monkey couldn’t quite get to that RIAA gold threshold.

Nonetheless, when Big Pun emerged just a couple of years later on Fat Joe’s Jealous One’s Envy standout “Watch Out,” it was hard not to tell where he came from in the hip-hop tradition. Inheriting the labor of his immediate predecessors, his proprietary blend of innately gifted humor and hood-hardened heft echoed Kurious’s and Fat Joe’s respective skill sets — as well as their commitment to wearing their ethnic pride on their sleeves. In subsequent decades, the Latinx presence in hip-hop continued to bloom. Reggaeton would become a movement of its own in the 2000s, and Latin trap made such an indelible dent in streaming in the 2010s that even English–speaking superstars would enlist their talents to get a piece. But make no mistake: The Latinx community was a part of New York City hip-hop from the start.