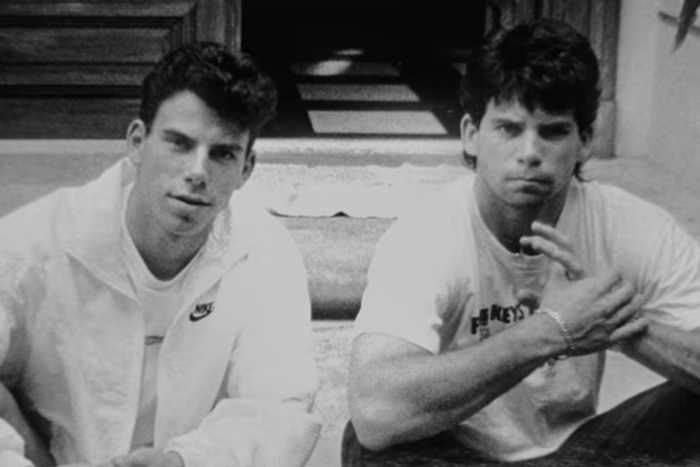

Less than three weeks after the debut of Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story, Netflix has delivered The Menendez Brothers, a two-hour documentary that’s both more biased and more clear-eyed about the case than the limited series.

The Ryan Murphy/Ian Brennan drama offers multiple explanations for the brothers’ motives, but the central one aligns with what prosecutors argued: that the siblings ruthlessly blew away their parents, Jose and Kitty Menendez, with a pair of 12-gauge shotguns so they could inherit the family fortune. The documentary, directed by Alejandro Hartmann, more blatantly sides with the brothers’ version of events, asserting that years of sexual abuse by their father, who had threatened to kill them if they ever told anyone, prompted the pair to commit such a heinous crime.

While the limited series extensively explores how the boys were molested and psychologically destroyed by their father, the documentary goes a step further by suggesting the pair should have been convicted of manslaughter rather than first-degree murder because they were victims who mentally snapped, not cold killers who premeditated the crime. That perspective, based in part on 20 hours’ worth of recent prison phone calls with the Menendez brothers, will no doubt be embraced by supporters of the siblings, who, along with Erik Menendez himself, criticized Monsters for its inaccuracy and casting doubt on the brothers’ abuse claims. Prosecutors and many members of the public during the brothers’ trials believed the two had made up the abuse story, and one of those prosecutors, Pamela Bozanich, appears in the documentary asserting, “That whole defense was fabricated. It was done artfully, but it was fabricated.”

Because Hartmann is so committed to empathizing with the brothers, the narrative he unspools is more straightforward than Monsters and provides helpful additional context. But it also ignores crucial details about the case that are raised in Monsters, making it too one sided to qualify as the definitive consideration of the brothers’ story. If the point of The Menendez Brothers is to set the record straight about their case, it should address all of that record. Here’s how the two projects compare on key points.

What The Menendez Brothers Tells Us That Monsters Does Not

Jose Menendez was verifiably worse than Monsters suggests.

In the limited series, Jose is depicted as emotionally and physically abusive toward his sons — he routinely berates and belittles them, in public and in private. The series also contends that he sexually abused them via emotional confessions where Erik and Lyle, privately and on the witness stand, describe the way he molested and raped them while their mother turned a blind eye. But because Monsters also offers equally compelling evidence that the brothers made up the abuse story, one can walk away from the final episode thinking that Jose was bad but maybe not that bad.

The Menendez Brothers completely disabuses the viewer of that notion. Both Erik and Lyle remain steadfast that their dad began to molest them starting around the age of 6, and both talk about the shame they had to work through in order to feel comfortable talking about it. In footage from the 1993 trial, both brothers seem genuinely pained when describing the abuse they endured, and in one of the audio interviews, Lyle discusses his ongoing efforts to help fellow abuse survivors in prison. All of this behavior seems inconsistent with people who are concocting traumatic tales. Aside from Bozanich’s comments about their defense being “fabricated,” the documentary takes the Menendezes at their word, something Monsters does only in part.

More compelling are interviews with relatives, particularly cousin Diane Vander Molen, who says, as she did during the 1993 trial, that Lyle told her his father was molesting him, but when Vander Molen brought Kitty Melendez into that conversation, the mother brushed it off.

Even Bozanich attests to how vile the elder Menendez was. “I couldn’t find anyone to say anything nice about Jose Menendez except his secretary,” she says. “The loss of Jose Menendez, in my mind, was an actual plus for mankind.” And this is someone who still doesn’t believe the boys were actually abused by him.

The O.J. Simpson connection is more interesting and relevant than Monsters suggests.

The limited series includes several scenes that reference O.J. Simpson, including one where he’s placed in a cell next to Erik shortly after being arrested for the murders of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman. But the Simpson case is also significant in ways the drama doesn’t explore as deeply. Opening statements in the second Menendez brothers trial, which followed a previous mistrial, began one week after the not-guilty verdict was rendered in the O.J. trial. In the wake of that verdict, the documentary contends that the judicial system immediately began coming down harder on defendants, especially high-profile ones like the Menendez brothers. “This is gonna be bad for the boys, and for everyone else,” Erik’s attorney, Leslie Abramson, says in an archival interview. “It’s going to be payback time.”

This is why the judge prohibited the defense from raising Erik’s or Lyle’s abuse during the second trial, and, according to the film, a key reason why the brothers deserve to have their case reconsidered. Monsters certainly acknowledges this — in episode nine, Abramson, played by Ari Graynor, notes that L.A. County district attorney Gil Garcetti is concerned about re-election and that is why “they are trying to gut our case” — but it doesn’t connect those dots as clearly as the documentary.

The documentary provides more cultural context for the trial.

Monsters definitely touches on the notion that, by the time of the Menendezes’ second trial, the public was souring on the brothers, showing a clip from The Tonight Show to drive home that point. But a documentary, which relies more heavily on archival footage, can evoke a time period in a way a scripted series can’t quite achieve. The Menendez Brothers includes footage from various talk shows as well as Saturday Night Live, where the name became a regular punch line. (“These two arrogant brothers are going to fry,” Sandra Bernhard laughs during a chat with David Letterman.) This context helps explain why people who lived through the 1990s may sound baffled by the support the Menendezes have found on TikTok — their perceptions of the case were shaped by the public opinion back then, when society was far less sympathetic to abuse survivors, especially men.

The Menendez Brothers never suggests the boys were incestuous.

Both projects include the moment on the witness stand when Lyle apologizes to his brother for molesting him once when they were kids. But The Menendez Brothers presents no evidence that the two were ever in a consensual, incestuous relationship, whereas Monsters includes several homoerotic and outright sexual moments between the two, including scenes of provocative dancing at a party, a kiss, and a sensual shared shower. Those choices seem even more baffling and distasteful after watching this documentary, which shows the real Lyle breaking down with shame on the witness stand over his abuse of Erik.

What The Menendez Brothers Leaves Out That Monsters Includes

The documentary doesn’t mention Jose Menendez’s will.

While Monsters makes a point of the fact that Jose Menendez cut the boys out of his will, the movie does not discuss this at all. It’s one of the primary reasons the prosecution could effectively argue that Erik and Lyle were concerned about money — because their full inheritance might not be coming to them. The only reason for The Menendez Brothers to omit this information is because it doesn’t support the film’s argument.

Their post-murder spending spree is barely mentioned.

The limited series has fun playing up the excess of the luxury shopathon the brothers embarked on not long after the murders. It’s mentioned in passing in the film but neither Lyle nor Erik is asked to fully explain why they decided to spend so much cash on Rolexes and new cars. Lyle characterizes it as a coping mechanism and insists he and his brother were in deep anguish at the time, but he’s never pressed to talk about it further.

The brothers’ construction of alibis isn’t addressed.

Monsters follows the pair as they leave their parents’ home and go first to a movie, then to the Taste of L.A. festival in an attempt to convince law enforcement they discovered their parents’ bodies after they were killed. If there’s a reasonable explanation for this, the documentary does not provide them an opportunity to offer it.

The Menendez Brothers never discusses the fact that the brothers’ attorney, Leslie Abramson, used a similar defense in another case.

In Monsters, prosecutors and trial observer Dominick Dunne (Nathan Lane) say that Abramson, who mounted an abuse defense in a previous case, has simply repurposed it for this one, something she denies. While the limited series mentions this, The Menendez Brothers does not, missing another opportunity to shoot down a piece of the “they just made it up” theory. (Abramson opted not to participate in the documentary, saying in an emailed statement that appears at its conclusion: “I’d like to leave the past in the past. No amount of media, nor teenage petitions, will alter the fate of these clients. Only the courts can do that, and they have ruled.”)

What Monsters and The Menendez Brothers Both Leave Out

Allegations that Jose Menendez abused minors outside his family.

Neither the limited series nor the documentary mention, even in a title card, that Roy Roselló, a member of the boy band Menudo, said in a Peacock documentary last year that Jose Menendez drugged and raped him when he was a teenager. At the time, Menendez was the head of RCA Records, the studio that signed Menudo.

That revelation prompted Erik and Lyle Menendez to file a petition to have their convictions overturned. Last week L.A.’s District Attorney’s Office announced it would reopen the case to examine new evidence, including the allegations by Roselló. It’s a particularly notable oversight on Hartmann’s part since this information only bolsters the Menendez brothers’ case. Contrary to Abramson’s comments, this development also suggests that maybe the courts are not done ruling after all.