There is a photo I love of Jalen Rose and Chris Webber in their days playing basketball as part of the Fab Five. Rose is in Webber’s face with his head cocked, sneering out some language that appears to be so cutting, one can almost hear it through the stillness of the photo. Webber stands still, his eyes locked in on Rose, his arms hanging loosely at his side. I remember watching this scene unfold as a kid, and a white announcer suggested the interplay was adversarial, painting it as the two teammates and friends clashing. To the uninitiated, maybe. But the Black folks, even the young among us, knew better. We knew what it looked like when one of our own, someone we knew and loved, set out to hype us up. The Webber and Rose moment was a disruption of the consistent, draining hum of the wider world. The two of them built a smaller, more manageable place in which they could love each other toward invincibility.

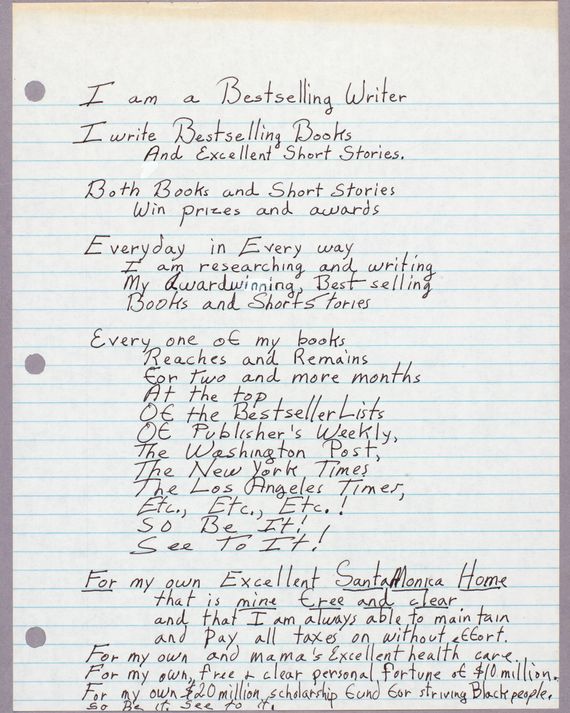

The journals of Octavia E. Butler are riveting to me for how they call back to the idea of hyping up a beloved, even if the beloved is your own reflection. I am sometimes precious about the private journals of writers or artists being made available to the public, and yet I am enthralled by hers. For their aesthetic qualities — how they are often written with what seems to be haphazard exuberance, all caps, a flurry of underlines and exclamation points, different colors of ink, edits and redirections. Removed from the cleanliness that a finished draft can demand, there’s a thrilling freedom that echoes off the page, particularly in the pages where Butler is manifesting a future for herself or laying out her desires. This tone has, in part, granted these journals gaining a new life on the internet in recent years. Portions of them are posted on social media as motivation or simply as a way to be in awe of Butler’s dreaming come to life. In one I return to, dated 1975, the year before the first book in Butler’s groundbreaking Patternist series was released, she writes, among other things:

I am a bestselling writer

I write bestselling books and excellent short stories

Both books and short stories win prizes and awards

After running down a number of best-seller lists that her books will be on, the note ends with financial goals:

For my own excellent Santa Monica home that is mine free and clear

For my own and mama’s excellent health care

For my own free and clear personal fortune of $10 million

For my own $20 million scholarship fund for striving Black People

Impostor syndrome is most commonly defined as a tangle of inadequate feelings that persist beyond achievement, overshadowing a reality of self. Much of it, by definition, is classified as an internal action, and doesn’t mention how the internal action can be informed by an external environment. Or how what we believe about ourselves is — at least in part — formed by the world’s reaction to our presence in it. Most Black artists I know have a complicated relationship with the desire for success and/or the material spoils that come with it, so often relying on a performance of humility that might be genuine to a point, but is usually designed to keep in place the envy or the finger-wagging of non-Black people who know exactly how much success they’ll allow from one of our folks. I don’t celebrate my predisposition toward humility, primarily because it largely exists out of fear that anything or any goodwill I’ve ever earned can be unearned overnight. This page of Butler’s journal, though, is riveting for how it upends any tradition of shame around a relentless desire for success. And takes it a step further, even. Butler’s use of “I am,” as opposed to “I want to be,” when she hadn’t yet published her first book, suggests an understanding that this life was already set and eager to welcome her, she was just taking her time in arriving to it.

Octavia Butler, as understood by …

The reason I find myself sometimes uncomfortable with publicizing the private journal entry is because it can be a playground for admissions of dreams and feelings that the outside world might not take as seriously as you do or be eager to turn down. Butler’s journals feel exceptionally precious as she was, by nature, a builder of worlds. In her books, she was relentless in considering the vastness of a place beyond here (or the many “here”s we are confronted with through our living) and the vast, complicated nature of Black people living and surviving in that beyond.

All of the pages in her journal, but especially this one, act as a boundary between the realities of what the world tells someone about themselves and what that person believes — or, in this case, knows themselves to be capable of, no matter how far the desires reach or how improbable they might seem to the uninitiated. There is no risk of feeling like an impostor if you believe yourself so far out of reach, so far beyond the noise that the language of doubt can’t touch you.

Even now, it reminds me that I am worthy of the work I am pursuing beyond production of a product that is received by the world. My ideas, my obsessions and curiosities deserve to be the engine for my dreaming, even if I haven’t clearly shaped them into anything that can be consumed. If it is just me and my reflection, no one can tell us a damn thing.

More on octavia butler

- ‘Our Task Was to Expand the Universe of the Book’

- The Spectacular Life of Octavia E. Butler

- Misreading Octavia Butler