This interview has been edited and condensed. It also completely spoils the ending of The Patient, so proceed accordingly.

During the six seasons they spent crafting the Cold War spy drama The Americans, Joel Fields and Joe Weisberg famously did not avoid unsettling moments or less-than-happy endings. In their most recent limited series, The Patient, they honored those same impulses, right up to the very end.

For nine episodes, the creators and sole writers of this series explored the relationship between a closeted serial killer named Sam (Domhnall Gleeson) and the therapist, Alan (Steve Carell), whom he kidnaps and chains up in his basement with the demand that Alan cure him. Viewers watched with the hope that Alan would eventually be allowed to leave and return to his normal life. But in the tenth and unequivocally final installment, which dropped today on Hulu, harsh reality sets in as we watch Sam strangle the life out of the man who tried to help him.

That distressing ending seemed inevitable, say both Fields and Weisberg, who acknowledged when talking to Vulture about “The Cantor’s Husband” that they considered other potential outcomes for the characters. “We experimented, talked about, tried on, wrote basically every version that we could imagine,” says Fields. “None of them felt like they fit until we circled around to this one.”

In gaming out the end of this series, there must have been at least one version you considered where Alan gets out and goes back to his normal life. Can you describe some of the other possibilities that you considered?

Joe Weisberg: We’d honestly be reluctant to describe them, because in a way we want this to live in people’s imagination as what it is. But I think we can fairly say that, sure, you’re right about that. I mean, there are a fairly limited number of ways this could end, and we thought about and tried out all of them. What it came down to was that this one felt true and the others didn’t, which is lucky. It’s lucky if your story lives in a way that it will tell you what to do.

On one hand, you can look at this ending and feel that Sam ended up killing Alan, so he can’t be helped. But he obviously was helped to some degree because he chooses to chain himself up. I’m wondering what you would say if somebody asked, “Is this a show about change being possible for people?” Because both of these characters do evolve, but they do it too late.

J.W.: You’re right. We don’t want to weigh in heavily — again, because you’ve just got to let the viewer go where they want to go. Although I’m sure Joel and I were equally gratified to hear your interpretation. Like, that felt good. The other thing I’ll say is that, as a general principle, Joel and I believe in change. We’ve both changed because of therapy. We look at the world and other people and believe in the potential for them to change when they want to. So we’re pro-change.

Joel Fields: In terms of that beautiful interpretation you have, one of the reasons why it’s gratifying to hear is not because it’s the right one but rather it’s so thoughtful. That, to us, is really the goal. We’re collaborators because we’re working with other artists, but we’re control-freak collaborators, so if you ask us any questions about any of the scenes that happen, we’ve got very strong points of view. But we literally don’t have any more of a legitimate point of view than anybody else on what happens afterward, or even what happened in the psychological dynamics of these characters after that ending.

There wasn’t a writers’ room on The Patient. It was just the two of you, which is different from the way The Americans worked. What was that like?

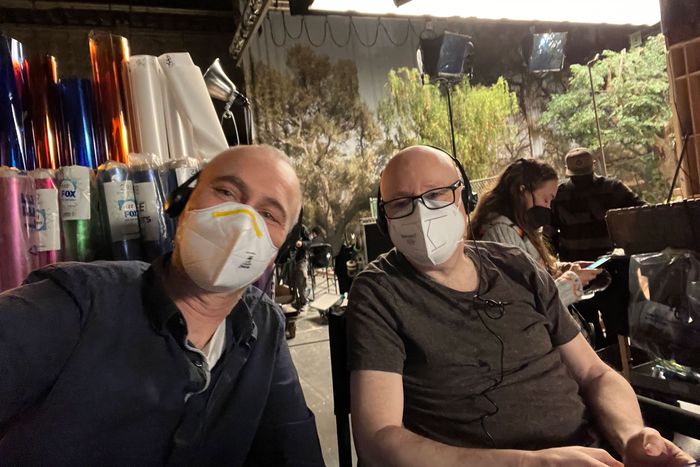

J.F.: The value of that Americans writers’ room was incredible; we loved our collaborators there, and so much grew out of that process. But when you ask how it was, I’ll speak for myself: It was fun. We were really in the throes of COVID for the first chunk of it, and so we were working on a headset or over Zoom with each other. We missed each other, and it was great to be able to just dive in, the two of us, and start exploring this fictional world and these characters. Joe is going to tell you that he was actually miserable, but I don’t care. I had a good time.

J.W.: The worst professional experience. No, the only thing I’d add to that is these were very short episodes. They were half an hour, so it wasn’t really biting off more than we can chew. We get a lot of benefits from a room, and we missed them, but these discrete little bites we were writing seemed like they were going to do better if we just put our heads together and spit them out.

Did you always envision this as a show with episodes that would be 30 minutes or so?

J.F.: Well, in its very, very, very, very, very original incarnation, it was an hour show for, I think, four to six weeks.

J.W.: That’s funny. I don’t even remember that.

J.F.: Because I remember we had other story lines and other characters that we were following. It takes a while for something to gel into what it is.

J.W.: I remember we were in some meeting with FX about something totally different — maybe it was long before we started this — and somebody at FX randomly mentioned the phrase half-hour drama and I immediately in my brain was like, That’s all I ever want to do again. I don’t even know what it is. I’m in.

Do you still feel that way?

J.W.: Totally. I mean, first of all, when it’s longer, there can be a kind of pressure of something you have to fill out. But when it’s really discrete like that, there’s zero outward pressure. You just do whatever you want. Look, the response is mixed. Some people are like, “I wish it were longer,” and some people are like, “Boy, when I saw it was 20 minutes, I was so glad.”

I also felt like it worked so well for the kind of story you were telling. If it had been much longer, it would’ve defused a lot of the tension. I thought that was very much to the show’s benefit.

J.W.: I completely agree with that, and I also think that we knew it was going to be 90 percent in one location. So the idea of limiting the time we were asking the audience to visually have something limited was a plus.

Let’s talk about Candace. My interpretation was that she feels responsible for what has happened to Sam, so she’s overcompensating by never making him take responsibility for what he is doing. I know you guys did some research going into this. Did you find any information about parents or loved ones of criminals or serial killers who reacted in a similar way?

J.F.: I don’t think that was a matter of particular research, although certainly there are a lot of parents who don’t turn their kids in. There’s not a lot of research that I’m aware of on the parents of serial killers. So we were relying in part on our own intuitions and our own storytelling there and somewhat on conversations with our technical-adviser psychologist. It was more a sense of understanding this character and what his relationship with his mother might have been in these particular circumstances.

J.W.: There’s a trope of the serial-killer mother, which is she’s just caused him to be a serial killer by how fucking crazy she is herself. We really didn’t want to go in that direction because we thought it was not interesting. But if you imagine the craziness that all people can achieve, it’s not hard to believe that a mother would not turn in her son. What we wanted to explore was that she’s also got a functional connection to the world outside. So she’s got those two things competing, and how would that play out in the real world?

What else did you get from that research?

J.F.: One of the things that was most surprising to both of us was that so many of them didn’t like it, that it didn’t make them feel good. Like many addictions, it makes you feel worse when you satisfy it. That was very surprising to me as a consumer of serial-killer fiction.

J.W.: In the cliché, although you hear it all the time, the neighbor said, “He seemed like the nicest guy.” I think it’s hard to believe, and you also think that’s because the neighbor didn’t know him. But what the research showed was a lot of these guys are oddly successful in the real world. I don’t mean, like, psychopath CEOs — I mean the serial killer who has a job and has friends and is well liked at his place of work and he’s not a split personality; he’s just got both these things inside him. That was very humanizing and interesting. The other thing from the research is the idea that serial killers can exist on a spectrum in terms of their normalcy and that someone could want to get better and struggle.

You mentioned trying to avoid certain tropes but also thinking about the impact it has on an audience to watch someone commit violence. How did you balance that?

J.W.: We were both always remembering what John Landgraf said to us in season one of The Americans, about both violence and sex, which is if you want it to not be gratuitous, it has to come out of and be connected to character. It seemed like we could follow that line here pretty easily.

Obviously, this is a serious show, but there are some moments of levity in it. I laughed very hard when Sam said, “Great. You’ve made me into this guy who buries people in his basement,” but that’s another moment that comes from character and the idea that Sam cannot fully take responsibility for his own behavior.

J.W.: “I’m sorry to give you the bad news that your dad is dead” — that’s my favorite.

J.F.: Everybody’s got a favorite. My favorite is Steve delivering the line “Everyone needs to work on empathy, but you in particular could use growth in this regard.” I mean, there’s no better straight man than Steve Carell, but that’s a really great straight-man delivery.

Did you have Steve in mind for the role when you started writing it?

J.W.: No, not initially.

I know you have been asked this a lot, but obviously Steve is playing a Jewish character and is not himself Jewish. How has the conversation around that casting affected you guys?

J.F.: We get that there’s a conversation there. We get that different people feel different ways. We’re both Jewish, and our Jewish identities are individually very important to us and clearly were very deep influences for us in writing and creating this show. We just felt that finding the best actor for this part was the most important thing, and Steve is that actor. Although this show lives in a lot of specifics about Jewish culture, ultimately what it’s about is, we hope, a universal common humanity, and we think it’s great that we had such a brilliant actor who could help us achieve that common humanity. This is not a story that’s just for Jews by any means. It’s a story for all of us.

J.W.: I think part of our concern is that if we say only a Jewish actor can play this part, then we’re signing up for a lot of other people to say, “Only a Christian actor can play this part,” and therefore the Jews are locked out of that. It doesn’t seem to me like that would be a net gain for the Jewish actor.

My understanding is that the Judaism aspect of this story came a little bit later and you weren’t necessarily thinking about that as a theme until you got more into the project. Is that right?

J.W.: I understand why you think that, because when we tell the story in linear fashion, it did not arrive at the very beginning. But it was soon after. We had this idea for a serial killer who wants to get better, goes into therapy, kidnaps his therapist — and then what do you do? We started talking about the characters and how to make them specific, and it was probably a week after we came up with the original idea that we said, “What if this guy is Jewish?”

J.F.: Very immediately, that came with the story of Ezra and the family divided and how can we explore questions of family and tolerance through that? As soon as we stumbled upon that, it started feeding us a lot of story.

You bring in some Holocaust imagery where Alan imagines himself in Auschwitz. My partial interpretation of that was that it highlights this theme of persecution; Sam seems to feel persecuted, like everybody’s against him. Obviously, persecution is a huge part of the Jewish story, but I also read it as part of Alan feeling like he was being punished for being a bad Jew.

J.F.: Wow.

Did I go too far?

J.F.: That wasn’t in our minds, but — well, it wasn’t in our conscious mind. That’s very interesting.

J.W.: I don’t think we necessarily agreed on all the meanings and everything, but I think we had the same impulse, which is that it seemed obvious to us he would go there. We’re like, “We put a Jew in a basement and make him dig his own grave — he’s going to think about Auschwitz.”

J.F.: The thing that Joe and I really talked actively about was the notion of a Jew — particularly of that generation, but I would scoop us into that generation, and maybe all Jews, really, post-Holocaust — if you’re kidnapped, chained to the floor by a guy who references your Judaism a couple times, no less, and forced to dig a grave, it’s hard to imagine you’re not going to be thinking about that legacy.

J.W.: Just to riff for one second further on your interpretation, it is to a significant degree a story about Alan and his complicated relationship with his son and his effort to repair it. His son makes no bones about saying “You’re bad Jews.” So in a way, maybe it was a wrestling with that, which is essentially what you’re saying.

Yeah, that’s where my thought process around that came from. More than anything, Alan feels like he wasn’t a good enough father, but because of the nature of his conflict with Ezra, I felt like maybe religion was also embedded in that and he was really stung by that comment that he was not a proper Jew.

J.F.: Yeah, I mean, one thing we did talk a fair amount about were these questions of intolerance and his inability to tolerate, accept, who his son was and how those questions swirled through the whole show, really — toward Alan, Sam feeling that way, Ezra feeling that way. They’re all struggling with that.

So it’s time to talk about Sam and his food. How did you come to the idea that he would have a sophisticated kind of palate and love Dunkin’ Donuts?

J.F.: Really, it was — you start out with a character who’s a serial killer, and that’s not that interesting. So then you start talking about their relationships and their family and how they grew up, but you also talk about their lives today. And among the things you go to is, “Well, what do they spend their time with? Do they have any passions? What’s their job? Is it related?” And somehow stumbling into the notion of foodie and restaurant inspector, it gave us a lot of fun dimension.

J.W.: If it’s a serial killer that you’re looking for specificity for, at least for the way we like to write, it’s better if that specificity normalizes them. Everybody I know is either a foodie or surrounded by foodies. It is not an uncommon trait. Even if you’re not one, you can still relate.

But why Dunkin’ Donuts, as opposed to any other coffee?

J.F.: We’re so glad you asked. Dunkin’ is really known for having amazing coffee, and many, many foodies that we know will go out of their way to get Dunkin’ coffee.

J.W.: I should give an important detail for anyone reading this who may rush out to Dunkin’ Donuts: It’s always very fresh because they’re constantly selling coffee, and the No. 1 most important thing for a good cup of coffee is that it was just brewed.

J.F.: It’s what we call a virtuous cycle. It’s really good. Because people think it’s really good, they’re constantly having to make more of it. And the way you have really good coffee is by having it freshly made.

In a similar vein, Sam is obsessed with Kenny Chesney. Why Kenny, as opposed to Blake Shelton or some other country artist or even some other genre?

J.W.: There were two pieces that made it perfect. One was that Kenny has this community of fans, this No Shoes Nation — the idea that Sam would be drawn not just to the music but also to exactly what he can’t quite get and wants, which is human connection in the real world. By the way, if you’re in No Shoes Nation, some of that’s virtual, but also he goes to live concerts and makes friends with people. It just represents exactly what he yearns for. The other reason was just what we said before: It’s the specificity, right?

J.F.: Joe’s a real country-music aficionado. I like music, and I enjoy country music, but I don’t listen to it like Joe does. But it turns out Chesney’s music is fantastically good. There are all kinds of songs Joe sent me that I also keep listening to. So that’s no small thing. And, sure, there are other great artists, but when you have that combination of Sam’s got good taste and there’s community for him to seek out, that seems like a good thing.

J.W.: If you’re a parent and you’re reading this Vulture interview, go on your iTunes or your Spotify or whatever and listen to Kenny’s “There Goes My Life.”

J.F.: But only do it next to a box of tissues.