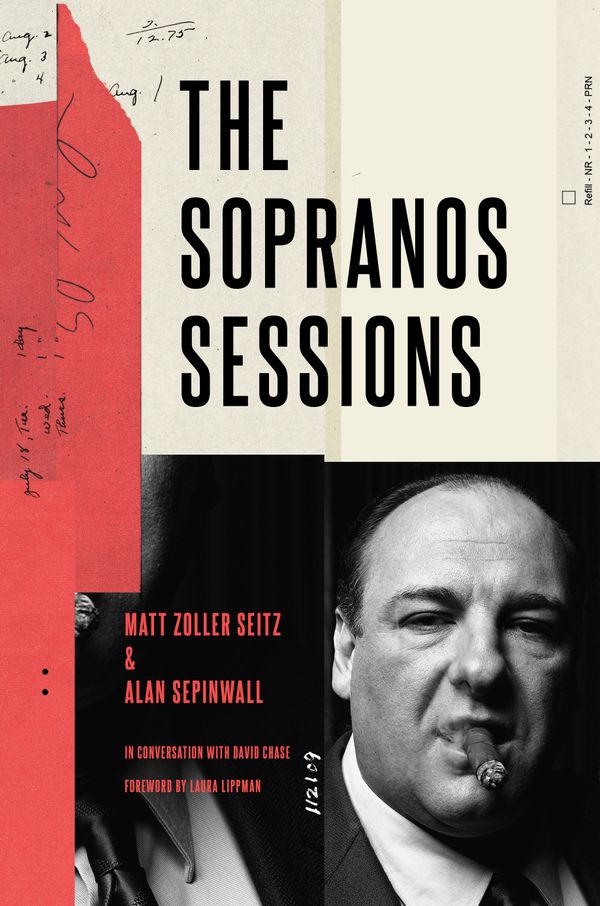

David Chase’s gangster thriller/soap opera/satire/philosophical statement The Sopranos turns 20 today. To commemorate the occasion — ground zero for so-called “prestige TV,” with an ending that people still fight over — I co-wrote a book about it with my good friend, Rolling Stone TV critic Alan Sepinwall, who used to share the TV beat with me at the Star-Ledger of New Jersey, the paper Tony Soprano routinely picked up from the end of his driveway. The book is called The Sopranos Sessions, and it’s available now.

When word got out that our book contained critical essays on all 86 episodes of the series, fans naturally started asking us for our top-ten lists. Mine is below, and Alan published his here. Please share your picks in the comments, or tweet them to me at @mattzollerseitz. (Obviously, this article contains spoilers, so don’t read it if you’re not already conversant with the series.)

10. “Marco Polo” (Season 5, Episode 8)

The Sopranos often had episodes that felt like little self-contained ensemble stage productions, in which the most important action was confined to a single location. To varying degrees, “Pine Barrens” (the woods), “Mrs. and Mrs. John Sacrimoni Request” (a wedding) and “Soprano Home Movies” (Bobby and Janet’s lake house) all fit the bill, but this gem from actor-writer Michael Imperioli and the late, great John Patterson might be the best of them all. It’s the one where Carmela’s dad Hugh insists that she invite her soon-to-be ex-husband to his birthday party. To Carmela’s surprise as well as Tony’s, they end up falling into old rhythms and spending the night together, setting then on the road to reconciling. The serene pacing of the party sequence recalls classics by Robert Altman and Hal Ashby, where the plotting meticulously built towards a predetermined outcome, but it all seemed to happen organically, even randomly, from one moment to the next, because the characters were so finely drawn and the performances so expertly modulated. The secondary plot in this episode is nearly as compelling: Cousin Tony B. (actor-director Steve Buscemi) takes his two sons to the party, and they’re so bowled-over by the Soprano family’s wealth that they make their father feel inadequate and foolish, emotions that lead to his relapse into criminality and, finally, his death.

9. “Made in America” (Season 6, Episode 21)

The only episode besides the pilot that was both written and directed by Chase, this series finale is remembered mainly for its concluding four minutes, a dreamlike dinner with the Soprano family ending in a strangely timed cut to black that inspired debates about whether Tony lived or died and if that question mattered. That sequence alone — an audacious gambit worthy of the 1960s art films Chase adored as a young film student — would be enough to secure it a spot on any list of the greatest finales. But the rest of the episode is remarkable, too. Packing two hours’ worth of incidents into a drum-tight 60 minutes, it’s a corrosive and often haunting examination of impermanence, memory, karma and dread, focusing on a crime family and a blood family reckoning with the implications of their past decisions while facing a cloudy future. It’s also one of the most unnervingly hilarious episodes, mixing absurd-satirical images worthy of Thomas Pynchon or Joseph Heller (A.J. narrowly escaping an exploding SUV while Bob Dylan’s “It’s Alright, Ma, I’m Only Bleeding” plays on the stereo) and subtle bits of character business that, in classic Sopranos tradition, own up to the frustrations that Chase has built into this script and so many others (the mob lawyer Mink keeps whacking that bottle of ketchup, but nothing ever comes out). Chase’s history of challenging and occasionally teasing the fans reaches a giddy zenith here, with onlookers reacting to Phil Leotardo’s gruesome death by staring in goggle-eyed fascination, then getting sick to their stomachs, and the family’s longtime nemesis, FBI Agent Dwight Harris, reacting with delight because he picked Phil to get whacked next in a Sopranos-themed betting pool.

8. “The Test Dream” (Season 5, Episode 11)

The most ambitious dream-driven episode of a series that did many, the Matthew Weiner-written “The Test Dream” is built around a nearly 20-minute, uninterrupted sequence set in Tony Soprano’s slumbering mind. It’s comical, intellectual, and crude, filled with violent, eerie, and lurid images and situations that explore the similarities between dreaming and filmmaking. It weaves in and out of reality so deftly that it’s initially hard to figure out where the “real” leaves off and the imagined begins. It ups the ante on past dream sequences (even season two’s “Funhouse”) by having Tony observe events that are close to things that occurred out in the world while he was dreaming. Merging the conscious and subconscious worlds that the show had kept separate, “The Test Dream” feels like a missing link between season two’s “From Where to Eternity” — in which Chris describes a purgatorial world that he saw while clinically dead, and insists it wasn’t a dream — and season six’s “Join the Club” and “Mayham,” which let Tony wander around in that sort of space, being examined, judged, and challenged, minus the comforts that lucid dreaming provides. The episode also has a guest appearance by Annette Bening as herself, cameos by several deceased characters, and a scene where star James Gandolfini rides a horse through a living room so delicately that you’d think he’d been possessed by the ghost of Roy Rogers.

7. “Second Opinion” (Season 3, Episode 7)

Wherein two main characters, Carmela and Uncle Junior, seek second opinions because they aren’t happy with the first ones. Junior is being treated for cancer, and Tony’s convinced he’s settling for substandard treatment because his oncologist is named John Kennedy. But the more important story is about Carmela. She attends a couples therapy session without Tony, who’s mentally checked out of the marriage, and starts to cry when she tells Dr. Melfi that there’s nothing she can do to heal Tony. Melfi, who’s been pushing Carmela to reckon with her husband’s criminality and her complicity in it, sends her to another therapist, Dr. Krakower. He refuses to allow Carmela to avoid responsibility, warning her that she’s subsisting on blood money and can only save her soul if she leaves Tony and takes nothing with her except her kids. It’s a warning to us as well as Carmela: If you allow yourself to be charmed by these murderous bullies, it’s because some part of you wants to be, and you need to come to terms with it.

6. “The Knight in White Satin Armor” (Season 2, Episode 12)

Directed by Sopranos veteran Alan Taylor (who’s helming the forthcoming prequel film The Many Saints of Newark), this will forever be known as the one where Janice shoots Richie, and it’s one of the most influential episodes of any television show ever made. It taught its contemporaries and successors that you could shock viewers not just with what happened, but how and when. Timing had never before been used as such a devastating dramatic weapon. Most people expected that Tony would kill Richie, personally or by proxy, or perhaps that Richie’s impending marriage to Janice would force Tony to accept him into the family despite hating his guts, setting up another ongoing, slow-burn feud. But it wasn’t just the blindsiding effect of Janice doing the deed that stunned viewers; it was the fact that it happened in the penultimate episode of season two, clearing the deck for one of the most divisive of season finales, the dream-driven, cryptic, scatalogical “Funhouse.” Beyond that, Robin Green and Mitchell Burgess’s script is a masterpiece of construction, setting up that big moment so deftly that you don’t realize until you watch it a second time that it was the only correct outcome, and that the show had spent the preceding 11 episodes building to it. Without this episode, you don’t get the mind-bending twists in the pilots of The Shield and Justified, the death of Rocket Romano on ER, and some of the most wrenching episodes of Deadwood, Lost, and Mad Men, to name just a few classics that learned from Chase and co.

5. “Employee of the Month” (Season 3, Episode 4)

Standing up against its own fan base’s power-fantasy identification with Tony and the gang, as well as four decades’ worth of rape/revenge cliches, this episode gives Dr. Melfi an opportunity to use her scariest patient as a blunt instrument to smash the man who sexually assaulted her. Her decision is expressed in one syllable, “No,” followed by the series’ first-ever cut-to-black ending. It’s a denial of an outcome that the audience, Melfi’s son and ex-husband, and maybe Melfi herself (on some level) all craved. Written, like many classic Sopranos episodes, by Green and Burgess, and directed by Patterson, it stays close to Melfi in nearly every scene, and examines the aftermath of her attack in far greater detail than the attack itself (which lasts about 90 seconds). It’s the ultimate Melfi episode, speaking to the good doctor’s rigorous moral code, which bends but never breaks.

4. “Whitecaps” (Season 4, Episode 13)

Another perfect episode by Green, Burgess, and Patterson, co-written by Chase. Carmela throws Tony out of the house after discovering yet another of his affairs, setting the stage for a series of increasingly raw confrontations between the couple that draw on everything from The Honeymooners to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? It may be the ultimate showcase for James Gandolfini and Edie Falco’s combustible chemistry. And the subplots are strong, too, particular Christopher getting out of rehab, Tony’s escalating tensions with Big Carmine’s New York family, and Tony’s attempt to get the deposit back on the second home he was trying to buy for Carmela, a matter that’s ultimately decided by Dean Martin.

3. “Pine Barrens” (Season 3, Episode 10)

Written by one of the writing staff’s MVPs (and future Boardwalk Empire creator) Terence Winter, and directed by future cast member Steve Buscemi, this is one of the most visually arresting episodes of The Sopranos as well as the funniest and saddest. It’s remembered as the one where Chris and Paulie are hunting in the snowy woods for a Russian gangster they’d tried and failed to kill in order to cover up their own incompetence, but there’s a lot of marvelous housekeeping stuff woven around that, all dealing with Tony’s tendency to shrug off his obligations as a mob boss, husband, father, and boyfriend, and run away before anyone can call him to account. Like other episodes in season three — in particular “Proshai, Livushka,” the one where Livia dies, and “Amour Fou,” the end of Tony and Gloria’s relationship — “Pine Barrens” also intimates that supernatural forces might be afoot in Sopranos-land. But it always stays on the right side of plausible deniability, leaving it up to the viewer to make the case for or against a world beyond the rational.

2. “College” (Season 1, Episode 5)

Written by Chase and James Manos, Jr., and directed by Allen Coulter, this was a medium-altering episode of television. It showed its main character literally dirtying his hands through murder — up till then, Tony had been more of a de-escalator, and somebody who subcontracted the nasty stuff — while touring colleges with his daughter, Meadow. The deft juggling of vendetta and father-daughter slapstick would’ve made the episode stand out regardless, but what makes it an all-time classic is the way it balances the Tony-Meadow story with another two-hander, where Carmela spends a flirtatious but ultimately chaste night with the local priest, Father Phil, and ultimately consummates with him spiritually, through an impromptu confession of her complicity in her husband’s evil. The nerviest creative decision was concentrating on these four main characters and sidelining everyone else, including Chris, who literally phones in his role. It was like a moment in an ensemble play where the stage goes dark and two sets of couples take turns stepping into the spotlight.

1. “University” (Season 3, Episode 6)

The greatest of all Sopranos episodes as well as one of the hardest to watch, this is a level up from its inspiration, “College” (the similar titles cop to the connection). The A-plot is about Tony failing to nurture and protect a naive stripper named Tracee, who’s having an affair with the volatile gangster Ralph, a coked-out bully who ultimately murders her after finding out that she’s pregnant with his child. This horrifying story is juxtaposed with Meadow and her boyfriend Noah breaking up after Meadow’s roommate Caitlin comes between them—not sexually, but by making emotional demands that neither of them are willing or able to meet, and requiring a level of sensitivity to suffering that’s anathema to each of them. Both plotlines are about callousness and dehumanization, illustrating the sickening but very human tendency to decide that other people’s problems have nothing to do with you, then rationalize away the tragic result as a random cosmic dice roll. (In therapy later, Tony decries Tracee’s murder in vague, dissociated terms, changing her gender and calling it a “workplace accident.”) “University” is also an episode that indicts the misogynistic structure of the larger world as well as the insular tribe that is the Mob: Caitlin and Tracee’s stories are mirrors, though the level of physical degradation varies because one young woman is upper-middle class and the other dirt poor. Meadow serves as a rhetorical bridge between all the different moral and philosophical aspects of Terence Winter and Salvatore J. Stabile’s screenplay, variously reminding us of Tracee, Caitlin, Carmela, and Tony. The Kinks song “Living on a Thin Line” comments on the action, appearing three times on the soundtrack and establishing a link between the decay of the Mafia, England, Rome (via Ralphie’s Gladiator fixation), America, and patriarchy itself. The unifying image is the garbage-strewn sewer pipe behind the Bada Bing, reminding us this is a show about waste and wasted potential, and the roles that ideology, greed, and cruelty play in replicating it from one generation and one era to the next.