Is there a show with more friction between the title and the huge name in lights on top of it than Gypsy? There’s a kind of double cosmic irony to the 1959 musical, with its super-singable score by Jule Styne, its zingy lyrics by a young Stephen Sondheim, and its book by Arthur Laurents, still considered one of the very best of its form by people who’ve put in the hours. Ostensibly, Gypsy tells the story — with plenty of theatrical liberties — of its mid-century celebrity namesake, the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee, born in Seattle as Rose Louise Hovick, whose memoirs inspired producer David Merrick and star Ethel Merman to start hunting up writers for a hit. But as anyone passing by the Majestic Theatre today can tell you, top billing never goes to the actor playing her. Louise’s mother — now known to the world as Momma Rose, though onstage, she’s Madam Rose or simply Rose — is the looming peak at the center of the play. It’s the role Frank Rich once compared to King Lear, the blueprint for all complicated, fearsome, possibly sociopathic, indisputably maniacal stage mothers that came in its wake. Fate twists and keeps twisting. If Gypsy is to be believed, Rose Thompson Hovick lived out the tragedy of getting what you wish for: making her daughter shine, only to be eclipsed. But then there was Ethel and Angela and Tyne and Bernadette and Patti and now Audra. Shine out, Rose. It’s your show after all.

At least, it’s certainly Rose’s show right now, in ways both compelling and frustrating. Six-time Tony winner Audra McDonald shoulders the big handbag and small dog as she stomps down the aisle at the top of George C. Wolfe’s revival to thrilled applause, and she earns it — the production as a whole, less convincingly so. It’s not that McDonald’s co-stars can’t run with her; they can, especially Jordan Tyson as Rose’s second daughter, June, the talented “baby” on whom her mother’s hopes for fame and fortune are pinned, and Danny Burstein, who with total ease steps into the slightly shabby three-piece suits of Herbie, the agent who takes on Rose’s act and wishes he could get her heart in the bargain. As Louise, who evolves from wallflower and costume-stitcher to the highest-paid performer in all of burlesque (her claim; the real Gypsy Rose Lee once called herself the “highest paid outdoor entertainer since Cleopatra”), Joy Woods makes a softer impression. It’s a tough role: Again, you’re the title but not quite the star (here, Burstein gets billed before Woods and bows after her, which feels a little off), and you’ve got to play out a long, mostly internal arc, receding for the majority of a three-hour show and then, over the course of a roughly five-minute montage, bursting magnificently and believably into bloom. Woods never quite blows the roof off during her big striptease climax, despite the energies of Santo Loquasto (sets) and Toni-Leslie James (costumes), who cycle her through spangly gowns and Josephine Baker-esque intimates and ultimately surround her with a lavish Garden of Eden diorama that looks like what you’d get if Busby Berkeley hired Henri Rousseau. Instead, her most striking moment is one of her quietest. Much earlier in the show, huddled and spotlit in a corner, Woods sings “Little Lamb,” a sweet, mournful tune that she shares with her stuffed animals when she finds herself forgotten on her birthday. The song is hardly over two minutes long and contains what might be Sondheim’s most earnest and unadorned lyrics, and Woods finds all of its tenderness, beauty, and ache.

It’s moments like this one that throw other aspects of this Gypsy into such strange and discouraging relief. Despite its indestructible book and score and several strong performances, the show Wolfe has built never quite hangs together. Its gestures at times feel stock, at other times scattered, and in much of Wolfe’s work with Loquasto, there’s a sense of getting stuck somewhere between worlds. Is this a scrappy production, or isn’t it? Well, of course it isn’t, but one gets the sense that somewhere along the line, it might secretly have wanted to be. Another irony of Gypsy is that, as a jewel in Broadway’s crown, it’s fundamentally a story of ravenous striving, of having all of the dreams and none of the resources. To the discomfiture of her daughters (played in their younger years by Kyleigh Vickers as Baby Louise and, when I saw the show, the dauntless mini-diva Jade Smith as Baby June), Rose offhandedly eats dog food as the play begins; later, she steals blankets from a bunkhouse to turn into coats and cutlery from a Chinese restaurant because “we need new silverware.” When her girls score an audition at Grantzinger’s Palace, a vaudeville house in New York, the big-cheese producer’s secretary (Mylinda Hull) snarkily informs him that their act is delayed getting started because “they’re having a little difficulty with their scenery.” But then we see the scenery in question — this time, it’s farm-themed, as Rose creates endless variations on the same routine for June and her backup dancers — and it’s sizable and sturdy, unquestionably built in a Broadway scene shop. This isn’t some janky jumble that Rose has hauled cross-country in her beat-up car, then spit shined for performance. When she can’t resist rushing out onto the stage later in the act to point out her own sow’s-ear-to-silk-purse ingenuity — “Woo, woo! Watch this! It’s a train!” she shouts to whoever’s watching from the back of the house — the joke doesn’t really pack a punch because, well, yes, clearly, it’s a train, expensively constructed and moving just like it should.

This stuff matters because it creates a disconnect between the struggle we know Rose and her kids are going through and the relative cushiness and aesthetic predictability of our own experience. Maybe producers worry that if Broadway audiences don’t see a real car roll onstage (one does), they’ll feel as though they’re not getting their money’s worth. But story still has to come first, and the truth of a story like Gypsy’s is that it’s got more in common with Mother Courage and Her Children than it does with the Ziegfeld Follies. It’s not just a showbiz yarn; it’s a story of want and ambition and also, when it comes to Rose, of incredible charisma and creativity, all tangled up with the monomania and narcissism. Indeed, one of my only minor gripes with the show itself has to do with the running gag of the girls’ act: “Extra! Extra! Hey, look at the headline!” sing June’s backup boys (and eventually, Louise’s backup girls) no matter what context Rose has shoehorned them into. The props change, but the act itself never does, which is a good joke and an effective structural choice — and also a little unfair to Rose; I always have to put aside the feeling that she would have thought up something better. Her tragedy is, in part, that the Mr. Grantzingers of the world look down their noses at her, but for us, out in the dark, there should be something awesome about what she’s able to do with two pennies and some stolen forks, even as we can clearly see how threadbare it all is. In Wolfe’s production, I get the sense that scrappiness may have been talked about during the design process, but it and its significance fell by the wayside. The world of dog food and desperation and unpaid rent is too far away.

Bewilderingly, so is the reality of the body. Perhaps most disconcerting of all this Gypsy’s gestures is the fact that once we get to the burlesque section of the show, both Louise and all three of the strippers who befriend and encourage her are wearing visible nude body stockings. Okay, perhaps Louise’s can be overlooked for practical reasons — she does have to make a whole set of slinky quick changes. But for the indomitable Tessie Tura (Lesli Margherita), the brassy Mazeppa (Lili Thomas), and the shamelessly sparkly Electra (Hull again)? Why are we looking at three tummies covered in pantyhose? Isn’t this a play about stripping? Doesn’t our heroine eventually discover her own agency, perhaps even something like joy, by publicly embracing and celebrating her body? Whatever the reasoning here, it’s dispiriting. The strippers are rock-star parts, gloriously unembarrassed, scene-stealers if ever there were any. Are we really so afraid of these actors’ real bodies?

Not only do the costumes for Tessie and her sisters feel like a disservice; the direction they and the majority of the ensemble seem to have received also isn’t doing them any favors. McDonald, Burstein, Woods, and Tyson often feel like they’re inhabiting their own acting island in the show. They’re focused, full of feeling, broad or subtle depending on the need of the moment (McDonald and Burstein are particularly lovely together in their duets), while the performances on all sides of them are distractingly packed with ham. It’s not an individual actor problem; it’s an overarching, miscalculated choice. From Jacob Ming-Trent’s Uncle Jocko to Brittney Johnson’s Agnes (one of the girls Rose takes on to perform with Louise) to Tessie, Mazeppa, and Electra, Wolfe has everyone cranked up to 11. It may be intended as a nod to the show’s vaudeville roots, but the result is that many of Laurents’s jokes, often dry and Groucho-ish, don’t land. They’ve got too much shtick weighing them down. When Hull is playing Mr. Grantzinger’s judgy secretary, Miss Cratchitt, she and June share a run-up to a classic punch line:

CRATCHITT: Say, woman to woman, how old are you?

JUNE: Nine.

CRATCHITT: Nine what?

JUNE: Nine going on ten.

CRATCHITT: How long has this been going on?

Rim shot! But Hull leans so hard into the sarcasm, pressing down with such weight on the word this, that the double meaning of “going on” disappears. Something light and smart is lost, replaced with something bulky and obvious.

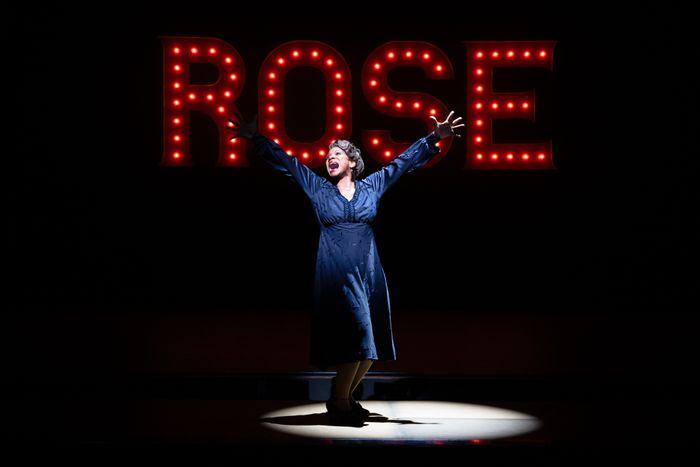

So, out of decidedly mixed surroundings, steps Audra. Perhaps she would generate even more heat, or a different kind of heat, in a sharper, grittier, more deeply realized world, but even so, her gleam is formidable. Fascinating, too: If you’re a Mermanite when it comes to Roses, McDonald’s classically beautiful, honey-golden voice might throw you. There’s no honk or bellow about her. She doesn’t rail; she resonates. But she also acts the pants off the role. She makes clear why Momma Rose has famously traveled through so many types of voices, drawing fans and defenders with every transformation: because truly, the part is a great acting role. You can sing it beautifully or you can sing it ugly, but any way you try it, you’ve got to be able to rip it and the audience to emotional shreds, both in and out of song. When McDonald tears into “Everything’s Coming Up Roses,” the show’s frighteningly upbeat Act One finale, and especially when she arrives at her eleven o’clock number — perhaps the eleven o’clock number to rule them all, the spiky, spiraling “Rose’s Turn” — she gets nasty and furious and brave. She lets ugly and beautiful blend, finding the tears, the snot, the sweat, the mad glint in the eye. In “Everything’s Coming Up Roses,” she nearly crushes Woods in an embrace that’s compelled by forces far removed from love. It’s chilling and invigorating in equal measure.

Though Wolfe hasn’t double underlined it in his production, the reality of McDonald as the first Black Rose on Broadway also finds full manifestation in the complex knot of hurt, defiance, and rage that is her “Rose’s Turn.” It’s impossible not to remember this woman shoving her lighter-skinned, lighter-haired daughter into the spotlight, then smacking a blonde wig on her remaining daughter once the baby runs away — or not to think back, as that happens, to the dance montage in which we watched her girls grow up and simultaneously witnessed the three young Black boys who had been performing with Baby June as her “Newsboys” (Jace Bently, Ethan Joseph, and Jayden Theophile) get switched out without comment for three grown-up white boys, all flashing Colgate smiles. It’s awful to recall the straggling act’s inability to find a booking in Texas and to hear the echo of Rose saying, “They’re too damn un-American down here; that’s the trouble. We better talk about heading up north.” Suddenly, the same words that were always there land as code. Vaudeville may be dying, but that’s no longer the only reason this act is doomed. Wolfe and McDonald don’t have to overstate it: Rose as a Black woman with a Black family and ambitions in a white world accrues a new layer of tragedy and “Rose’s Turn” new layers of both pain and guilt. Wolfe’s Gypsy may flicker, but McDonald glows like a furnace at its center.

Gypsy is at the Majestic Theatre.