Slick back that hair, friends, Tokyo Vice has returned. The sophomore season of the yakuza epic that doubles as an argument for studying abroad displays steady improvement over the first, as the episodes broaden out into more of an ensemble piece while continuing to deliver on its promise of genre delights. But it would be wise to prepare for heartbreak: Given the pints of blood Max has been spilling in recent months, renewal odds aren’t looking too hot. While the series has its admirers (there are dozens of us!), it doesn’t seem to be contributing much to Max’s streaming imperatives in an era of shrinking TV budgets, nor has it attracted much awards hype to warrant shooting in Tokyo, which surely commands a hefty sum. (The White Lotus ended up setting its third season in Thailand instead of Japan for a reason, and that reason is better tax incentives.)

So it’s highly likely this season’s ten episodes are the last we’ll see of Tokyo Vice. We’ll miss it! The series is far from perfect, but it does possess a certain je ne sais quoi that makes it distinct from so many other prestige-y crime dramas. Scholars call this ineffable quality a “vibe,” that little blanket shows can throw over themselves to make them more than the sum of their parts. As a preemptive farewell, here’s an appreciation of a few things contributing to Tokyo Vice’s general vibey-ness that we’ll sorely miss when the show finally gets called up to the seedy nightclub in the sky.

.

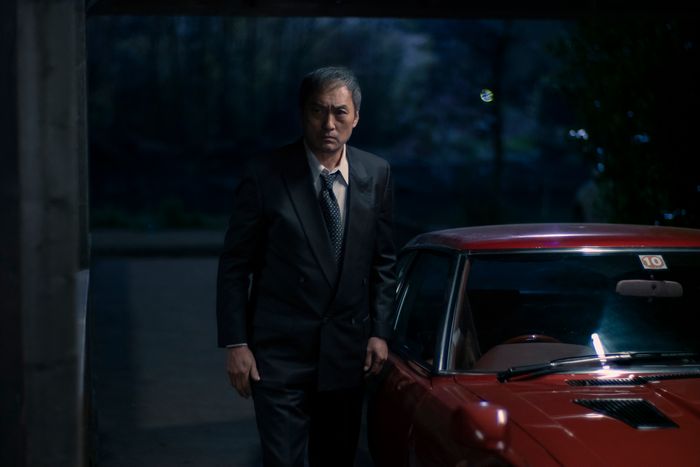

Michael Mann–style Lonely-man Visuals

Nobody conveys “man weighed down by the existential weight of masculinity” like Michael Mann, whose protagonists in Thief, Heat, Miami Vice, Blackhat, and Ferrari are singular figures prone to melancholy staring, weary affect, sly cunning, and an overall exhaustion with the experience of being alive. I love them all! And although Mann’s involvement in Tokyo Vice seems fairly limited (he is an EP and directed the pilot), some of the series’s most evocative visuals are clearly modeled after the chilly, muscular look of his work. The first season included a good number of Neil McCauley–like images of gangsters and cops staring out of windows to get at the idea of criminality as their deadly passion and terrible joy, and season two takes that mentality to other locations: a yakuza walking in a snowy forest, Katagiri hiding in shadows during a police raid. Tokyo Vice is selective with its big action set pieces (and they’re very good, in particular season one’s home invasion and assassination attempt against Chihara-kai oyabun Ishida), so the series’s visual language has become more dominated by these compositions, which reflect the interiority that Mann’s work has always been about. —Roxana Hadadi

.

Surprise Coziness

For a hyperviolent show about organized crime and the dark underbelly of society, Tokyo Vice is an unexpectedly cozy affair. As far as I can tell, only some of the show takes place in the wintertime, but cinematographer John Grillo’s emphasis on keeping things moody and shadowy — even in the daytime! — means there’s ample opportunity for paradoxical hygge. Relentlessly dark rooms are cut by the warm glow of table lamps or comfy side lighting. Tokyo’s neon signs add a dash of East Asian noir to night scenes, but the way their liveliness cuts against the muted blues and grays that paint the rest of the show creates an unexpected feeling of comfort. The wardrobing is a standout in this regard, with sweater vests in particular being the MVPs. Jake’s bald-shaven co-worker Tin Tin (it’s never terribly clear why they’ve stuck to the nickname) is the king of the dweeby but oh-so-cozy sweater vest. And at the end of the second-season premiere, we find Ken Watanabe’s Katagiri breaking into a politician’s house and threatening him with dismemberment while rocking a sick puffer. You can’t extract information without feeling padded, you know? —Nicholas Quah

.

No Reservations

Tokyo Vice is actually a travel show. There’s a touch of anthropological tourism at play with the series’s tumble down the yakuza rabbit hole. As it unspools its story of warring criminal factions, it’s also wandering through a subculture that expresses something intimate to the history of a whole other country. Mostly, though, the travel-show stuff really comes through in the abundance of noshing on display. Food plays a huge world-building role in some of the best HBO dramas. (Yeah yeah, Tokyo Vice is a Max show, but roll with me on this.) Think McNulty and Bunk eating crabs in the evidence room, or Tony Soprano constantly confronting Italian delicacies, or Hot Pie being Game of Thrones’s resident Top Chef. Tokyo Vice operates on that wavelength, too. Decent chunks of the show take place in smoky izakayas and eateries. In the second-season premiere, Jake and his journo-bros are chowing down on an assortment of small plates — I see skewers, tempura, pickled veggies — when they get the call about their office being on fire. The nomming isn’t just limited to restaurants, either: At one point last season, Sato cooks Samantha a tamagoyaki so fine it gives Sydney’s omelet in The Bear a run for its money. Ugh, I’m starving. —NQ

.

Newsroom Drama

Given that the series is born out of Jake Adelstein’s book Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan, it was inevitable that Jake’s time working at the Meicho Shimbun, a thinly fictionalized version of the publication Adelstein actually worked for, would be a major narrative focus. But unlike, say, The Newsroom, Tokyo Vice doesn’t suggest that journalism is the only thing that can keep a society in check. The writers and editors of Meicho Shimbun don’t all agree on the best way to tackle the yakuza, nor are they all objective on the issue, and those differences in opinion make for great tension between Jake and his editor and mentor Emi (Rinko Kikuchi) and the newspaper’s higher levels of power. Tokyo Vice takes time to show the everyday negotiations that occur between Jake and Emi and the sources they need to do their jobs — citizens affected by the yakuza’s shady business practices, cops Katagiri and Miyamoto, club hostesses like Samantha, and of course, the yakuza themselves — and that push-pull contributed to the first season’s immersive pacing. Season two amps this up with a newsroom mole and unexpected friction between Jake and his fellow early-career reporters; plus, no grandiose Aaron Sorkin–written speeches that make me grit my teeth until they crumble into dust! —RH

.

Boy-band Representation

It’s easy to forget that Tokyo Vice is a period piece beginning in 1999, when boy bands were at the height of their power. You simply could not escape Backstreet Boys, ’N Sync, and the competition between them, and it’s frankly delightful that Tokyo Vice doesn’t pretend they weren’t huge international artists with gigantic fanbases. Why wouldn’t the yakuza be into these groups? They were delivering bops! They were popular with women! They were easy to dance to! It’s very fun to watch Jake, Sato, and other yakuza members sing along to “I Want It That Way” and “Tearin’ Up My Heart,” and also unsurprising that these same 20-somethings would find a way to make those tracks a little erotic and a little vulgar. There’s a geeky earnestness to watching these young men drop some of their posturing masculinity and give themselves over to the music, and that lightheartedness makes for a nice balance with the series’s brutality. —RH

.

Recent Retro Tech

In another of the show’s turn-of-the-millennium pleasures, characters rock good ol’ dumbphones and are starting to play around with the World Wide Web, courtesy of then-cutting-edge 56k modems. But given contemporary Japan’s continued usage of what we’d consider retro technology, the line between present and near-present is fairly blurry in a way that lends a fun temporal weirdness to the show. It’s a country where compact-disc sales are still vibrant and retro gaming stores continue to be everywhere. Indeed, few tangible objects on the show actually feel distinct to the place at that time. The elaborate vending machines, a hallmark of Tokyo in the cultural imagination, are as ubiquitous today as they were in the late ’90s and early 2000s. And so when the show cuts to shots of workaday journalists banging away at (beautiful) boxy laptops around the Meicho Shimbun newsroom, it usually takes me a beat to remember, Oh right, MacBook Airs aren’t around yet. That dislocation is terribly entertaining. —NQ

.

Ultraviolent Gangsters Doing Ultraviolent Things

More than 50 years after the release of The Godfather, Francis Ford Coppola’s film and its two sequels still loom large over gangster stories. Unerring loyalty to the family, the collapse of personal relationships at the expense of that loyalty, the sense that no amount of money and power will ever really be enough — that’s all intrinsic to this genre. And without giving too much away about the series’s second season, Tokyo Vice really digs into those archetypes in this set of episodes. There’s a relationship that evokes Vito and Michael’s bond, family dinners converging various yakuza clans to smirk and sneer at each other, shockingly bloody attacks and fights, a destructive arson scene that nods back to the first-season premiere, and grandiose moments of revenge (including a couple moments that nod at another gangster classic, The Departed). The tropes are familiar, even predictable, but Tokyo Vice puts its own moody and stylish spin on them in a way that feels like homage, not mimicry. —RH

.

Hot Gangsters Doing Hot Things

You can see Shun Sugata as Chihara-kai leader Hitoshi Ishida and Show Kasamatsu as Chihara-kai up-and-comer Sato, right? With their magnificent cheekbones, self-assured body language, and smoldering glares? Do I really need to say anything else? —RH

.

Criminal Fits

Yes, the yakuza, as depicted in Tokyo Vice and just about everywhere else, are super scary. Stabby-stabby, lots of blood, very dangerous. But darn if I don’t tip my hat to the fine fits on this show. Those matching white jumpsuits that the lower-ranking yakuza members wear when they’re hanging out in the clubhouse? They look comfy as hell. Later in the second season, we meet a new character who’s all about massive collars and loud shirts that, honestly, totally work. Oyabun Ishida is all about those wide, loose-fitting suits that were so popular in the ’80s they bled straight through to the early 2000s, and again, the fact that it’s supposed to be a period detail flew right over my head because the look would be so hot right now. Sato’s no slouch, either, though it is interesting that his suits are tailored more tightly than his peers’. A pioneer, this guy. —NQ

.

Jake’s Floppy Hair

As depicted in the text, Jake Adelstein is kind of a smarmy doofus. Capable and probably gifted as a reporter, sure, but very much a cad — a white Japanophile unleashed. Nevertheless, in bursts, there’s a charm to this fictional Jake. Part of this is attributable to Ansel Elgort’s derpy performance and gangly height, but the hair is doing most of the work. It’s hard not to clock the oceanic quality of the thing, how it flops around when he’s getting beaten down. It’s the little things that make up a vibe, you know? —NQ