The half-lives of history are, for Japanese novelist Erika Kobayashi, a kind of fixation. Her first book, Madame Curie to ch┼ìshoku o (Breakfast With Madame Curie), published in 2014, follows a time-traveling cat that draws her powers from radiation ÔÇö ÔÇ£a sparkling lightÔÇØ that is simultaneously killing her. The cat encounters Marie Curie and Thomas Edison, mapping her own familyÔÇÖs past alongside the double-edged histories of radiation and electricity. Kobayashi told an interviewer that when she was initially researching the book, she found an old notebook of CurieÔÇÖs in a Tokyo library. She marveled at how, if you held a Geiger counter up to the notebookÔÇÖs cover, the meter still detected radioactive material. ÔÇ£I was so amazed that the vestiges of Madame CurieÔÇÖs touch were still apparent,ÔÇØ she said, ÔÇ£registering readings like nothing had changed.ÔÇØ

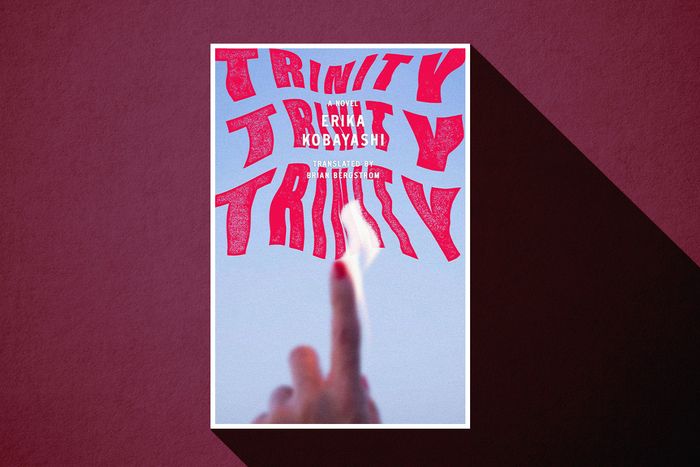

In many ways, KobayashiÔÇÖs second novel, the science fiction thriller Trinity, Trinity, Trinity, is a darker, more elaborate exploration of those same themes. The book, which was released in the U.S. this summer and is KobayashiÔÇÖs first to be translated into English, follows three generations of Japanese women, weaving past and present to explore the personal and collective effects of radiation on contemporary Japan against the backdrop of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Kobayashi first published Trinity in Japan in 2019 and has since said that readers have told her it ÔÇ£struck them as a kind of prophetic workÔÇØ in the wake of COVID-19: Both the Fukushima disaster, which Kobayashi frequently alludes to throughout the novel, and the virus spurred mass paranoia across Japan, and her speculative depiction of the year 2020 through the lens of her narrator ÔÇö reclusive by nature, prickly, anxious ÔÇö grants the novel disturbing retrospective clarity.

Trinity follows the unnamed narrator over the course of one day in Tokyo, where she lives in an apartment with her elderly mother, younger sister, and 13-year-old daughter. ItÔÇÖs the day of the Olympics opening ceremony, and her mother is in the hospital, recovering from a fall. Through flashbacks, we learn that the family only recently moved into an apartment together, and that the narrator and her sister have spent months clearing out their motherÔÇÖs house in the suburbs ÔÇö during which time the narrator began to suspect that her mother, whose dementia has been steadily worsening, might be suffering from a condition called Trinity. Those afflicted become obsessed with radiation, compulsively gathering collections of rocks with trace amounts of radioactive elements and putting ÔÇ£the accursed stones to their ears, listening intently as if to a voice coming from within them.ÔÇØ Among their motherÔÇÖs belongings, the sisters find various pieces of uranium glass tucked deep in a drawer and an old wristwatch belonging to their late father that ÔÇ£glowed fluorescent green.ÔÇØ

Stories of other Trinity sufferers circulate: An old woman who ÔÇ£was rumored to have been discovered with more than ten wristwatches with dials painted with radium paint inserted in her vagina.ÔÇØ The body of another who, when cremated after his death, was said to ÔÇ£have yielded not just ashes and bones when it was burned but melted green glass. It turned out to be uranium glass.ÔÇØ A 91-year-old nicknamed ÔÇ£Radium PrincessÔÇØ by the media hops off a tour bus in Fukushima and runs straight toward the door of a replica of Marie CurieÔÇÖs home (an actual tourist attraction at a Fukushima power plant), waving an ÔÇ£accursed stoneÔÇØ at the guards.

These stories stoke the narratorÔÇÖs paranoia, curdling her otherwise stark narration with incessant flickers of repetition. In Brian BergstromÔÇÖs translation, the phrase unseen force peppers the book. ItÔÇÖs ÔÇ£unseen forcesÔÇØ that unlock the gate as the narrator pays her train fare, and itÔÇÖs an unseen force that raises the televisionÔÇÖs volume as her daughter pushes buttons on the remote. Radiation is, naturally, the novelÔÇÖs most powerful unseen force, and its role as both a curative and toxin exemplifies that of other shared unseen forces ÔÇö including the power of the Olympics as both an emblem of international solidarity and a propaganda machine. Kobayashi references the 1936 Games, held in Nazi Germany, and the 1940 Games, which were going to be held in Tokyo but were canceled as a result of World War II. The 2020 Games, also set to be held in Tokyo, were once again postponed, this time due to COVID-19.

An insidious presence impervious to time, radiation becomes a kind of metonym for history itself as the story unfolds. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs not me who suffers from true memory loss,ÔÇØ reads a tweet written by the Radium Princess. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs all of you ÔÇö you who fail to remember the past, you who cannot feel even the tiniest bit of the pain of that which cannot be seen.ÔÇØ

Kobayashi traces key moments in the history of radiationÔÇÖs global development, narrative slipstreams that perennially trail the present. But the more they multiply, the more these meticulously detailed historical accounts begin to feel impersonal and incidental to the novelÔÇÖs particular fabric. At a certain point, it seems as though Kobayashi is more interested in historical detail than in her own characters, taking care to delineate how the worldÔÇÖs first radium spa was built or to elaborate on an attack carried out by a Palestinian terrorist organization during the 1972 Summer Olympics. The characters, in effect, become subsumed by lengthy digressions and the suspense levels out, then stalls completely.

That disregard for personal narratives may very well be intentional ÔÇö an ode to wider-reaching, conflicting histories. In the early-20th century, radiation was thought to be a preternatural force with the potential to heal and restore. In the years following the U.S.ÔÇÖs bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, thousands of people died from the effects of radiation exposure; other incidents, like the U.S.ÔÇÖs nearby testing of hydrogen bomb Bravo and, later, Fukushima, further compounded those tragedies. To this day, food sold in supermarkets across Japan is regularly tested for traces of radiation, and radiation monitors have been set up in public parks and train stations. Yet the Japanese government along with a number of other countries, including the U.S., have continued to openly expand nuclear power.

ItÔÇÖs this layering that makes KobayashiÔÇÖs otherwise subtle, light-footed writing intriguing. She stacks and Tetrises themes in such a way that their meanings only become clear when seen in relation to one another ÔÇö the Olympics, Nazis, Hiroshima. But often, that clarity feels too hard-won, even irrelevant to the real-time narrative by the time you find it. I found myself thinking, reading Trinity, of the unnamed narrator in Tom McCarthyÔÇÖs Remainder. After an incident in which he loses most of his memory, he becomes consumed with re-creating moments from his past as they come back to him, convinced theyÔÇÖll allow him ÔÇ£to be real ÔÇö to become fluent, natural, to cut out the detour that sweeps us around whatÔÇÖs fundamental to events, preventing us from touching their core: the detour that makes us all secondhand and second-rate.ÔÇØ Kobayashi seems to share that belief, convinced the past is at the core of the present, that the path to true authenticity can only be found through monomaniacal observation. Which would be fine if, by the end of the novel, we believed it too.