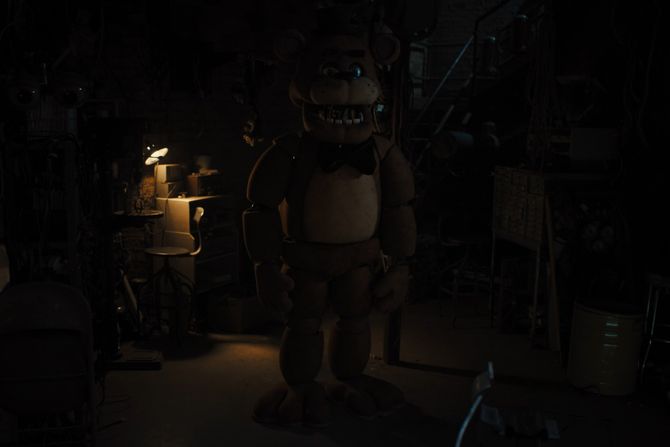

Aside from “Why’s everything so expensive?” the biggest complaint of the streaming era may be “Why’s everything so dark?” The budgets of television shows have skyrocketed in recent years, so why is it often such a struggle to watch them on most people’s screens? It turns out that a number of factors — from the artistic choices (whether they pay off or not) of film and TV makers to the varying technology used to watch their work at home — make it hard to pinpoint exactly why certain scenes don’t always look clear. To better understand this trend, and to drum up some solutions you can actually use, Vulture spoke with four cinematographers whose projects like Five Nights at Freddy’s and House of the Dragon spend long stretches in the dark. They explained why scenes shot in low light can sometimes look so bad that correcting a too-dark screen isn’t always intuitive. Fortunately, they have some tips for that because, like you, they go home for the holidays and adjust their family’s TV settings too.

You all shoot TV shows and movies for a living. Why has TV generally looked darker and darker? Is it a streaming thing?

Shasta Spahn: I don’t know why there’s this trend now to shoot extremely dark, but I think — I’m not going to name names — there are two sides to it. There’s a version where people know what their exposure and balance is and they know how to make a scene look a certain way that has darkness technically. And then there’s the other side of it where people don’t know what they’re doing. They’re making it look really dark. They have no light in the actor’s eyes. They have no separation between the foreground and the background, and it’s unskilled and looks horrible. The sensors on the camera are so sensitive and they have so much latitude now, I would say it’s easy for people who don’t have much experience to go out in the dark and shoot a scene and think they’ve mastered it, but it still requires knowledge of the color-grade scale, exposure, and knowing what your limits are. Night scenes can be done and are done so beautifully, but they’re also done so poorly.

Lyn Moncrief: We live in an era in which people tend to have larger TVs. They tend to have a 16:9 format. We’re no longer in this 4:3 television analog era where the distinctions between television and movies, at least in terms of composition and aspect ratios, are so extreme. Pre-2000, that aspect ratio was forced upon you when shooting TV. Now, I think most — I hate to use the word content — but a lot of projects we see that are streaming only, you could probably project that in cinemas and they’d be just as compelling. You’re seeing a lot more projects, and they’re shooting 2.39:1 with letterboxing and things of that nature that used to always be a fight to have. That cinematic influence has had a direct effect on streaming shows, whereas in the past, that was not the case.

Pepe Avila del Pino: On television shows, particularly in the last three or four years, I’ve seen overprocessed color correction in a way where things look a little milky. The blacks are not blacks. And there’s a standardized look. A lot of TV starts to look the same, and that has to do with many things. One of them is the technology we all have now, like the use of LED lights, which are faster and more practical. The cameras are faster too; the lenses are more sensitive to light. All those reasons tend to push the workflow day-to-day on set with TV on a very rushed schedule, usually. So I think it’s more a consequence of the tools being used, rather than an artistic vision. There’ve been a lot of people making TV very fast in the past few years. Things are pre-produced, produced, and then distributed to postproduction, and then sent back to the streamers in a very short time span. All these factors lend themselves to these low light levels and an overly color-corrected look onscreen.

Aaron Morton: Trust me, it’s gotten a lot better than when I started out. What hasn’t changed is our hope that our intentions from the film set are carried through to the viewer. That’s where we really take responsibility, by being the custodian of those pictures from origination through postproduction to the final viewing. There’s a paranoia, too, because no matter how hard you manage that process, that pipeline, it can go haywire; so many things can go wrong. I totally appreciate the idea that you need to hold its hand through to the final stage. A mate of mine, a mentor, used to say, “Lighting’s never finished. It’s just abandoned.” You can just keep going over every tiny little bit. Part of it is letting go as well.

As a viewer, do you prefer to watch TV or movies a certain way at home?

Spahn: A huge pet peeve is if I’m watching something set at night and everything is so dark. If I can’t see the image in my living room at night with all my lights turned off, then I lose interest and I turn it off. What also really bothers me when I’m watching TV is if I see a reflection of light on the screen.

Moncrief: We converted what was basically a garage into a family viewing room. I don’t know the size of the TV, but it’s quite hefty. We put in surround sound. I like to watch in the best viewing conditions.

Morton: I basically watch everything through my Apple TV. It’s simple. It’s because the Dolby Vision built into Apple TV is a really good — well, it’s an industry standard — viewing platform. I find it’s just really consistent. I never mess with the controls on my TV because I’m always pretty pleased with how it comes up through it.

Avila del Pino: Certain TV brands are better than others, but I think each streamer or broadcasting service has a different compression or a different way of transmitting the image. It’s going to look different for everyone since there are so many variables. I usually watch stuff after the sun goes down unless it’s at the cinema because since I was a kid, in my household, there was no TV before a certain time. I cannot watch things on mobile devices or computers, but I really enjoy watching movies on flights and planes.

How can we best watch stuff on our TVs at home?

Spahn: At home, I really like the original plasma TVs. The blacks are superrich, and the color is very close to what it should be. If you can turn off all the lights, you’ll really get into it. That’s what I do. But I’m also analyzing everything I watch, so I want to see every part of what I’m watching.

Avila del Pino: Definitely after dark with the windows down and the lights off. Well, it’s always good to have one little light, not in front of the screen but a little bit on the side, so you have a sense of perspective and contrast. Being in complete darkness is too much. Oh, and loud sound.

Morton: Look, a dark or dim room — not completely dark, necessarily. Again, I’m not trying to sell Apple, but it does have good consistency and they set your TV up well. Everyone has their own tastes, I suppose.

Moncrief: I still think the viewing experience now is a thousand times better than it was, say, 30 years ago. Everyone’s televisions are pretty good despite the motion smoothing. I go crazy just talking about the motion blur. I have a Samsung, and you go on the menu and you hit “Filmmaker Mode,” which is basically a button to switch to what the filmmakers intended you to see it as. To that point though, there’s not necessarily a standard in which black levels and certain other levels are standardized or regulated. Manufacturers are just trying to sell TVs, so they’re upping the brightness, the contrast, and sharpening. I go over to my parents’ house every winter, and for some reason, the setting always changes. So when I go back, I still have to redo it for them. It is interesting when I ask them, “Do you see a difference?” Instinctually they do, but they don’t really know why or how. It’s the fight of cinematographers and filmmakers to make sure their materials are seen the way they’re intended to be seen.