In 2020, it can be hard to remember how dire the state of American animated television was not so long ago. In the 1980s, repetitive adventure series designed to sell action figures, like Transformers, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, G.I. Joe, and Thundercats, dominated TVs nationwide. Easily the best toons on the tube at the time were reruns of theatrical shorts from the golden age of animation — Looney Tunes, Merrie Melodies, and Tom and Jerry. Even the cream of a new crop of shows, like DuckTales, were reworkings or reboots of long-beloved IP’s, and the bulk of those were clunkers too. (Remember the Ghostbusters animated series? You shouldn’t.)

For some, it seems just as difficult to remember how great cartoons were in the 1990s, when America’s golden age of animated television began in earnest. TV critics gush about Adventure Time, BoJack Horseman, and other shows from the third millennium, but to act as if the new golden age began with these series is to ignore nearly a quarter-century of history that found its genesis in the debut of The Simpsons just a few weeks before the turn of the decade. If there was any uncertainty as to whether this was the first great toon among many and not a one-off deal, the release of the first slate of Nicktoons in 1991 — Doug, The Ren & Stimpy Show, and Rugrats — erased any doubts.

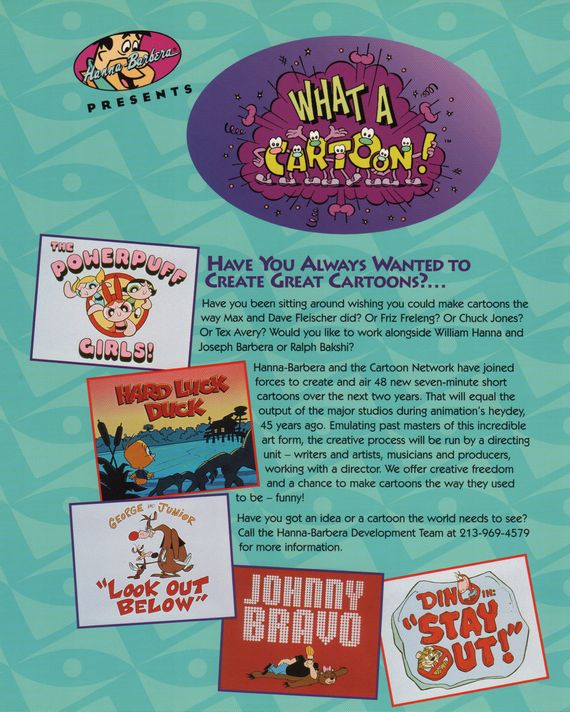

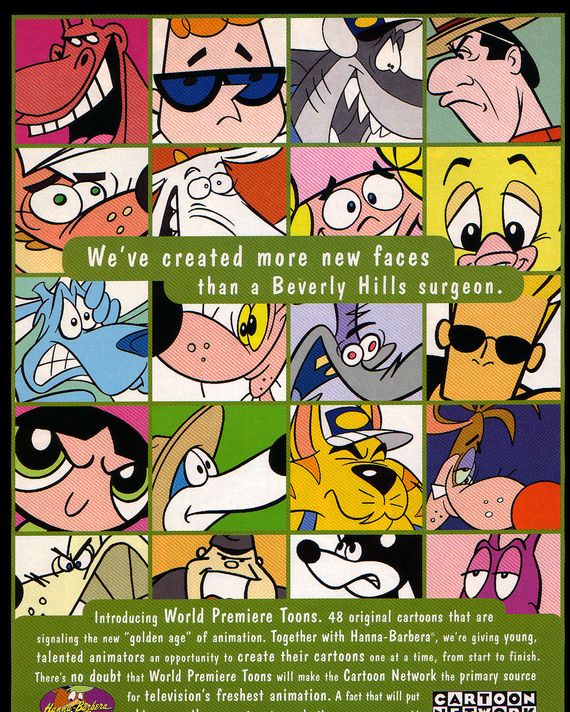

Shortly thereafter, at Hanna-Barbera Productions, a new kind of revolution began to brew: a return to old forms reworked by fresh, new voices. Under the leadership of Fred Seibert — a former ad man tapped by Ted Turner to be president of Hanna-Barbera following Turner’s purchase of the studio in 1991 — a program was launched that would eventually generate 48 creator-driven, seven-minute animations in the vein of the old theatrical shorts from American animation’s first golden age.

Seibert would be the studio’s final president, but the wide-ranging anthology series he developed became an incubator for Hanna-Barbera’s sister company Cartoon Network, which launched in 1992. This series went through a number of name changes after the February 20, 1995, premiere of its first short (The Powerpuff Girls pilot “Meat Fuzzy Lumkins”), being called everything from World Premiere Toons to The What a Cartoon! Show. But to folks there from the beginning, it would always be known as What a Cartoon!

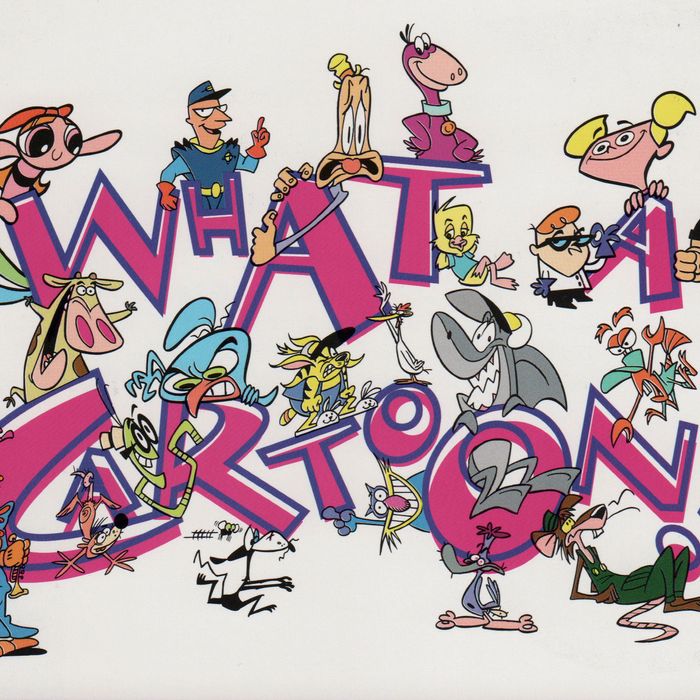

Boundary-pushing but steeped in cartoon history, What a Cartoon! struck a remarkable balance between old and new. It featured work by Hanna-Barbera’s namesakes, William Hanna and Joe Barbera, the Italian animator Bruno Bozzetto, and the adult-oriented independent animated film director Ralph Bakshi, among other old hands. It also launched the careers of a new generation of creators and animators, among them Craig McCracken, Genndy Tartakovsky, Pat Ventura, Van Partible, Butch Hartman, Rob Renzetti, Dave Feiss, Miles Thompson, John R. Dilworth, Zac Moncrief, and Seth MacFarlane.

Of the 18 shorts released in 1995, four were developed into Cartoon Network shows: Tartakovsky’s Dexter’s Laboratory, Feiss’s Cow and Chicken, Partible’s Johnny Bravo, and McCracken’s The Powerpuff Girls. Cow and Chicken would go on to spawn the spinoff I Am Weasel, and Dilworth’s 1996 Courage the Cowardly Dog short “The Chicken From Outer Space” would later be turned into a series as well.

Getting there, though, took some trial and error. When Seibert took over Hanna-Barbera, he says, it was losing $10 million a year, and he had no previous experience with cartoons. He was nervous. But Turner reassured him that it couldn’t get any worse.

“Think about it this way,” Seibert recalls Turner telling him. “They haven’t had a hit since The Smurfs in 1981. If you come in and have a hit, people will think you’re a genius. And if you don’t have a hit, they won’t blame it on you!”

It was a rocky beginning. All Seibert knew when he walked in was that he loved the classic shorts, the kind that Hanna and Barbera, and Warner Bros. before them, had been known for in their Tom and Jerry days. (The kind that, as reruns, made up the bulk of Cartoon Network programming for its first couple of years.) Upon telling his staff about his lack of animation experience, “half of them quit immediately,” Seibert says. And many of those who stayed found his unorthodox methods frustrating — or at least preferred the days when anyone in the office who pitched an idea got the green light and the cash flow to take it to series.

After two swings and misses — SWAT Kats: The Radical Squadron and 2 Stupid Dogs — Seibert became worried. It was 1994, and Nicktoons were firing on all cylinders. So he went to Turner and convinced him to let him start making cartoons “like they used to do in the great days of theatricals,” he says, “one cartoon at a time,” just to see how people liked them. Ten million dollars later, that’s exactly what Seibert did.

Hanna and Barbera, along with Looney Tunes legend Friz Freleng, taught Seibert how the old shorts were produced, and Ren & Stimpy creator John Kricfalusi — now disgraced for his sexually predatory behavior but one of the leading lights of a new generation of animators at the time — advised him as well. Then Seibert opened a call for pitches for what would become What a Cartoon! and in doing so, turned the industry’s established norms upside down: No one would be paid to create storyboards for their pitches, but if those pitches were turned down, the creators, not Hanna-Barbera, would own them.

“The way it worked throughout the ’70s and ’80s was a studio would come up with a cartoon, they would pitch it to a network and then the artists who worked at the studio would make it,” McCracken says. “But in the early ’90s, there was this push: Let’s go directly to the cartoonists who want to make cartoons and have characters and ask them if they’ve got ideas. That’s how 2 Stupid Dogs got into Hanna-Barbera.”

It was also the founding principle of What a Cartoon! At first, the old hands at the studio found this confounding, but the younger generation saw their chance and took it. 2 Stupid Dogs may have been a commercial flop, but it was staffed by a slew of young animators, most of whom were hungry former California Institute of the Arts students — among them, McCracken, Tartakovsky, Hartman, Renzetti, Feiss, Thompson, Moncrief, Paul Rudish, Andrew Stanton, and Conrad Vernon — and all but Stanton and Vernon would go on to be involved with What a Cartoon! Of those, all but Rudish, who was instrumental to both Dexter’s Laboratory and The Powerpuff Girls, pitched their own shorts.

They pitched those shorts to a greenroom full of nearly 20 people, which Seibert had organized because, he says, “I was so scared that I knew nothing.” The room contained representatives of Cartoon Network, such as Mike Lazzo (the network’s original programmer, the creator of Space Ghost Coast to Coast, and, by 1994, its vice-president of programming, who went on to found Adult Swim and finally retired from the company earlier this year), Hanna-Barbera staffers, and What a Cartoon! executive producer Larry Huber, who would serve as a mentor to many of the creators who came up through the program. That greenroom became a hive of cartoon expertise that would determine what a new era of programming would look like — and whether the creators who brought in their pitches would get a chance to be a part of it.

Talking about those early days, the four creators whose shorts ran in 1995 and were eventually adapted into shows — McCracken, Tartakovsky, Partible, and Feiss — describe a studio environment bursting with creative energy, camaraderie, and a genuine dedication to taking risks. Of their shows, three of them (The Powerpuff Girls, Dexter’s Laboratory, and Johnny Bravo) were based on student films made just a few years earlier, and the fourth, Cow and Chicken, started as a bedtime story that Feiss, who was about a decade older than his fellows, had come up with for his daughter.

While The Powerpuff Girls was the last of these shorts to go to series, it was the first to air. In fact, McCracken says he was initially told it would go to series even before What a Cartoon! launched, although that changed once incubating shorts became the priority at Hanna-Barbera. He, Tartakovsky, and Renzetti (who would work on both of their shows before launching My Life As a Teenage Robot at Nickelodeon in 2003) all attended CalArts together. Tartakovsky, the Russian American creator whose Dexter’s Laboratory short “Changes” — adapted from a student film following, appropriately, an extraordinary set of changes — aired only six days later, says their schooling had prompted them to stick together.

“I already lived with Rob in college because we both moved out to L.A. from Chicago, so adding Craig to the mix was very funny,” Tartakovsky says. “Both Rob and I are very independent, and Craig is more of a hang-on kind of guy. If we were ordering dinner, he’d want to jump in. He was almost like our little brother in a way, even though we were just a few years apart — Rob was older than me, and I was a little bit older than Craig — so it was this very funny dynamic. And artistically, we were all very like-minded. We were all supporting each other’s strengths and weaknesses.”

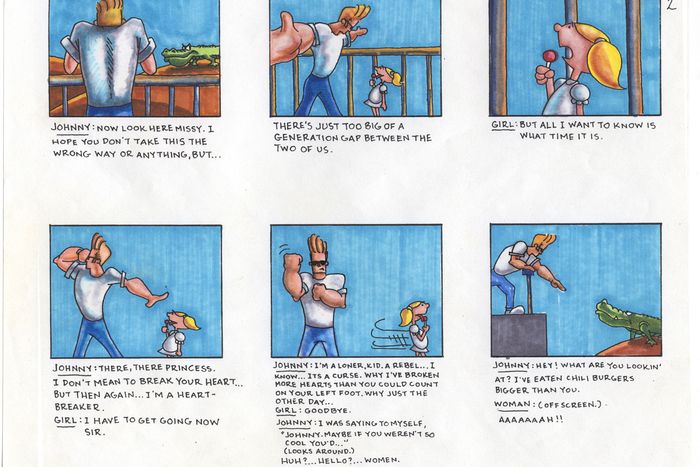

Partible, a Filipino American creator who graduated from Loyola Marymount University, had just turned 23 a few months before the first Johnny Bravo short aired one month after Dexter’s Laboratory. And unlike all the other creators but Feiss, he had every part of his short produced in L.A., including the animation, which then, as now, was usually sent overseas to be completed at a cheaper rate. Another unique thing about Partible’s experience, he says, was the opportunity he had to learn a very new technology: computer animation.

“I was hired at a very low rate to do this short, but because I was getting paid so little and computer animation was just starting up, they said, ‘Hey, why don’t we teach Van how to do computer animation while he’s doing this short?,’” Partible recalls. “So we tried this new system called the Animo animation system and ended up using it to scan all the drawings in and ink and paint them on the computer and then we put them all together. So Johnny Bravo was the first cartoon on TV that was done using a computer.”

Like the other three, Feiss got involved in the industry early. Unlike the other three, he’d been working in it for over a decade by the time the call for What a Cartoon! pitches came around. He had worked at Hanna-Barbera before but was living up in Northern California at that time, working for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. And once he got the go-ahead from Hanna-Barbera to produce the first Cow and Chicken short, Feiss, an animator as well as a director, did something almost no one in the animation industry does: He animated the entire pilot by himself.

“I would work at night animating, and it took ten months to complete the seven-minute pilot,” he recalls. “During that time, I would animate, like, 30 seconds here and 30 seconds there. My art director, who did all the backgrounds, was a guy named Deane Taylor out of Australia. At the time we were doing the Cow and Chicken pilot, he was also working for MGM and he was in Dublin, so he was sending scenes by FedEx to me from Dublin and I was animating them as they arrived.” Although the production was grueling, Feiss says, “it was one of the best times in my career, those ten months. It was the most freeing, creative thing that I had done up to that point.”

The process wasn’t always easy or straightforward. Tartakovsky, McCracken, Feiss, and Partible all mention nerve-wracking focus-group sessions in Dallas and Tucson. While Tartakovsky did well with focus groups, the others weren’t always so lucky, and the lukewarm reception The Powerpuff Girls received was part of what kept McCracken’s short from going to series until two and a half years after Dexter’s Laboratory.

“It didn’t test well. It didn’t test well with boys — and I don’t think it tested that well with anybody — so it didn’t get picked up to go to series at that point,” says Linda Simensky, who came over from Nickelodeon in 1996 and was named senior vice-president of original animation at Cartoon Network and an executive producer on Dexter’s Laboratory. But McCracken’s storyboards for Dexter had won her over, so she advocated for Powerpuff with Mike Lazzo and the original Cartoon Network president, Betty Cohen, but to no avail. “Then I begged Mike: ‘Let’s just let Craig develop it further. He does the funniest boards. I would really like to work with him again, and if we did another show with this team, we could keep them all onboard.’ And of course, we did.”

Hanna-Barbera was throwing a lot of stuff at the wall, and plenty of creators saw their shorts air but go no further. Pat Ventura is a perfect example: An acolyte of Tex Avery, he was the one who first suggested to Seibert that the shorts be seven minutes, à la the old theatrical shorts, rather than a clipped three minutes. Seibert initially saw Ventura as a perfect fit for the program, and in a way he was — he went on to create six What a Cartoon! shorts, more than any other creator. But none were ever green-lit for a series themselves.

Then, of course, there was the gender disparity. Animation has long been something of a boys’ club, but at Nickelodeon, at least Arlene Klasky was a co-creator on Rugrats. All of the 48 What a Cartoon! shorts were created by men. And while some women were involved in the process (Cohen and Simensky, plus Ellen Cockrill, who was a development executive on a number of the shorts, and others) and went on to have fruitful careers on the business side of the industry, and some female artists were also involved, the creative vision was driven by men.

“I think it was just the climate at the time — there weren’t a lot of women who wanted to make cartoons, and if they did, they weren’t getting into CalArts for whatever reason,” McCracken says. “I think there might’ve been four girls in our class. There were women at Hanna-Barbera who were background painters and ink-and-paint people who’d been working there for decades, but it was a bit of a boys’ club. But once we sold Powerpuff, I brought on Cindy Morrow, who I’d gone to CalArts with and was hilarious, as a storyboard artist. And I met Lauren [Faust], my wife, on Powerpuff. She came in on the third season.”

Simensky adds that, while there were a lot of female board artists and a lot of women doing big jobs on the production side, it was difficult to find women creators — partly because of Cartoon Network’s target audience and partly because of the history of animation itself. “I remember taking pitches, and the problem was that Cartoon Network was really geared toward 6- to 12-year-old boys,” she says. “I think at this point in history, there are many more women who can easily create for a larger audience because they grew up with shows that were for more than one gender.”

By the time the last What a Cartoon! short ran on Cartoon Network on November 28, 1997, the American animation landscape had changed for good — and for the better. Long gone were the old days of formulaic, 23-minute action-adventure cartoons. After Turner Broadcasting System and Time Warner merged in 1996, Hanna-Barbera was moved to the Warner Bros. Animation studio, and Seibert left to launch Frederator Studios in 1997, which he just left this year. Frederator went on to partner with Nickelodeon on another anthology series, Oh Yeah! Cartoons, which resulted in hit shows of its own, including Hartman’s The Fairly OddParents and Renzetti’s My Life As a Teenage Robot. A later effort, Pendleton Ward’s first Adventure Time short, would premiere on Nicktoons Network and be anthologized as part of Frederator’s show Random! Cartoons before getting picked up as a series by Cartoon Network and launching a whole new generation of creators itself.

Another Cartoon Network anthology show, The Cartoon Cartoon Show, would replace What a Cartoon! and produce hits of its own, including Hi Hi Puffy AmiYumi, Grim & Evil and its spinoff The Grim Adventures of Billy & Mandy, and Codename: Kids Next Door. Many of these creators and executives would go on to become some of the biggest names in the industry, and some of them are still working today: Simensky is head of content at PBS Kids; Tartakovsky wrapped up his beloved Samurai Jack in 2017 at Lazzo’s Adult Swim and is currently rolling out new episodes of another show, Primal; and McCracken is working on a new show, Kid Cosmic, for Netflix. Even if they aren’t still creating, they set the stage for today’s landscape: Ward’s Adventure Time, Rebecca Sugar’s Steven Universe, and a slew of other hits very well may never have existed had it not been for What a Cartoon!

“This current era of animation was just beginning at that point,” Simensky says. “There was a lot to be learned about how to make cartoons for TV. So we all learned a lot, and those of us who could stayed with it.”

That a program rooted in the history of the art form was so instrumental in pushing it forward only shows how important it was for studios to take chances on creators — to let them, as Partible puts it, “take back our cartoons.” And that’s exactly what they did.