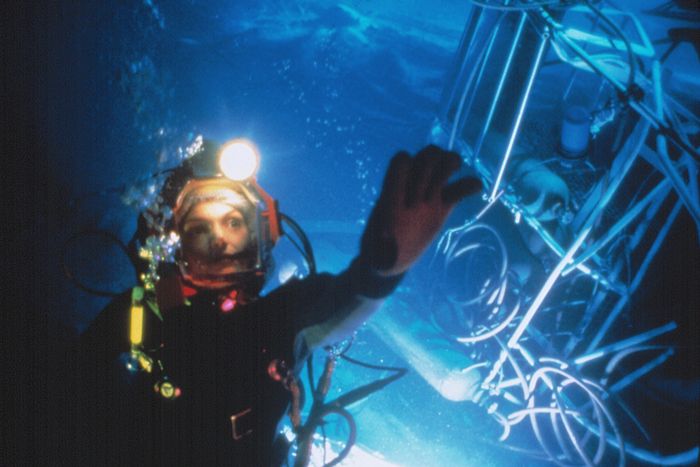

“Welcome to my nightmare!” This was how James Cameron greeted his cast when they first arrived on the Gaffney, South Carolina, set of The Abyss. The director has said that’s how he always welcomes his actors, but in the case of his 1989 film, the salutation happened to be true. By the time the cast arrived, Cameron was already way behind schedule. He had built a massive underwater set in the containment unit of an abandoned nuclear reactor, filling it with 7.5 million gallons of water; he had trained his cast to withstand a shoot that would take place largely underwater, requiring them to be in scuba gear for hours and hours at a time; he was also attempting to revolutionize special effects, with elaborate use of then-nascent, soon-to-be-revolutionary computer-generated imagery (CGI). The Abyss was an unprecedented production, and it came with unprecedented problems.

The nightmare soon became everyone else’s as well: The Abyss wound up being one of the most troubled Hollywood films of all time, nearly killing Cameron and some of his cast in the process. (If you dive nonstop, every day, for months on end, eventually a malfunction will get to you.) The director’s exacting perfectionism didn’t abate due to the underwater nature of the shoot, which in turn drove his actors crazy. “Windows were kicked in, cars were kicked in, people were howling at the moon,” was how actor Michael Biehn, a Cameron regular, described it to the Los Angeles Times. The director himself had little sympathy for his cast at the time. “For every hour they spent trying to figure out what magazine to read we spent an hour at the bottom of the tank breathing compressed air,” he told the New York Times. Elsewhere, he declared, “I shed not one tear for them … Actors are pampered in this country more than [in] any other country in the world.” (Oh, for a return to the days when promotional interviews for big studio flicks could be so candid.)

Beset by delays, The Abyss underperformed financially in the summer of 1989. Most of the press focused on the troubled nature of the shoot. Stars Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio refused to talk about the film until the very last minute, showing up belatedly to the press tour, still clearly traumatized by the whole experience. Reviews were middling. To the average viewer, the whole thing just seemed like a more expensive version of Leviathan and DeepStar Six, two other (cheaper) sci-fi underwater thrillers that had already been rejected by audiences.

After all was said and done, The Abyss probably broke even. But it was supposed to be a hit. It was Twentieth Century Fox’s sole big release that summer, when other studios had such gargantuan successes like Batman, Lethal Weapon 2, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. By contrast, The Abyss didn’t even crack the annual top 20 financially. 1989 set records for the box office, but it wound up being a dismal year for Fox.

The greatness of The Abyss is pretty much undisputed today. It’s one of Cameron’s signature titles. The recent 4K UHD release sold out even before it hit stores. There are even those who will tell you it’s the last good film the director ever made. But it’s also not impossible to see why critics and audiences were perplexed by it 25 years ago. Cameron’s picture is really four movies in one: Two of them are fantastic; one is pretty good; one is basically a catastrophe. All are essential, however, to what makes The Abyss, The Abyss — a work whose imperfections add to its deranged grandeur.

The director had made his name with The Terminator (1984) and Aliens (1986), two sci-fi action films that borrowed more than a little from the horror genre: The Terminator is basically a slasher flick featuring a Teutonic robot from the future; Aliens takes the haunted-house-in-space thrills of the Ridley Scott hit Alien (1979) and turns it into a war movie without skimping on the gore, the suspense, or the jump scares of the original. You can see elements of the horror genre in The Abyss as well, in the way its dramatis personae of wise-ass, working-class drillers and technicians and grunts are beset by a mysterious deep-sea force. Even as we begin to discover that these undersea aliens are mostly benign, Cameron can’t help but continue to shoot the proceedings as if this is a horror movie: The diverse cast seems ripe for being plucked off, the way they were in Alien and Aliens and any number of imitators (including, as it so happens, Leviathan and DeepStar Six). It feels like something awful is about to happen at any given moment, though The Abyss ends without much of a body count — just about everybody lives. This is actually one of the film’s strengths, though at the time it might have struck some as a failing. It uses the cinematic vernacular of horror to tell an essentially hopeful story.

That continuing sense of menace also helps sell, to some extent, the growing paranoia of Lieutenant Hiram Coffey (Biehn), the leader of a team of Navy SEALs who have been sent to the undersea drilling platform Deep Core to retrieve some warheads from the wreckage of an American nuclear sub that’s crashed near the 25,000-foot-deep Cayman Trench. As Coffey becomes more and more unhinged, he takes over the role of the villain from the mostly unseen aliens. (Spoiler alert, in case you haven’t seen The Abyss: He’s the one major character who dies — horribly.)

In future efforts, Cameron would more effectively attack the destructive gung-ho machismo of the military, but here, he’s still just trying on the idea. Coffy is not so much a trigger-happy Cold Warrior as he is a lone wolf who’s losing his mind due to pressure sickness. This in turn makes him more pathetic than menacing — another point in the film’s favor that probably felt like a cop-out to viewers, who expected a bad-ass sci-fi action flick only to have it turn into a more life-scale thriller with a painfully, pitifully human villain.

What works best in The Abyss is its most personal story strand: the tale of an estranged husband and wife thrown together under extraordinary circumstances, who wind up reconciling and saving each other’s lives. As noted in just about every article at the time, Cameron and his wife and producer Gale Anne Hurd were going through a divorce while The Abyss was being made. The director tends to reject such readings, noting that the idea for the story predated his divorce. But that’s not how art works. One would have to be a pretty cold-hearted compartmentalizer (not to mention a shitty filmmaker) to not let important aspects of one’s own emotional inner life seep into the work itself. The broken marriage in The Abyss resounds with spite, resentment, and hurt whenever Bud and Lindsay are together, at least at first. It clearly comes from a very personal place.

The marriage subplot also resonates because it contains the two best performances in Cameron’s filmography. As the gruff, working-class drill-team foreman Bud Brigman, Harris is all grease and rueful competence, while Lindsay Brigman (Mastrantonio) is a type-A businesswoman and engineer who seems to care about nothing but Deep Core, the innovative underwater drilling platform she personally designed. It’s hard to imagine Bud and Lindsay were ever married to each other, but the characters themselves clearly realize this (as does the screenplay), thereby opening a window of imagined personal history that transfixes us. Because they seem so mismatched, we begin to wonder what their life together must have been like.

Their troubled marriage comes alive for us because Harris and Mastrantonio are so good at conveying entire worlds with just a couple of lines of dialogue or, even better, with a single glance. When Bud grunts to one of his underlings, “Get rid of these empty sacks. This place is startin’ to look like my apartment,” we can instantly see in our mind the pigsty he must have moved into after he and Lindsay broke up. Simmering hostility supercharges their increased reliance on each other as Cameron’s story pushes them into more and more extreme situations. If these two can resolve their differences, we figure, then world peace might be possible.

It turns out that’s exactly what the aliens are thinking, too. Which brings us to the one thing in The Abyss that really does not work, and that prompted gales of laughter from the audience I saw it with in 1989. After descending (heroically, magnificently) to the lowest depth of the ocean in order to disable a nuclear warhead, Bud comes face-to-face with a race of glowing purple aliens who have built a huge civilization under the sea. As Alan Silvestri’s orchestral score swells, our hero is taken on a trippy, kaleidoscopic roller-coaster ride through this world and then deposited into a little control room where he’s informed that the aliens, who were apparently planning on destroying the world, decided that there is still hope for humanity after seeing Bud’s reconciliation with Lindsay during his deadly solo descent.

This is a subplot that Cameron cut large chunks of from the film’s release version. Much of it was restored for the longer version later made available on laserdisc and occasional theatrical screenings, all of which helped repair the picture’s reputation over the years. Additionally, the effects work in these sequences wasn’t up to par: The director has said that if he made The Abyss today, this ending would be the only part he’d change — that he’s perfectly satisfied with the rest of the movie but that he’d use CGI to do these scenes differently. Certainly, the VFX here leaves something to be desired. “Its payoff effect looks like a glazed ceramic what’s-it your 11-year-old made in crafts class,” wrote Sheila Benson in the Los Angeles Times.

But that’s not the real reason why this final section doesn’t really work. It’s not about the VFX, nor is it about excised subplots. No, the sensibility here is all wrong. The clichéd miasma of Spielbergian uplift that ends The Abyss doesn’t just feel like it’s coming from another movie, it feels like it’s coming from someone who doesn’t really buy it. Cameron had built up a lot of goodwill in the studio system after Terminator and Aliens to make a statement film, a dream project, but he was still operating in an industry where hope usually meant swoony, sunlit shots of people gazing bright-eyed into the distance. And Cameron just isn’t that kind of guy, at least cinematically speaking. Spielberg does Spielberg best. When other directors try it, they usually embarrass themselves.

It’s not that Cameron is a cynic or a phony. Rather, in his universe, hope comes with a harder edge. In later films, the happy endings are founded on sacrifice and loss: Arnold Schwarzenegger’s T-800 does away with himself (and gets one of the great final good-byes in cinema history) so that humanity can avoid an artificial-intelligence apocalypse in Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991); Jack dies in Titanic so that Rose might live on; Jake Sully and the N’avi survive in Avatar because they lose almost everybody they love and fight back with screaming vengeance; the Sully family in Avatar: The Way of Water (2022) comes together because one of their own is killed. These endings avoid corniness because Cameron builds them on what feels like real loss and grief. For him, hope is the blood-soaked smile you give after life takes its best shot.

One could argue that Bud going down to the lowest reach of the season with little hope of return in The Abyss is the sacrifice that justifies the rosy, redemptive finale. And it is, but that’s part of the problem. To have him (and everyone else) brought back to the surface with a flick of an alien’s wrist doesn’t just ring totally false — especially in a film that strives for such tech-head authenticity otherwise — it also devalues that sacrifice. And it completely betrays the bracing humanity of the rest of the picture.

And yet, I’m not sure I’d want it any other way. Because The Abyss is one of those great, baggy works of art that wind up revealing more about their creators than do their more perfectly calibrated masterpieces. The awkwardness with which its many elements sit together speaks to a filmmaker struggling to break free of his comfort zone, to find a way to express himself in new ways while trying to adhere to the formula of the effects-filled carnival-ride blockbuster. It’s the work of a popular artist trying on the mantle of a personal artist, a mantle that would eventually serve him well. The films to come — like Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Titanic, Avatar — wouldn’t just be movies made by a master action director, they’d be movies unafraid to wear their emotions on their sleeves. In that sense, The Abyss points to the future in more ways than one.