This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

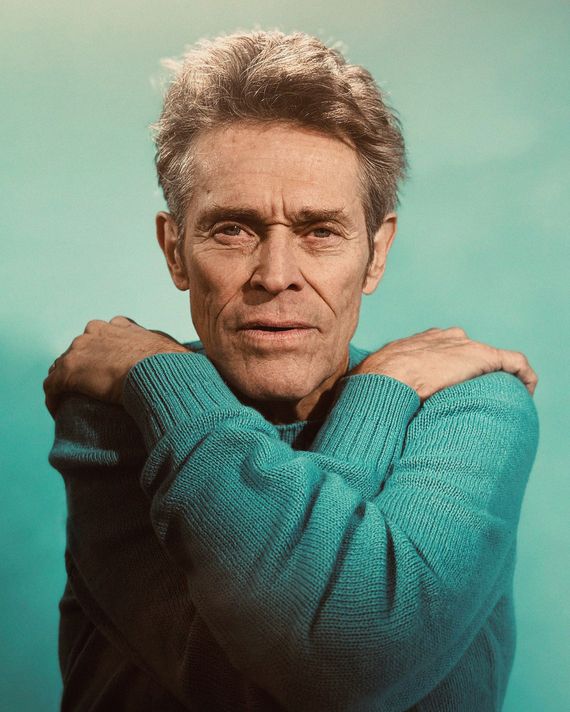

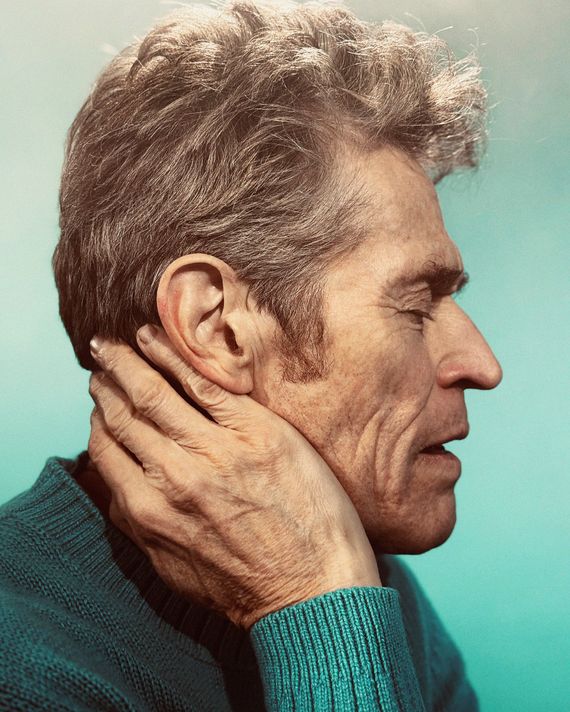

From his earliest credited movie appearance in Kathryn Bigelow’s 1982 biker drama, The Loveless, through his current role in Robert Eggers’s horror epic, Nosferatu, Willem Dafoe has never been one of those “I know that guy!” character actors whose name you have to look up. His slender, angular face is unmistakable. Ditto his gravelly tenor voice, one he’s applied to everything from the enveloping kindness of Jesus and the existential self-awareness of a Vietnam War soldier to the tormented genius of Vincent van Gogh and the chaotic evil of the Green Goblin.

Born in Wisconsin and schooled mainly on the stages of experimental theaters in Milwaukee and then New York City, Dafoe has been a major American screen actor since his performance as a ruthless counterfeiter in William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. Now 69 and with four Oscar nominations under his belt, he’s probably the closest thing modern cinema has to what his Mississippi Burning co-star Gene Hackman was back in the day. Dafoe is also an actor’s actor, respected for the mix of diligence and curiosity that drives his career choices. He takes pride in his public identity as an artist, constantly feeds his imagination with music, literature, and visual art, and goes to new movies not just for the pleasure of immersing himself in other ways of seeing life but to scout new talent (he volunteered himself to Eggers after seeing the filmmaker’s debut The Witch in a theater). Calling from Rome, where he lives part time, Dafoe spoke extemporaneously about the theory and practice of creative work with a plainspoken eloquence that’s rare.

You’re in a unique position, having played a version of Nosferatu in one film, E. Elias Merhige’s Shadow of the Vampire, and the man hunting him in Nosferatu. How would you compare the experiences?

You’re dealing broadly with the same source material, but the impulses are very different. And the nature of being an actor is you do one thing and then you clean it out of your system and get ready to do another, so I have a lot of difficulty putting those two things together. I’m a little in denial! Doing projects, the world’s got to fall away. It’s like falling in love. You can’t be with someone and still be all about your past relationships.

What’s the attraction to Eggers’s work for you? You’ve also been in The Northman and The Lighthouse.

He builds this world that’s so complete, and he’s so committed. He believes we can express what’s going on in this world by reworking the stories of the past. He doesn’t see period films as museum pieces. He doesn’t remind you, “This is such and such a time.” You’re in it. That has a lot to do with his facility with bringing different elements of filmmaking together in a unified way. A lot of directors, to my mind, are a little lopsided in that they’re interested in certain aspects of filmmaking but delegate others. Robert’s hand is in everything. Not that he’s a dictator, but he gets collaborators with whom he has some sort of sympathy and understanding, and they all work together to make this world, so nothing feels uninvested. Everything has a purpose. That means it’s easy for actors to be present in that world, too.

When you’re playing, say, a motel manager in The Florida Project or a drug dealer in Light Sleeper, the characters are earthbound with feelings and needs and circumstances that can easily translate to most viewers. But when you’re playing a vampire or a guy who hunts vampires, what do you do to make the characters feel concrete, plausible?

There’s so much. A great example is any kind of extreme makeup, like I had in Shadow of the Vampire or Poor Things. That was a huge invitation into a world of pretending because you look different, you feel different. If it’s the right mask, it’s liberating. You sit in a chair, and you’re looking in the mirror, and you see your physical appearance change. Sometimes you’re sitting there for hours. At first, it becomes a meditation on what you look like, but that goes away and then all of a sudden you’re looking at someone else you don’t normally see in the mirror, and that allows you permission to inhabit a whole other set of impulses and thoughts. I understood that a little bit when I put in the teeth of Bobby Peru in Wild at Heart and I couldn’t close my mouth.

Speaking of fake teeth, what was the logic in the Spider-Man movies of giving Norman Osborn, a.k.a. the Green Goblin, prosthetic teeth for the “real world” part of the performance but then letting you have your actual teeth for the dreams or hallucinations?

I have spaces in my teeth. They aren’t perfect. They haven’t been fixed. They’re a little funky. I don’t mind them. One of the producers on Spider-Man said, “Well, aren’t we going to do something with the teeth? It’s not credible that a CEO would have teeth like that,” which I thought was very funny. The compromise was we decided to put these caps on my teeth so I would look like a guy who was groomed to be a CEO and then when I was the Green Goblin, which is kind of the true self, I had my regular teeth.

Have you ever been urged to Hollywood-ify your face, do Botox, get veneers or anything like that for career reasons?

Not at all. They aren’t looking for Hollywood smiles when they cast me. That’s never been an issue. I’ve got an expressive face, so leave it alone.

Are you familiar with the Willem Dafoe memes circulating around the internet? The Lighthouse Keeper shows up a lot, and of course Norman Osborne saying “I’m a bit of a scientist myself,” but with “scientist” swapped out for some other job or specialty.

I try to avoid these things, but some of them catch up with me. Usually I’m pretty amused by it. I had a wonderful time being in The Lighthouse. It is probably not wise to say you like your movies, but I like that movie.

Why is it not wise to say that you like your movies?

In the same way that it’s not wise to say you don’t like your movies. Leave yourself out of it! I’m doing press right now. I’m talking to you. In a perfect world, you wouldn’t know anything about me. You wouldn’t know where I live. You wouldn’t know where I come from. I’d just be this guy that becomes these other people. All this extra information about the actors, about the production, about the cost, about the expectations in relation to budget — all that stuff doesn’t really help the way I see cinema.

I feel like the relationship of the audience to movies has changed in the past ten or 15 years. They expect the movie to come to them.

Absolutely. They’d rather go home and turn on their TV and see a film that way. And let’s face it, a certain kind of corruption comes in because people go home and they shop around on these streaming platforms. There’s some good things about the platforms. They create a lot of movies. They create a lot of jobs. But there’s so many distractions that you can’t enter the stuff. People watch five minutes of something and they say, “I’m not really into it” and they go to another thing. “I’m not really into it.” Then another thing. “I’m not really into it.” Then they go to bed.

If you don’t put in the effort, you’re not going to receive much. And the discourse gets lowered, and everything gets a little more dumbed down and then that’s when the ruffians come in, and they’re the ones with energy and stupidity and then they can crush all the thoughtful people. That’s not good for culture, and that’s not good for humanity. We see the results of that all the time.

Who were the actors who spoke to you when you were coming up?

I went through a period where I liked actors who I thought weren’t actors.

Like who?

Oh, people like Warren Oates and Harry Dean Stanton. When I found out they studied to be actors, I was like, Damn. They’re good. Those guys didn’t have that stink of being an actor. Not even a little bit. When I was really little, I grew up on horror films. I thought Boris Karloff was fantastic. I thought Vincent Price was a hoot. I never had that kind of Monty Clift–Marlon Brando thing.

Marlon Brando was always interesting, often so interesting that he was sometimes not quite in the movie that he was in, if that makes any sense.

Very true. Something to posit: Is it possible for there to be a good performance in a bad movie? Because, well, what are you cutting up responsibility for? The film is a whole thing. So how can it be a good performance if it doesn’t serve the movie?

I’ve seen lots of good performances in bad movies, though. One can’t know what happened on set to allow such a thing. And I wonder, Did that one actor who was good just have the willpower to stand against whatever bad notes everyone else was getting?

Okay, okay, okay: You realize that notes are, like, a myth? Practically.

What do you mean?

People think directors pull actors aside and have little conferences and then they say, “Go again.” It’s not like that. Or not in my experience. We have little conferences about the psychological aspects. It’s much more practical. But maybe that’s me. Maybe they just let me go!

You’re telling me you’ve never had an experience where you were being strongly pushed to give a particular type of performance, and you drew a line in the sand and said, “Nope. I’m doing this other thing”?

Never. I don’t think ever. I’ve been annoyed sometimes when someone pushes me in a direction I don’t feel comfortable with. But — not to make it sound like I don’t have a will — I generally try to find a different way to satisfy them, one that also satisfies me. Then I get there and I try to give myself over to the actions. And something happens. That’s the beautiful thing about making movies. They have their own life. They come alive or they die, but they shift. And you have to be sensitive to that.

You surrender to the process.

Yes. I think it’s the only way. Surrender means forgetting yourself and trying to see another point of view, or trying to see another way, or trying to have different impulses and feelings and experiences.

You have been in a lot of films that are like that: gateways to experiencing an alternative way of seeing things.

Which is the best a culture can do.

Do you seek out filmmakers who try to do that?

Projects find you, and you find projects. I sought Wes Anderson out. I invited him to a theater performance of the Wooster Group. He came. We had a beautiful dinner. He said, “I’d love to do something with you, but I’m going off to Italy to do this film, and it’s already cast. So maybe I’ll see you in five years.” About three months later, I got a call. Wes said, “Someone dropped out, and there’s a role I’d like you to do.” So I went and I did that movie, The Life Aquatic, and not only was it great fun and my introduction to Wes, it’s how I met my wife.

For Wes Anderson, you’ve played a lot of what I would call commando supporting roles, where you kind of parachute in and make a strong impression in a few scenes, like the dancing rat with the switchblade in The Fantastic Mr. Fox, the bookkeeper in The French Dispatch, and the assassin in The Grand Budapest Hotel. What itch does that scratch for you?

I just like being in his company. He’s such a master at what he does; he gets more articulate and powerful with each film. It’s fun to be in his world because the sensibility is very precise.

Klaus in The Life Aquatic is one of my favorite roles of yours, because if I were going to predict what character Willem Dafoe would play in that movie, based solely on reading a summary, it wouldn’t have been that guy.

I loved that he was a blowhard German. Klaus exposed the myth of German efficiency and strength. Now I’m going to get hate mail from German people!

Well, we wouldn’t want that! But I know what you mean.

We’ve got to debunk these myths. That’s what will make us all kumbaya together.

You started your career in experimental theater at the Wooster Group, which you co-founded in 1980. How did that inform your approach to your craft, and to what extent has that experience continued to resonate?

It was everything. It formed me in many ways. The most basic thing is it reminded me that the technicians and the actors are almost interchangeable. The technicians would also do acting functions, and the actors would do technical functions.

How did your relationship with Elizabeth LeCompte, the Wooster Group’s director and your former partner, shape you as an artist?

Liz is a great director. She is very idiosyncratic, but I always had great admiration for her commitment and her patience and tenacity. Characters were revealed through actions, not so much through an interpretation of literature or designing a psychology that would convey to the audience something about human nature. It always felt closer to dance for me. It was about doing things, and as you did them, things would happen to you. I am not really a director type of personality. I didn’t want to watch things. I wanted to be things.

I’ve been to Japan quite a few times, and when I go to the theater there, particularly the Noh theater, I get terribly moved by those performers because there’s a whole life, a history, a commitment to the gesture, to a kind of tradition. That might sound rigid, but it’s not, because what I see is a human being living and dying onstage. You see that in dance. You see a body out there moving in time, and I like being there for that. Whether I’m an audience member or I’m an actor, I like to find that sweet spot that is free of a transactional or egotistical kind of thing.

Man, you’re speaking right to my heart here.

Well, take care of it because I’m sticking my neck out!

“Commitment to the gesture” is a great phrase.

I’m not Catholic, and I’m not totally down with organized religion, but I respect and am interested in the spiritual impulse in the human being and how it forms. When I’m at Santa Maria Maggiore and I see all these old people participating in these rituals that they’ve done over and over again, I get moved, because I feel like I’ve got my finger on the beauty and tragedy of our lives.

You left the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee after two years and joined an experimental theater troupe in Milwaukee, then went to New York soon after that. Why didn’t you finish your degree?

I had ants in my pants. I was a young man and I wanted to get out in the world. I came from the Midwest in a town of 50,000 people. A perfectly good way to grow up, but I felt like there was something out there that I needed to see and become. I just wanted to start doing. That’s something you could do in a time when a kind of amateur aesthetic was being embraced. When I came to New York, there wasn’t so much emphasis put on professionalism as it was the sincerity and the will of this person to get up and perform. Were they trained for that? No. Was it a career aspiration? It was an extension of their lives. Being around these artists was infectious. And when I was young, particularly, I flirted with this idea of being an artist rather than thinking about a career and making money.

Having said that, I’ve never been interested in exposing myself in the way a lot of them did, because if you make it about you, you’re limited. You have to make it about other people and go toward that. That broadens you and makes you more alive and in tune with the audience, rather than getting in front of people and dazzling them with a skill. I would go home for the holidays when I was young with all my brothers and sisters, and they were far more talented than me. I’m not being falsely modest or anything. I had a different intention from them. They could sing, dance, they could all do all these things, and I could do some of that, but the thing I was really interested in was trying to give myself to something and lose myself in it.

You stuck with the Wooster Group all the way through the early aughts. Why did you part ways?

As I started doing movies, I started being away more. Since we were making original work at Wooster Group, there was a real tension. I’d be gone, and they would either have to minimize my involvement or they’d have to wait for me. Neither was a healthy solution for the company. And then there were some changes in personal things.

You made your film debut in 1980 in Heaven’s Gate, but what put you on the map was William Friedkin’s 1985 film, To Live and Die in L.A. You played a counterfeiter named Rick Masters who is being chased by Secret Service agents. What was that like?

It was fantastic because William was on fire. He wanted to make a movie that was down and dirty. When he first met me, he said, “Listen, I want to get a bunch of unknown actors to make this thing.” He was game. And every day there was some big surprise. Sometimes you’d get to the set and he was like, “We’re not doing that at all. We’re going to do this.” You always had to be on your feet.

Did you know that after it came out, he was using the prop money you used on set to buy things? Because late in his life, he admitted that he had done that.

What do you mean? [Laughs] I made the counterfeit money! You see it in the movie! If you think people didn’t maybe put one in their pocket to see if they could pass it … But, don’t get me arrested! That was a long time ago.

I hear so many wild stories about Friedkin. Is it true that he would roll film without telling the actors he was rolling?

I’m sure, but a lot of people do that.

What does that accomplish?

It gets something that’s not premeditated. If theater is about conjuring and cinema is about capturing a performance, you can catch some interesting things working that way.

Is it true that you were considered for the Joker in Tim Burton’s version of Batman?

All I know is at one point, one of the people who was involved with the comics suggested that I might be good for the Joker, and somehow that got into the press. But no, I was never offered it. But at that point, I was on some kind of list to play Batman. Don’t fucking make that face!

No! [Laughs.] I’m just reacting to not having heard that before. I love the idea. I was reading The Dark Knight and The Killing Joke and all those kinds of harder interpretations of Batman that came out in the ’80s, and I think you would’ve been a great Batman in a story like that.

Yeah? Okay. Well, thank you. But that’s just not the way it goes.

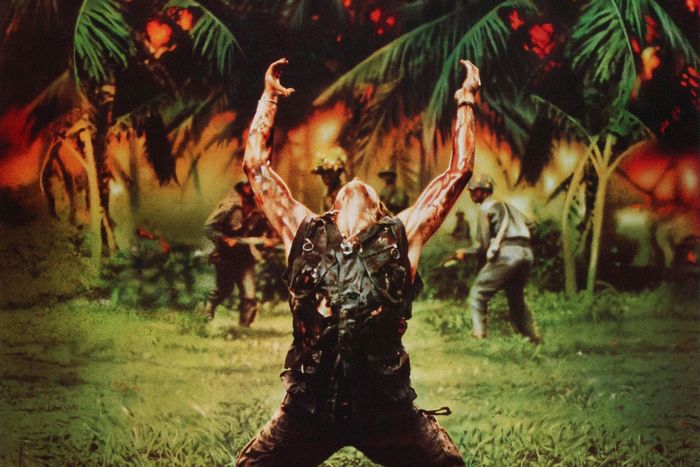

I want to talk to you about what I think of as your Jesus trilogy. In 1986, you played a saintly martyr in Platoon for Oliver Stone, then Jesus for Martin Scorsese in 1988’s The Last Temptation of Christ. A year later, you’re in Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July mentoring another martyr, Tom Cruise’s Ron Kovic. You’re on the poster for Platoon: a crucifixion on a Vietnam battlefield.

Platoon was an actor’s dream in the sense that it was a very simple action scene. So my body is rigged with squibs, these little explosive hits they used in the old days. Now, they tend to do these effects more in postproduction, but I had actual wires going around my body, anchored in the ground. There are all these explosions. I know where they are. I’m at the edge of a clearing in the jungle, and there are hundreds of extras behind me. The camera crew is up in the air in helicopters, and they’ve got some cameras running remotely in the ground, and my action is the simplest one in the world: Run for your life. It’s so emblematic of the tragedy of the personal, bodily destruction of war. Oliver gets credit for that because he puts all those elements together, but I won’t be shy: I’m there for it. My cheekbone, my body, the way I raise my hands, the uniform, the extras behind me, the green, the explosions: It’s a big soup, and I’m just trying to be the best carrot I can be in that soup.

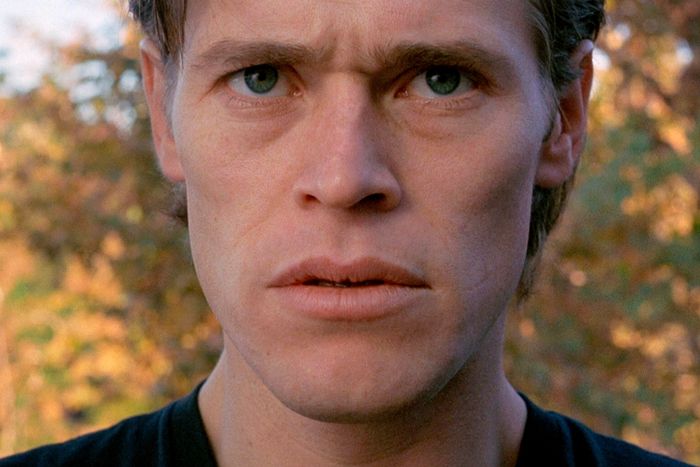

It’s an interesting progression for you during that period because you had made such a big splash as the bad guy in To Live and Die in L.A. and then you’re in three major films focusing on martyrdom.

Masters, my character in To Live and Die in L.A., was not a good guy, but he had his code. I want to remind you, also, that To Live and Die in L.A. was only successful in retrospect, and it was made successful by cinephiles. But it was the first film I did that really got seen internationally. I’ve been told secondhand that something in that performance was responsible for me getting the role in Platoon and also in Last Temptation.

It’s nice to play a martyr. It’s nice to have strong actions. It’s nice to be against the current. But we’re talking about things that happened 30 years ago. I am much more interested in recent things. You can tell when people stopped or started watching movies or—I’m not pointing at you—the movies they’re interested in. I’ve been doing this long enough that I can always tell when people talk to me what part of their lives they were watching movies in. When people want to talk about the movies of the ’80s and they don’t get to some of the really interesting ones later, I feel funny.

Yes. But you’re one of the greats. I don’t know if you are willing to accept that description, but you’ve been around forever and a day, and the early work is as meaningful to people as the good work you’ve done recently.

I’ll take a compliment because it gives you energy, it doesn’t make you cynical. That’s one of the reasons I like working with young actors, with people who aren’t cynical. They think they’re having the time of their life! What’s hard sometimes is when you work with people who think the good times are over and everything’s a grind now. Some people my age that have been at it for a while lack a certain kind of energy, a kind of a belief. But okay, let’s talk about whatever you guide us to.

You bring yourself to every role you play, but I wonder if you bring more of yourself to roles in smaller-scale films? Does that seem fair?

I think that’s fair. For bigger movies, because there’s more financial investment, people have to be a little more sure, so there’s a tendency to have you do that thing they know you can do or to work that persona or that perception of who you are. Whereas in a smaller movie, sometimes you’re encouraged to do just the opposite, to shake that and create a new self. But if you said all that to a studio executive, they might break into a sweat.

I appreciate the sensitivity and intelligence you bring to everything you do, even if it’s material that’s dismissed as bubblegum. The Green Goblin is an example. You play that role like it’s Macbeth.

It is! You have to remember we’ve gotten used to these Marvel movies and comic-book movies because there are a lot of them. But when we did the original Spider-Man, it was new territory. So for me, it was exciting, and for Sam Raimi to be so passionate about it made a huge difference. I got to do a lot of fun things. It’s fun to fly around. It’s fun to fight. It’s fun to careen from comedy to drama in a second. That’s fertile territory when you’re dealing with questions of morality and good and bad. You can bait and switch. You can play and then get serious. You can turn it on its head.

Has there ever been a performance you gave where you saw the finished film and you were surprised by what you were doing?

Not so much. Because when I see a film, I have strong associations with the making of the movie. And I like movies best when they look like they felt when I was making them. Sometimes you’re surprised by the finished movie if you worked with a lot of variation in the scenes or different takes — if that was encouraged. It’s a little dangerous sometimes to give lots of variations. [Pauses.] Sometimes you’ll be surprised by the editing: by the selection, by what modes they went with. It’s an editor’s medium. You got to give ’em the stuff to work with. That’s why the most important thing for an actor is everything should be played for keeps. So no matter how it gets put on its head, colored, cut, what music’s on it, it has an integrity. That’s when I can live with anything, because I’ve given myself to it in a way that’s not anticipating the result.

Lars von Trier. What about him synced up with you?

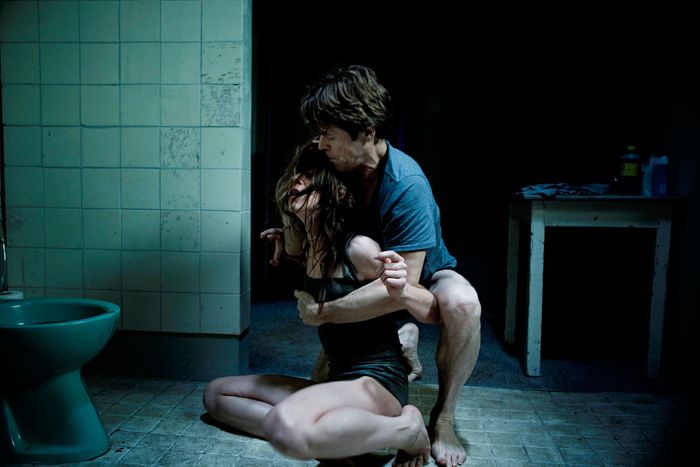

He knows how to speak about the unspeakable. The opening and ending of Antichrist, that’s great cinema. He has his missteps, but I find him very engaging, and he’s a guy who’s committed to searching. Everybody thinks he’s just a wise guy. It’s funny that people sometimes talk about his films being misogynist. He identifies with the women characters, and he’s telling their stories because he’s trying to figure something out. In Antichrist, he’s dealing with themes that some people can’t even go near: men’s fear of women, women’s sexuality, women’s power. All these things that are scary stuff. That’s the whole point — to take away the fear, to get us away from being so blocked, because we try to protect ourselves from these existential fears.

You’re living in Rome these days, right?

Outside of Rome, yes. I’ve bumped around a lot, and I keep the place in New York. But I started having a place here 20 years ago. I tend to split my time between Rome and New York. They’re complimentary cities, in a funny way.

Does your friendship and collaboration with Abel Ferrara, who moved to Rome over 20 years ago, play into your fondness for the city? You’ve done six movies with him over a 24-year period.

Sure, sure. That’s not why I’m here, but that’s one of the benefits of being here. Have you seen a lot of the times we’ve worked together?

Yes. Tommaso is my favorite, about an actor and filmmaker who’s in recovery and fighting different kinds of temptations. I guess you’re playing a hybrid of yourself and Abel?

That was an engaging movie to do because it was really improvised. Sometimes that’s a nightmare because actors have to become writers on their feet. But this was a case of inventing things while not really inventing things. Abel would tell me something that happened, or something he wanted to see, and then we’d do the scene without any rehearsal and shoot it very quickly. They were all things that I was familiar with and he was familiar with. So we had a kind of authority in the pretending, and while the result has some rough elements to it, it was quite unselfconscious.

Both the character of Tommaso and the filmmaker he’s partly based on have been in recovery for a long time. What is the difference between working with Abel Ferrara sober versus not sober?

Well, the joke is not much. I don’t want to not encourage people to get clean. I think it’s a good thing to do. But personalitywise, Abel is very similar to how he used to be, but because he doesn’t have that devotion to something that’s not on set, it makes him more concentrated.

The movies seem to have a different energy. They’re more contemplative and focused.

Not only has Abel become clean, he’s also taken refuge: He’s a Buddhist. I don’t mean to be glib by saying he hasn’t changed. My point is he still has the same manic energy. Sometimes he encourages a kind of chaos that he’s able to funnel into creativity. And often we’re working with very minimal budgets, so you have to really be light on your feet. Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee!

You always seem to be having so much fun, whether you’re acting in a scene or sitting for an interview. Even when I see you on a red carpet answering some pretty light or silly questions, you have a smile on your face. I wonder: Is he that happy all the time, or is he just a good actor?Listen, I’m social. I like people. I see things sometimes as a game, in a beautiful way. If you think about where we come from and think about where we’re going, that’s the reality: All this part, this life part, has got to be, on some level, a game. Don’t get me wrong: I’m disciplined. I’m conscientious, probably to a fault. I could probably even be looser. I’m a worker. But on some level, when I’m in the middle of it, I have these pinch-myself moments that put me in kind of a giddy mood. I can’t help it. You hate to hear people brag about how much they love what they do, but it is that old thing: Love many things, and the more you do things with love, the more beautiful they’re going to be.

That’s nicely put.

I mean, that’s a clumsy rip-off of a beautiful van Gogh quote that I don’t have up my sleeve right now.

I’ve done a lot of interviews with actors in which they seem to denigrate their profession to some degree. I’ve never seen you do that.

Acting can be stupid. It can be selfish; it can be narcissistic. It can be all kinds of things. But it also can be a very fine way to learn how to live and to try to be useful and to put yourself in a situation that other people may relate to.

When do you just sit at home? When do you just relax?

Something I got from my parents is there was a very thin line between their personal life and what they did. One rolls into the other for me. Being with the Wooster Group for all those years, there was a thin line between the personal and the work life. I like that I don’t separate it out. And obviously I like what I do, so I’m always preparing for things or imagining things or trying to set up things. I do many things besides movies.

Do you meditate?

Yes, but that’s not my main thing. I do physical practice every day.

Is it yoga? When I saw you doing yoga in Tommaso, I thought, This is a man who really does yoga.

I’ve been doing yoga for 35 years. It’s a spiritual practice as well as a physical one.

Do you paint or do any kind of visual art?

I’ve always liked to draw, and while I’m not a painter, I enjoy painting. In the case of Eternity’s Gate, I had a very good painting teacher in Julian Schnabel, the director. When we started, he had me look at a tree, and he said, “Paint the light, don’t think of rushing to paint the tree. Paint what you see. You make a mark and then you make another mark, and you see them turn into something.” It’s not a representation of the tree. It’s an expression of what you see. That keys you into the interplay of things. And when you become sensitive to that, it makes you more flexible in your thinking, so you’re not always going for that pure utility of things. Right now, I’m looking at a bag of walnuts, and if I apply what I just told you to looking at that bag of walnuts, I’d have a different appreciation of them. Walnuts are not just something that you eat. I can see the whole world in those walnuts.

Does the word realism have any meaning to you as an actor?

No. When you say realism, I think of naturalism, and I think about natural acting. And when I think about natural acting, I think about natural behavior. And I think sometimes that destroys movies, you know? Because we don’t just want to see imitations of life. We want to see something that is beyond that. Cinema is not just about telling stories. Everybody clings to this. Telling stories, telling stories, telling stories! It’s about light. It’s about space. It’s about tone. It’s about color. It’s about people having experiences in front of you, where, if it’s transparent enough, they can experience it with you. You become them. They become you. That’s the communion. That’s the experience.

Wow. You’ve just summarized my entire philosophy of what cinema is. I don’t really care much about plot.

I don’t either! But we’re all different. My wife is always going, “Don’t tell me what happens.” I couldn’t care less. Tell me the whole story! When I watch it, I’m going to forget about where it goes anyway. It’s not about what happens. It’s about how things happen. Because there’s nothing new under the sun.

You’re remarkably consistent in everything that you describe about yourself in relation to art.

That doesn’t necessarily sound good to me. Consistent?

You have a philosophy that informs why you do what you do.

Good. But you understand that sounds half good and half bad, because once you have a philosophy, then you’ve got a method and then you’ve got to be careful of all kinds of levels of corruption. That’s always the tension. You’ve got to find the sweet spot between control and abandon. And when you’re in the groove — and I’m not always in the groove, nobody’s in the groove all the time — but when you are, you have a real sense of that. And that is a beautiful feeling.

What is the most useful thing you’ve learned in the decades you’ve been doing this?

There’s only going toward things. Don’t do this to get that. Do it for the pleasure of doing it.

More Conversations

- David Lynch on His Memoir Room to Dream and Clues to His Films

- Emily Watson: ‘I’m Blessed With a Readable Face’

- Quincy Jones on the Secret Michael Jackson and the Problem With Modern Pop