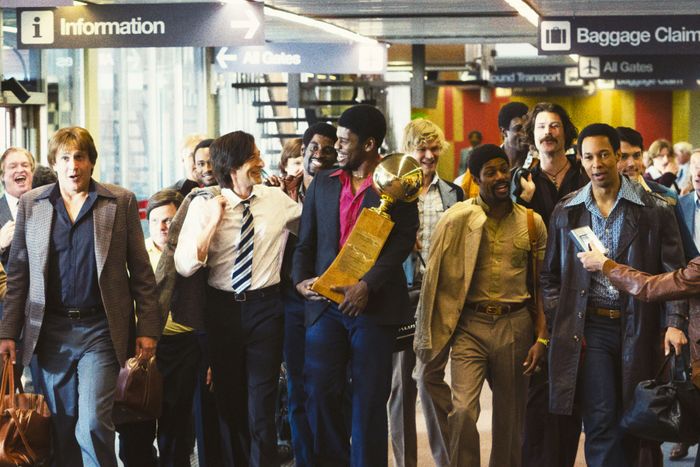

You probably already knew how Winning Time’s rookie season was going to end — and even if you didn’t, a simple Google search would confirm that Jerry Buss and the Lakers won the 1979–1980 season, kicking off the franchise’s storied Showtime era and setting the foundation for Magic Johnson’s long and legendary career. Knowing this preordained outcome deflates the closing stretch of Winning Time’s debut season, which mostly conforms to the typical beats of the underdog sports flick. Despite every setback, whether it’s Spencer Haywood falling back off the wagon or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar sustaining an ankle injury, you always knew the Lakers were going to triumph. (Listen, it’s literally called Winning Time.) And so by the time you reach the final episode, the show practically feels like it’s on autopilot.

Such is the challenge of the sports biopic or, for that matter, any of the ballooning number of fictionalized TV shows based on true-life events. How do you spin a narrative that keeps people engaged when the broad shape of the story is already known? Most of the time, shows answer this question simply by filling in the blanks: Here’s what you don’t remember, here’s what you didn’t know, isn’t that crazy? More recently, the answer has increasingly come to take the form of psychological and moral interpretation, as evident in this year’s spate of TV shows about high-profile start-up scandals: The Dropout, WeCrashed, Super Pumped. Winning Time falls more into that latter category, but its specific challenge feels trickier. Firstly, what more can be said about the Showtime Lakers, whose legacy loudly persists to this day? (One of the more annoying things about NBA media is how the Lakers always seem to be a major story line even when they are absolute trash.) Secondly, how does the show get someone who isn’t already invested in Showtime Lakers mythology to care about the struggles of a team they know is going to win … and win and win and win? Is there anything more boring than a dynasty?

Winning Time makes the case for its existence by focusing on the subjective experience of the era. Time has a way of smoothing out the edges, as do the narratives set by the victors, who get ample opportunity to frame, refine, and soften their place in the story over the decades. One of the more compelling things about Winning Time is its commitment to going the distance on those hard edges. It seems motivated by processing the individual people of the Showtime Lakers through the emotional context of the sweaty and capitalistically chaotic ’80s. Executive producer Adam McKay has a clear fixation on this moment, which features an America and a basketball league on the verge of radical transformation under the Reagan presidency. Last year, McKay produced a podcast called Death at the Wing (presumably using research compiled for Winning Time) that surveyed various high-profile deaths in the NBA through the ’80s and early ’90s, which he argues were emblematic downstream effects of Reaganite policy and its corrosive racial politics, facilitation of immense wealth explosion, and debilitating approach to drug policing. In Winning Time, this interest is most acutely telegraphed through the production’s somewhat divisive mood and visual style: It’s hyperactive, it’s twitchy, it’s excessive, and it feels very true to the messiness of the era.

For the most part, Winning Time’s takes on the people within and around the Showtime Lakers orbit really worked for me, though it’s worth noting that, as a viewer, I wasn’t particularly interested in devout historical fidelity. (I’m a huge basketball fan, but I’m not that kind of fan.) When it comes to a production like this with an obvious sense of perspective and voice, I’m more interested in the show’s interpretation of who these people were in the moment, how they related to each other and the world, and what they would come to mean to the culture at large. Winning Time has very specific ideas on all these things, and the maximalist presentation of these character studies is aided in no small part by excellent performances from some seriously fun actors. Quincy Isaiah is a revelation as the young Magic Johnson, a spark plug whose confidence and megawatt smile become gradually tempered, but never diminished, as he navigates the league and the limits of his self-belief. I was also particularly taken by the show’s conception of Jack McKinney, the ideological architect of the fast and fluid Showtime play style who never made it to the end of that breakout 1979-1980 season. Tracy Letts, always great, plays him as an obsessive, ornery, tragic genius, a characterization distilled in a whimsical moment that portrays McKinney floating in air as he’s lost in thought sifting through offensive plays. It’s a childish, cartoonish image. It’s also really delightful, and not to mention moving, given what ultimately happens to him.

These subjective character ideas are what make Winning Time worthwhile, none more so than John C. Reilly’s central performance as Jerry Buss. All chest hair and cologne, the show perceives Buss as a vibrant man-child emblematic of the era’s dynamics: an extreme beneficiary of American society’s unequal structure whose macho hyperoptimism is fueled by a history of never really failing downward. Winning Time’s Jerry Buss is the pure embodiment of the white, privileged good-time guy, albeit one with a heart of gold, and Reilly is perfect in the role.

It’s been fascinating to watch the responses of Winning Time’s real-life counterparts to the show, which have ranged from dismissive displeasure, in the case of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, to outright scorn, as in the case of Jerry West, who threatened to “take this all the way to the Supreme Court” if he had to over Jason Clarke’s Yosemite Sam–adjacent portrayal of the guy. (For their part, HBO stands behind the show.) There’s much to chew on when considering these responses in the context of professional athletes and how their stories have historically been shaped and preserved. On the one hand, there’s been a hard-fought decades-long shift in narrative control away from the sports media and toward the athletes themselves, which has generally been a good thing, especially when it comes to the dynamic between athletes of color and sports media, historically white. On the other hand, there’s something about this response to Winning Time that feels contiguous to the phenomenon of powerful, famous people being imperially controlling of their image in a way that runs somewhat contrary to freedom of art and expression. Sure, all the living Showtime Lakers have their own recollections of what they lived through, but just because it’s a personal truth doesn’t mean it’s necessarily honest.

Reilly put it best when responding to the criticism in a recent interview with my colleague Lane Brown: “I respect everyone’s right to their own story, but I don’t think that precludes others from telling public stories. And this is a public story. People have said, ‘How can you tell the story of the Lakers without the Lakers themselves?’ And my answer to that is, ‘How could you tell it with them?’” (As a quick aside, this further underlines the sheer miracle that was The Last Dance, a masterful balancing act between powerful stakeholders, narratives, and petty drama.)

The Lakers will always have opportunities to reinforce their version of events. They Call Me Magic, a biographical docuseries featuring Johnson himself, recently dropped on Apple TV+. There’s apparently a Hulu docuseries about the Showtime era currently being produced by Jeanie Buss and Antoine Fuqua, which will feature full participation from the Lakers organization. Buss is also developing a “Lakers-inspired” Netflix workplace comedy with Mindy Kaling. And of course, separate from these television projects, there’s everything else: Magic’s tweets, Kareem’s Substack, the struggling Lakers, the League. Winning Time mostly works because it’s willing to push back on the notion of a shared “official” history, break from the usual hymns of nostalgic sports lore, and dig into the messy subjectivity that gets smoothed over in the construction of a legacy.

Which is why the season finale ultimately felt so inert. As we barrel through the finals and zero in on the Lakers’ eventual triumph, the show becomes increasingly conventional, doubling back way too hard toward the underdog-sports-flick component of its DNA. The interesting work the show had been doing with its characters is pushed to the side in order to give this fictional iteration of the Showtime Lakers the glory that syncs them up with the image held by their real-world counterparts. Winning forgives everything, as they say, but watching a preordained win is unforgiving in its insipidity. This may well prove to be a fundamental storytelling problem for the show as it continues: Because the Showtime Lakers won so much, as a fictionalized story “based on true events,” it seems like Winning Time can only lose.