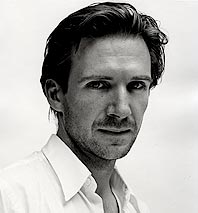

On the face of it, there’s plenty for Ralph Fiennes to be grateful for these days: The revival of Brian Friel’s Rashomon-like Faith Healer, in which he plays the title role, sold out in Ireland before it opened, drew rave reviews, and is hitting Broadway (previews begin next week) with $4 million in the bank.

But something has Fiennes on edge—and it isn’t just the cold he’s caught with three performances left in Dublin. At a moment of high acclaim, he sounds like he’s under siege. “Sometimes you can just feel an audience sitting back and waiting to be entertained,” he says. “They’re just looking forward to the restaurant afterwards.” The play, about a shaman whose power intermittently eludes him, requires intense concentration, and one night, during Fiennes’s final monologue, when a cell phone went off in the front row, he broke character and shouted, “Turn that fucking thing off!”

Fiennes waves it away. “One incident,” he says, “and the whole Irish press has gone mad. About one silly little thing.”

Of course, one other silly thing had invaded the sanctity of the theater. “There was one very distinctive boo” on the press night, says co-star Ian McDiarmid, “and Ralph knew that it had absolutely nothing to do with his performance.” Rather, it “was to do with the perceived notion of Ralph’s private behavior, which had been mercilessly exposed all over the tabloids.”

That would be the February revelation of a two-year affair between Fiennes and a Romanian singer—which led to the breakup of Fiennes’s ten-year relationship with Francesca Annis, an actress nineteen years his senior whom he’d met when she played his mother the last time he was on Broadway, in Hamlet. He’d left his wife, actress Alex Kingston, for Annis, which for the U.K. press was a split on par with the Bennifer breakup. (HARRY POTTER STAR IS A LOVE RAT, harrumphed the Sunday Mirror about the latest scandal.)

Fiennes, who won’t discuss his private life with the press, will say only that New York may not prove a respite. (He once threatened to sue the Post over insinuations about him and Gina Gershon.)

But in a way, this current role is tailor-made for an actor reckoning with the consequences of his public fame and private flaws. Frank, the Irish healer, travels with his girlfriend and manager through Wales and Scotland in search of rubes hoping for miracles. When he returns to Ireland, though, his notoriety portends disaster. “The play is about the burden of talent,” says its director, Jonathan Kent, who also directed Fiennes in Hamlet. “It wreaks a sort of collateral damage on the person that possesses it and on those who come into contact with him. I think Ralph’s talent, and therefore his fame, brings all sorts of horrible things in its wake.”

Fiennes had pictured an Irishman in the role, but he did spend time in Ireland as a kid and he knows from itinerancy. One of seven children raised by a novelist mother and a father who gave up farming for photography, he moved about a dozen times. After attending the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company, perhaps anticipating the storied British Acting Career: Hamlet, Prince Hal, Merchant Ivory epics, maybe a knighthood once your hair’s hoary enough for Lear. (At 43, he still has time for that.)

Yet his fame crossed the Atlantic, thanks to the role of a fat, wasted Nazi in 1993’s Schindler’s List. And before long, it was easy enough to typecast him, based on his affinity for tormented leads in mainstream-arty epics (The English Patient, The End of the Affair, and most recently, The Constant Gardener). His draw is a peculiar mix of open sex appeal and inner turmoil.

That tension is what all those advance buyers are lining up for on Broadway. “He has a great dark charisma onstage which is also capable of sudden, unexpected shafts of light,” says McDiarmid. “But I could equally say he has a light charisma, and now and then it’s occluded by shadows.”

Fiennes sees Frank as “a man held hostage by his own gift. He has a defensive layer of charm. But emotionally, he’s very ruthless.”

Sometimes Fiennes has stretched his own gift to brilliant effect (in Spider and as the monstrous Voldemort in Harry Potter); other times he’s looked ridiculous. Maybe it’s his “aristocracy of spirit,” as Kent puts it, that makes him so wonderful as Hamlet and so terrible as a politician wooing J.Lo in Maid in Manhattan.

He’s prickly about this, too: “People might say, ‘Oh, he’s good at playing these conflicted people, but comedy isn’t his genre,’ ” he says. “But a lot of parts I’ve played, there’s some lightness and humor in them.” His most interesting career move may have been his decision to do Hamlet in a grungy London suburb in 1994, just as his fame was bubbling up here. “In some ways, that should have been career suicide,” Kent says. Instead, it moved to Broadway and won him a Tony, right after his first Oscar nod, for Schindler’s List, came to naught (as would his second, for The English Patient).

His movie work seems to have helped Fiennes move beyond the declamatory style attributed to the Oliviers and Gielguds of the past. “There’s an attention to detail maybe that there wasn’t before,” says Kent.

But there remains something old-fashioned about Fiennes, and it isn’t his Queen’s English. It’s an aloofness, a repression—and the sudden, unexpected release of passion—that probably comes naturally to him even when he isn’t on the clock. The very qualities that make him a great actor have turned him into an awkward, defensive celebrity.

As you’d expect, that’s just the kind of analysis that Fiennes finds anathema. “Actors use who they are to be someone else, but I would hate to ever think I’m playing myself,” he says. “It’s imagining being someone else that is the key motivating thing for me. So when people want to know about me, it makes me a bit unnerved.”

The characters in Faith Healer are all hiding something, but the way they tell their stories is what nearly gives them away. The same could be said for Fiennes. Even the least prying of questions—does he prefer theater to film?—unsettles him. He says he finds moviemaking almost more frustrating than it’s worth. Why, then, make so many of them?

“When it works, it’s fantastic. But what I’m saying,” he adds, his speech accelerating, his voice rising, “is that it’s not that I don’t like films. It’s the process, and you have to get into your head a positive attitude towards microphones and camera equipment and endless waiting and constant breaking of the rhythm … But you asked me a question and I’m answering it! The process of theater is very pure, that’s all.” He stops, and lets out an exasperated sigh. He’s tried to explain himself. Now can he please go explain someone else?

BACKSTORY

It’s hard to take 31-year-old Cornelia Crisan’s version of her affair with Fiennes at face value, but the 2,600-word piece on their relationship in the Daily Mail leaves little to the imagination. She says he pursued her relentlessly, claiming the “mothering” Annis wasn’t satisfying him. Among their 30 trysts, she says, were some she found eerily reminiscent of his sex scenes with Julianne Moore in The End of the Affair. She decided to bare her soul to a tabloid, she says, because it was the only way she could end their affair—which left her frustrated, since “he was a cheat.”