Every summer, Wellington Chen, the director of Chinatown’s Business Improvement District, dispatches interns to document all the businesses that have recently opened and closed in his neighborhood. He has noticed an overwhelming number of empty storefronts being filled by independent pharmacies. At the same time, senior and adult day-care centers have been proliferating — starting with a 19,000-square-foot building the city has installed on Centre Street. Chen says it’s a subtle indication of a trend: As so many immigrants’ children have left for college and never returned, and as other families have sought real estate in the outer boroughs (particularly in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, and Flushing, Queens), most of the people left in Chinatown’s historic core are the elderly dwellers of rent-regulated apartments.

How can this possibly be the state of one of the most desirable tracts of real estate in all of Manhattan? After all, Chinatown is hedged in by three of the borough’s priciest neighborhoods: Soho to the north, the Financial District to the south, and, to the west, Tribeca, where the monthly cost of a one-bedroom averages $5,100. Developers would eagerly replace Chinatown’s tenement buildings with market-rate housing for young professionals or gut the existing buildings, leaving only the tea parlors and dumpling shacks. A similar fate has already befallen the Chinatowns of Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., which have been reduced to ethnic theme parks where longtime residents have been priced out and new immigrants no longer come. And Manhattan’s Chinatown is built on the graveyards of enclaves past: the Irish Five Points, the Jewish Lower East Side, and Little Italy.

But Chen is right: So far, Manhattan’s Chinatown has largely resisted the laws of the real-estate market. Often defined by the rough borders of Delancey and Chambers on the north and south, and East Broadway and Broadway to the east and west, the neighborhood is still populated primarily by low-income Chinese, its storefronts are still dominated by Chinese mom-and-pop operations, and it remains a cultural and commercial hub even for expats in the outer boroughs. It has found ways to keep its internal economy humming even after its garment factories folded in the 1990s and early aughts. While the neighborhood is not immune to pressures — some restaurants are shuttering because of rent escalations, new hotels and luxury apartments are appearing on the periphery, and wealthier tenants are slowly filling vacancies in some of the old buildings — it is, broadly speaking, an exceptionally tight-knit and self-sustaining city unto itself.

Here are portraits of what could be called the Chinatown Establishment: a collection of people with deep roots in the neighborhood and unusual influence in shaping its future. Some wield familiar levers of power, like political position and real-estate portfolios. Others are included for reasons more particular to the neighborhood: pastors to the devout, third-generation herbalists, restaurateurs, labor activists (who have more muscle in Chinatown than just about anywhere else). Their visions for the neighborhood’s future, and their worries for it, vary considerably. (Such is New York.) But overall, they stand a fighting chance of controlling the fate of some of the most valuable land in the city. Here are five reasons why.

1. They own the place.

Eric Ng is known to practically every longtime resident as “the mayor of Chinatown.” An entrepreneur who emigrated from Hong Kong in 1970, he was reelected last year as the leader of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), which represents the interests of some five dozen cultural organizations and “family associations,” grouped by immigrants’ last names. For decades, the CCBA effectively functioned as Chinatown’s government, collecting dues and overseeing business transactions. “If there was an argument, they didn’t come to court,” Ng says in his office at 62 Mott Street. “They came to us.” The most powerful community figures worked through the CCBA. As Chen says, “There are people behind the scenes who choose the Eric Ngs of this world.” Those figures once functioned like a village council, providing “stability and order.” They’re still around, and most are businessmen, many retired, some now living in the outer boroughs. But they no longer carry the authority they once did.

Still, the family associations’ most enduring achievement is a momentous one. During the 1960s and ’70s, they bought up about 60 buildings in Chinatown’s historic core, mostly on Mott, Pell, and Bayard Streets, that they still own collectively. They rent out the bottom floors to stores and restaurants, and the rest they use as apartments, many for the elderly. They also retain community space, which they use for huge galas during the Lunar New Year. “They’re sitting on a gold mine,” says Margaret Chin, the councilmember representing lower Manhattan, who grew up in Chinatown. A similar mixed-use building on East Broadway, previously owned by a realty company, sold last year for $20 million. But because dozens of people have shares in the family associations’ buildings, they’re almost impossible to sell.

Dwarfing the family associations in scale are the government-subsidized housing developments clustered around Chinatown’s far-eastern edge. The Smith and Vladeck public-housing projects, between the Brooklyn and Williamsburg bridges, are just beyond Chinatown’s traditional borders, but they now collectively house some 2,700 low-income Asian residents. And there are hundreds more in the Confucius Plaza skyscraper on Bowery and in the Two Bridges projects on Cherry Street.

All of this has helped create the conditions for a haven for poor immigrants, but the active efforts of liberal nonprofits are also critical to keeping it that way. The civil-rights group Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), currently run by Christopher Kui, is one of the most powerful forces in Chinatown’s housing market. Since 1995, it has pulled down more than $100 million in grants, donations, and loans to buy tenement buildings and restore them — ensuring that developers won’t raze them instead — and to build affordable housing. It also joins other advocacy groups, such as the Chinese Staff & Workers Association and CAAAV (formerly called Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence), in protecting residents of rent-regulated buildings, filing lawsuits on their behalf when landlords try to evict them illegally. “We’re talking about fighting building by building — it’s a little bit like Groundhog Day,” says Paul Leonard, who works in Chin’s office. “One tenant will give word that they’re getting harassed by their landlord, and it will turn into an attempt to clear the entire building.” In their totality, these little struggles keep Chinatown’s affordable-housing stock from eroding.

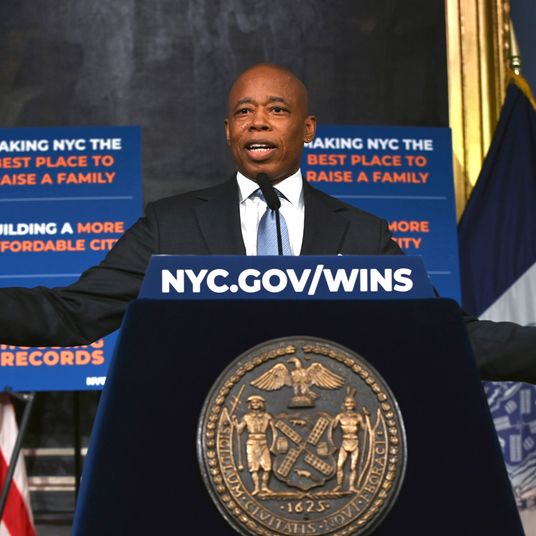

Chin, who is the district’s first Chinese-American councilmember, helped found AAFE and worked there for 11 years. When I ask her why these advocacy groups hold so much sway in Chinatown, she chalks it up to simple logistics. “The area is not that big,” she says. “It’s all right there. You’re able to speak the language and organize.”

2. No one ever truly leaves.

Ethnic bonds are also responsible for the neighborhood’s economic resiliency in the wake of the garment industry’s collapse. During the 1970s and ’80s, clothing manufacturers provided tens of thousands of jobs to uneducated workers, and employees on the late shifts kept the surrounding restaurants and markets buzzing until long past midnight. By the early aughts, between competition from overseas labor and the restricted access to Chinatown in the wake of 9/11, nearly all the factories had closed. At this point, Flushing was attracting middle-class families looking to buy houses, and Sunset Park was appealing to tenants who couldn’t find space in Manhattan. It appeared possible that the original Chinatown would no longer be an essential part of their daily life.

But over the past decade, as other Chinese businesses keep people returning for day trips, Chinatown’s contemporary role has come into focus. Neighborhood banks like Abacus and Eastbank still cater to Chinese immigrants looking to buy homes and start businesses. Sandy Lee, whose family owns the Lee Insurance Company on Pell Street, says her office helps newcomers understand how insurance works and why it’s necessary in the litigious American culture, whereas they never needed it in Hong Kong or Taiwan. “It’s sort of like social work,” she says. The Lau-Kee family built its law firm on immigration cases in the 1960s, and now it concentrates on business and real-estate law for Chinese clients. Sunset Park and Flushing have their own Chinese food markets and restaurants, but Chin says the high concentration of accountants, real-estate agents, and doctors — not to mention the old churches and Buddhist temples — keep Chinatown an essential regional capital for Chinese immigrants.

3. And more keep coming.

Since the early 1990s, a distinct and parallel Chinese community has blossomed in the neighborhood. Unlike the primarily middle-class Cantonese-speaking immigrants who moved to Chinatown in the 1960s and ’70s from Hong Kong, the newcomers are arriving from the farms and fishing villages in Fujian province in southeastern China, where Mandarin is dominant. Two dozen employment agencies on East Broadway have networked with Chinese restaurants across the eastern half of the U.S., so a young Fujianese immigrant with no working papers, knowledge of English, or cooking experience can walk in and immediately land a kitchen job in some distant locale.

To transport them, there are now numerous Fujianese bus companies that make regular trips to cities like St. Paul, Minnesota, and Norfolk, Virginia. With a capacity of more than a thousand people a day, they have expanded their clientele outside the neighborhood, transforming Chinatown into a transportation hub. In addition, there are now at least nine Chinatown print shops that supply menus for Fujianese-owned restaurants in other states; a Chinatown electronics store that supplies the restaurants with software and hardware; and a host of support services on East Broadway that cater to these transient Fujianese workers: moneylenders, gambling facilities, wedding parlors, notaries, and immigration-law offices.

“Chinatown has reinvented itself,” says Peter Kwong, a professor at Hunter College and CUNY who is recognized by many as the dean of Chinatown scholars. “That’s why it’s still here.”

4. It feeds everyone.

Chinatown’s restaurant culture established itself more than a century ago, when early generations of Chinese immigrants was working low-wage jobs across the five boroughs. On Sundays and Mondays, they flocked to Chinatown restaurants for a reprieve from the exclusion and racism they felt in the diaspora, according to the historian Jack Tchen, a co-founder of the Museum of Chinese in America. Even before tourists discovered it, the food defined the neighborhood.

These days, the restaurant owners remain a bellwether of Chinatown’s modernization. Young entrepreneurs are updating some of the oldest restaurants for their own generation. Wilson Tang, 36, runs the Nom Wah Tea Parlor, the neighborhood’s oldest dim-sum restaurant. It opened in 1920 and was purchased by Tang’s uncle in 1974. Tang says he did the unthinkable by serving dim sum for dinner, rather than cutting it off at 2 p.m. like every other Chinatown restaurant, a move several of his peers have now repeated. Without altering the traditional menu, he brought in a wine expert to help him with pairings. He’s also arranged parties with Vogue and promotional events with Nike. It’s a balance of tradition and innovation also being attempted by Christina Seid, whose father started the Original Chinatown Ice Cream Factory in 1977. She tries to introduce her longtime Chinese customers to new flavors; pumpkin pie and rainbow cookie have been especially successful. After years of turning Americans on to durian and pandan ice cream, “it’s like a reverse introduction,” she says.

Crucial to the success of Chinatown’s restaurant scene is its diversity: There’s a wide spectrum of culinary ambition, as many holes-in-the-wall as there are famous institutions, and varying degrees of self-consciousness and tourist-coddling. (Even among the places that cater to tourists, Tang says, there are sometimes secret menus accessible only to Chinese speakers.) There are now Vietnamese, Malaysian, and Thai restaurants, as well as both Fujianese and Shanghainese, reflecting shifting immigration patterns. And some of its least-authentic establishments have also become institutions. Wo Hop, which opened in 1938, has stayed in business by adapting its menu for non-Asian palates. “The Chinese immigrants from Hong Kong, they won’t eat here,” says Ming Huang, who manages the

restaurant on his family’s behalf. “But the ABC — that means American-born Chinese — they like our style food.”

5. It is engaged in an argument with itself.

Neighborhood leaders from every sector agree that they need to orchestrate some kind of change to keep the neighborhood thriving, but prescriptions vary widely. There are those who want disruption. Some of the developers most active on the neighborhood’s periphery belong to the Chinatown community, including Alexander Chu, the chairman of Eastbank, who has drawn criticism for the boutique hotel he’s building at 50 Bowery. Another developer, Shing Wah Yeung, opened a luxury-condo building on Hester Street in 2006, and earlier this year he announced plans to build a 13-story tower for office condos and retail space at Pike Street and East Broadway.

Others see Chinatown’s best future as a continuation of the past. “It’s the spirit of old New York,” says Tchen. “A port culture of people coming on, coming off ships, and intermingling with people of different backgrounds. The neighborhood still embodies that history of just regular people.” Some believe the best way to retain regular people is to agitate against development. The intractable Wing Lam, head of the Chinese Staff and Workers Association, is pushing the city to pass a rezoning plan that would require about half the units in any new building to be affordable, limit building height, and grant special protections to small businesses. Later this month, he will be demonstrating in front of City Hall. The promotional fliers read, “No More High Rents, No More Displacement, Rezoning NOW!”

As newcomers, the Fujianese typically have less investment in preserving the neighborhood’s old character, so many of them support the building of mixed-rate high-rises in order to increase the overall supply of housing. “The No. 1 change we need is zoning,” says Jimmy Cheng, president of the United Fujianese American Association. “Let the people grow up” — he lifted his hand to suggest a vertiginous height — “and make their money.” There will be 205 new units of affordable housing in the 68-story luxury-condo building on South Street, currently being built by Extell Development Company. Some consider this accommodation to the private market shortsighted and irresponsible. “That’s like the Trojan horse of gentrification,” says Kwong. To others, it looks like a win.

This kind of debate over growth is taking place all over New York. What makes Chinatown’s future distinct from, say, Bushwick’s — or Little Italy’s — is the degree to which gentrification can be controlled by the same ethnic group that currently runs the neighborhood. Chinatown’s future may not resemble the Chinatown we know today, but it will likely be hashed out among the Chinese-American residents currently living, eating, shopping, and praying there. “Chinatown will always be here,” Chin says. “But it’s just a question of what kind of Chinatown we want.”

*This article appears in the September 21, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.