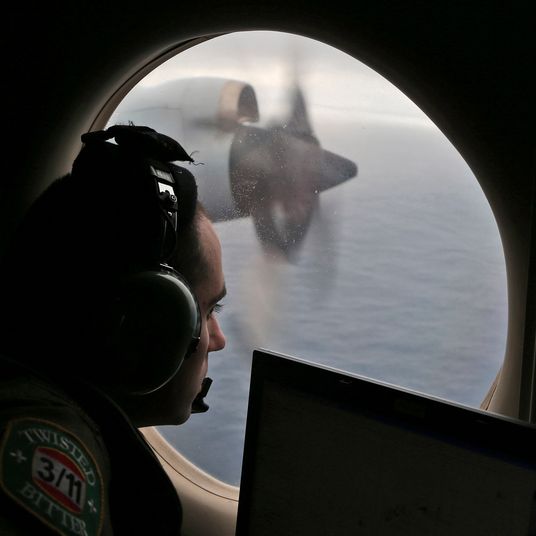

As the costs of grounding the fleet of Boeing 737 Max jets mount — earlier this week, Southwest Airlines said the grounding was partially to blame for $150 million in lost revenue in the first quarter — so, too, do doubts about when the plane will manage to get back into the air. After Boeing announced a slate of fixes it intended to make to the 737 Max, CNBC reported that aviation analysts predict it “will take a minimum of six weeks and up to 12 weeks before the grounded jets are airborne again.”

And even when the Max does get FAA approval to fly again, its troubles won’t be over. Bloomberg reported that China had suspended the plane’s airworthiness certificate, meaning the plane would face additional hurdles before it was able to return to that huge and fastest-growing aircraft market.

Perhaps the question should not be when the 737 Max will return to the sky but whether it should.

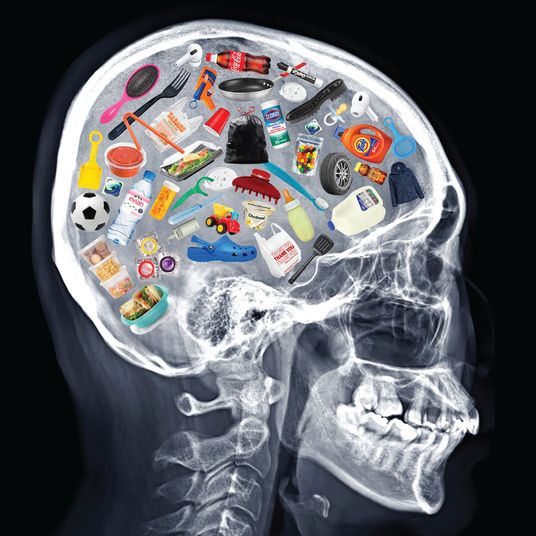

The model’s current problems are the result of a string of decisions dating back more than a half-century; its design shortcomings run far deeper than just a poorly written piece of software.

The story starts the 1960s, when Boeing was setting the specifications for the 737, the plane that would go on to become its best seller to date. Back then, jet travel was in its infancy, and many airports lacked the infrastructure that we take for granted today, such as jetways. “The airplane was designed to sit close to the ground,” says airplane designer and aviation journalist Peter Garrison. “It would have an airstair built into the door so it wouldn’t need exterior arrangements to get passengers off the plane.”

That decision yielded a plane that met the needs of 1960s aviation, but fast-forward to the early 2010s and the world was a radically different place. Airstairs were no longer much of a concern. But decades of jet-engine development had led engineers to conclude that the key to turbofan efficiency was a large diameter.

“Back in the day when the thing was designed, it had little slender engines under the wings, and then as they started putting in these bigger and bigger turbofans, they had to deal with the fact that there wasn’t room under the wing,” says Garrison. Eventually, he says, “they had to move the whole engine forward and upward in order to keep it off the ground.”

This had an undesirable side effect. A more powerful engine, slung far forward, tends to make an aircraft dynamically unstable, especially when the engine is at full throttle and the nose is up, such as during takeoff. “It’s destabilizing in the sense that the more nose-up it is, the bigger the forces tending to make it more nose-up,” says Garrison.

Designers of commercial aircraft generally aim for stability. Imagine carrying a marble in a deep bowl. If you lurch this way or that, the marble will roll, but it will always return to the center. Instability is like balancing a pool cue on your finger: The further it gets away from straight up and down, the more it wants to fall. In the case of an airplane, the higher the nose gets, the higher it wants to go. If left unchecked, this could result in a situation called aerodynamic stall, where the wings lose lift and the plane starts to plummet.

Because the FAA deemed the 737 Max too unstable to be used as a passenger aircraft, Boeing came up with an automated system that would keep the nose from getting too high — the now-infamous “maneuvering-characteristics-augmentation system,” or MCAS. “It was required for certification,” says aviation blogger Peter Lemme.

The 737 Max’s instability problems eerily echoed another ’60s design, the Cheyenne. At the time, Piper Aircraft wanted to build a more powerful version of its popular twin-engine light aircraft, the Navajo. Piper swapped out its piston engines for turboprops. Like the 737 Max, the Cheyenne had a design that involved putting more powerful engines further forward on the wing.

Jack Webb was Piper’s chief engineering test pilot during most of the Cheyenne development process. “As we were going along, I discovered a kind of scary dynamic-stability problem,” he says. It was the same problem the 737 Max would later have, for the same reason. And as Boeing would later do, Piper tried to fix the problem by adding automation — in its case, a device called a “stability-augmentation system” (SAS) that would push the nose down if it got too high.

Webb came to realize that if the pilot wasn’t properly trained, the SAS could actually worsen the instability. The problem was that the system could get into a feedback loop with the human pilot. Not understanding why the nose was starting to go down, the pilot would pull up, to which the SAS would respond by pushing down. Since each has a lag in their response time, they wind up chasing one another, causing the plane to enter a series of increasingly steep climbs and dives.

Recent press accounts have focused on the fact that the ill-fated Ethiopian Airlines and Lion Air planes were equipped with the MCAS, which could be misled if a single sensor returned faulty readings. This would cause it to kick and lower the nose even when the plane wasn’t nose-high. The pilot’s effort to fight the runaway system would cause the plane to porpoise.

Webb believes that this kind of up-and-down motion can take place even when the system is functioning as designed. He has looked at several accidents involving the Cheyenne, “and it’s a classic picture. It looks like the airplane’s on a roller-coaster ride before it crashes. The pilots just get behind the input necessary to stabilize the airplane. They’re fighting it.”

On Wednesday, Boeing revealed the list of fixes it planned for the 737 Max. One was that the MCAS will henceforth take input from two sensors instead of just one. If the sensors disagree, the system will disable itself.

Webb believes that, based on his experience with the Cheyenne, these fixes won’t eliminate the plane’s predilection for roller-coastering. Even if Webb is wrong, and the 737 Max is safe so long as its MCAS is working as intended, that still leaves another problem. A single malfunctioning sensor will cause the system to turn off, thus putting the plane back in the condition that the FAA deemed too unstable to grant an airworthiness certificate.

There is a straightforward solution for all the 737 Max’s problems: to reduce the plane’s pitch up tendency, Boeing could lengthen the landing gear and move the engines further back under the wing; and to increase stability, it could increase the size of the tail. There’s a reason that Boeing doesn’t want to do that. “It would be considered a new aircraft,” explains Garrison.

The whole point of the 737 Max is that, for all its changes and improvements, from the FAA’s perspective, it’s still technically a 737. From a design, testing, and certification perspective, it’s cheaper to update an old design than field a brand-new one. It cost Boeing an estimated $2 billion to $3 billion to bring the 737 Max to market, compared with approximately $10 billion to $12 billion to create a brand-new plane. And legacy airplanes are more attractive to airlines because they don’t have to retrain their pilots.

There’s only so far you can keep updating a venerable design, though. Boeing knows this. In the mid-aughts, it launched a project to consider a clean-sheet replacement for the 737 that would be ready to fly sometime between 2012 and 2015. In the end, though, it scrapped that approach. When Airbus rolled out an update to its own version of the narrow-body aircraft, the A320neo, in 2010, Boeing was forced to respond. Its answer was the Rube Goldberg contraption it has today.

Maybe Boeing’s luck will change and the world will come around to the view that while it may not be perfect, the 737 Max is good enough. Maybe Boeing will go on to fill all the 5,000 orders currently on the books, and who knows, maybe add a few thousand more on top. What will be the result of this rosy scenario? The skies filled with the better part of a trillion dollars’ worth of could-be-better airplanes, when the company could have taken some small fraction of that time and money and just built an aircraft worthy of the Boeing name.