America is getting older. The elderly are living longer. Private pensions are disappearing, working-class wage growth has long been middling, the cost of health care is soaring (and that of breakthrough treatments for ailments common among seniors, skyrocketing), our nation’s birth rate is plummeting — and the problem that these trends collectively create is genuinely vexing.

At present, the median household led by an American between the ages of 55 and 64 has about $12,000 in its retirement accounts. Only a small fraction of the next wave of retirees will collect public or private pensions; these days, most small businesses don’t even offer 401(k)s. Meanwhile, an American who survives until 60 can expect to live for another 23 years (five years longer than in 1970), and the median cost of a private room in an American nursing home is now more than $92,000 a year.

As a result of all this, 18 million baby-boomers are poised to live out their golden years on the brink of bankruptcy. And that is assuming that entitlement benefits are maintained at their current levels. According to government projections, Social Security will take in less revenue next year than it will pay out for the first time since 1982. Absent changes to the program’s funding structure, the Social Security trust fund is expected to run out in 15 years, at which point retirees would see an across-the-board benefit cut of roughly 20 percent.

There is a real crisis here, and it demands a policy response. Unfortunately, the Beltway’s purveyors of bipartisan common sense insist on misdescribing that crisis, and prescribing a cure that would make our actual problem worse.

The New York Times ran a story on Social Security’s looming shortfall this week. Here’s some of the expert testimony that report included:

John Cogan, a professor of public policy at Stanford, said Social Security’s fundamental problem was that benefits had been rising faster than revenue. Cuts, he said, will be unpalatable but inevitable.

“The solution, I think, is to slow the growth in real benefits promised to future recipients,” he said.

… “Entitlement programs in the United States have expanded more than tenfold since their inception, but workers are nowhere near 10 times better off as a result,” the Heritage Foundation said in a May 20 policy proposal. The conservative think tank favors cuts to benefits and siphoning money from payroll taxes into individual investment accounts …

There are no signs of an imminent breakthrough, though Professor Cogan said that, as in the past, the impending prospect of benefit cuts “is likely to change the political atmosphere and make it possible to find a compromise.”

But [former Social Security trustee Robert D.] Reischauer fears that, given the current acrimony of American politics, there will be no compromise until the last minute.

“We will need a combination of increased taxes and reduced benefits, undoubtedly,” he said. “But if we wait, the deficits will only grow and the eventual solution will be much more painful.”

These paragraphs suggest that brave, responsible lawmakers — who were willing to look our looming retirement crisis square in the face — would conclude that cutting retirement benefits was a prerequisite for solving the problem. In reality, such a policy would constitute a cowardly evasion of responsibility. The costs of supporting the elderly don’t disappear the moment they’re pushed off of Uncle Sam’s books. If the government cuts aid to seniors — in a context where the elderly’s private savings are low and getting lower — someone is going to have to pick up the slack. As Rachel Cohen recently noted in The New Republic, “More than 40 million people provide unpaid caregiving, spending on average 20 percent of their incomes each year on expenses like mortgage payments and medical bills.” These burdens don’t just fall on individuals, but also on the broader economy. Working-age people who must sacrifice time, investments in education, or job opportunities to provide for their elders will be less productive than those who don’t.

A serious response to the retirement crisis requires tackling its underlying causes. America’s prime-age population is not fixed in stone. As President Trump so often laments, there are a lot of working-age foreigners who would love to immigrate to our country, if we’d open our borders to them. Expansionary changes in immigration policy could go a long way toward mitigating the fiscal challenges of properly caring for a massive cohort of retirees. And these changes could be paired with social programs that subsidize child care, and other family expenses, thereby helping the many Americans who say they would like to have more children — if only they could afford it — supply our country with more adorable future workers.

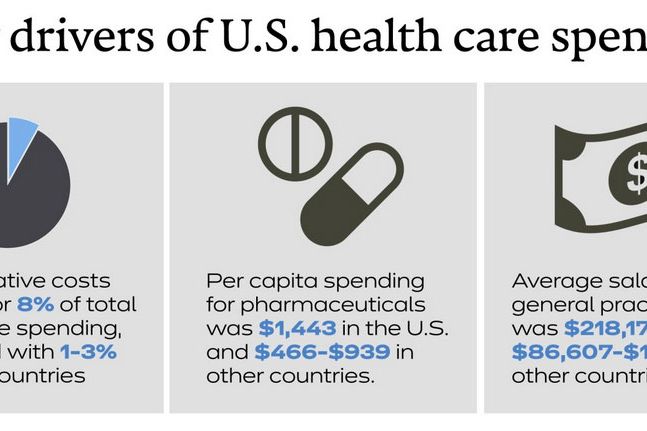

Further, the exceptionally high and rising cost of health care in the U.S. is not a fact of nature. Relative to citizens of other countries, Americans wildly overpay for drugs, administration, physicians, and most hospital procedures. Imposing stiff cost controls on the health-care sector — whether through the establishment of a single-payer system, or some other form of all-payer rate setting — would go a long way toward easing seniors’ financial burdens, and our government’s fiscal ones.

These sorts of direct measures may not fully solve the problem. Some budgetary sacrifices may need to be made. But there is little basis for believing that the American people want those sacrifices to fall to Social Security beneficiaries, rather than high-income taxpayers, or the military-industrial complex. Last year, Gallup found more than two-thirds of Americans saying that the U.S. spends either enough or too much on its military. Meanwhile, in recent polls, upwards of 70 percent of voters oppose reducing Social Security benefits or raising the age of eligibility for the program. Other survey data suggests that voters would rather raise the cap on Social Security taxes (currently, such taxes only apply to the first $132,900 of personal income) than cut benefits.

Now, raising taxes more broadly, aggressively cutting defense spending, and dramatically expanding legal immigration are not hugely popular propositions. But again, neither is reducing benefits to the elderly. And given that older Americans are going to comprise a rising share of the electorate in the coming decades, it seems plausible that many policies that aren’t politically possible today will become so, when and if they are presented as necessary means of avoiding cuts to elder benefits (or perhaps, for funding increases in such benefits).

Meanwhile, as a substantive matter, it would be utterly reasonable for the U.S. to decide to pare back on defense and hike up taxes, as a means of keeping its promises to seniors. America’s tax level, as a percentage of GDP, is much lower than most of its peers in Western Europe, as is its level of social spending. To say that our existing safety net is so generous that it cannot possibly be sustained by tax rates that are compatible with economic growth is to deny the existence of Scandinavia.

We do, however, spend more on our military than China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India, France, the United Kingdom, and Japan spend on their militaries, combined. Which means that we could spend far less than $686 billion a year on the Pentagon and still maintain absolute military supremacy (if you’re into that sort of thing).

In fact, as Democrats on the Senate Budget Committee recently illustrated, if you subtract the past 18 years of tax cuts and increases in defense spending from Uncle Sam’s tab, 2018’s $779 billion deficit becomes a surplus.

In its report on Social Security’s shortfall, the Times repeatedly referred to entitlement reform as “the third rail of American politics,” characterizing it as a necessary measure that craven politicians are too afraid to touch. But the truly taboo ideas in American politics are those that deficit hawks treat as literally unthinkable, even as they sighingly condemn the nonaffluent elderly to work until they die.