For most of the past four decades, Corporate America has preached the gospel of “shareholder value” — a creed that insists the sole obligation of every firm is to maximize returns for its investors. Popularized by libertarian economist Milton Friedman in the 1970s, this theory of corporate ethics provided American businesses with a catchall rationalization for socially destructive practices. Relocating production to exploit disorganized labor overseas, despoiling the natural environment to achieve new efficiencies, and gaming tax laws to maximize profitability — all could be justified in the name of serving the corporation’s only true constituency.

Or at least such measures could be justified in the realm of corporate governance. Whether America, as a society, wished to tolerate such practices was an entirely separate question. Friedman’s argument wasn’t that companies must be allowed to do anything they wish for the sake of increasing returns to shareholders, only that it was up to democratic governments, not CEOs, to draw the boundaries on legitimate enterprise.

A chief executive who decides to prioritize “social responsibility” over profitability is, Friedman writes, “in effect imposing taxes, on the one hand, and deciding how the tax proceeds shall be spent, on the other.” The economist derided this as an anti-democratic usurpation of public authority:

We have established elaborate constitutional, parliamentary, and judicial provisions to control these functions to assure that taxes are imposed so far as possible in accordance with the preferences and desires of the public; after all, “taxation without representation” was one of the battle cries of the American Revolution … Here the businessman — self-selected or appointed directly or indirectly by stockholders — is to be simultaneously legislator, executive, and jurist.

Insisting that social responsibility was a concern for the state, not the C-suite, was a convenient line for captains of industry in the late 1970s. As the combination of rising foreign competition, inflation, and wage demands shrank American firms’ profit margins, many large companies were desperate to break the social contracts (literal and figurative) they’d inked in the postwar boom times. Meanwhile, with the conservative movement in ascendance, telling citizens displeased with the new style of corporate governance to take their complaints to Uncle Sam was a low-risk mode of deflection.

But now, corporate America’s calculus has changed. “Populist” voices in both major parties have grown louder, making calls for frontal assaults on the prerogatives of private capital audible in mainstream discourse. Confiscatory top tax rates, aggressive antitrust enforcement, and various measures to strengthen labor’s bargaining power have regained political relevance and intellectual respectability. Meanwhile, the inequities of contemporary capitalism have grown too conspicuous for elite opinion to ignore or apologize for (when America’s superrich enjoy an average life expectancy 15 years longer than its poor, crowing about how lucky the indigent are to have cellphones and refrigerators doesn’t sell).

In this context, the notion that corporate managers have no right — let alone a responsibility — to steer the economy toward more socially beneficial outcomes does more to undermine CEOs than to liberate them. If there is a broad consensus that the status-quo economic system is socially undesirable and if, as the theory of shareholder value holds, corporations have an obligation to comport themselves as sociopathic, profit-maximizing automatons whose avarice is constrained solely by the letter of the law, then the only answer to calls for change is to pass sweeping new legal limitations on the authority of corporations.

For these reasons, this development is both unsurprising and unencouraging:

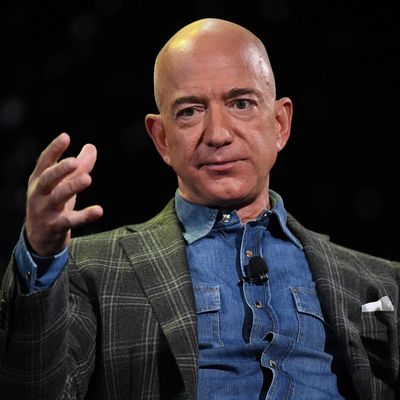

Nearly 200 chief executives, including the leaders of Apple, Pepsi, and Walmart, tried on Monday to redefine the role of business in society — and how companies are perceived by an increasingly skeptical public.

Breaking with decades of long-held corporate orthodoxy, the Business Roundtable issued a statement on “the purpose of a corporation,” arguing that companies should no longer advance only the interests of shareholders. Instead, the group said, they must also invest in their employees, protect the environment, and deal fairly and ethically with their suppliers.

“While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders,” the group, a lobbying organization that represents many of America’s largest companies, said in a statement. “We commit to deliver value to all of them for the future success of our companies, our communities, and our country.”

Coverage of the Business Roundtable’s rejection of shareholder value has been largely positive, while criticism has focused less on the substance of the lobby’s new position than its alleged insincerity in adopting it. And all things being equal, it is probably preferable for corporate executives to acknowledge that Friedman’s theory rests on unsupportable premises and that their firms have ethical obligations to the workers and communities that sustain them.

But the Business Roundtable literally exists to prevent the U.S. government from statutorily mandating corporate America’s fulfillment of such obligations. Founded in 1972, the lobby played a leading role in blocking the creation of a consumer-protection agency — and a progressive revision of labor law — under Jimmy Carter, thereby setting the stage for an era in which the interests of those “stakeholders” were ruthlessly subordinated to those of corporate stockholders (very much including the Business Roundtable’s membership). In light of this history, the lobby’s statement reads less like an argument for a less-profit-driven corporate culture than a case against a more democratically managed economy.

After all, the Roundtable’s statement isn’t any kind of mea culpa. The signatories aren’t pledging to change the business practices that have heretofore enabled many of them to evade federal taxation, despoil the climate, or award themselves upwards of 254 times more in annual compensation than their median employees. Rather, the statement suggests that all Roundtable members have long been practicing the conscious capitalism they prescribe and merely neglected to share the good news with the world:

Since 1978, Business Roundtable has periodically issued Principles of Corporate Governance that include language on the purpose of a corporation. Each version of that document issued since 1997 has stated that corporations exist principally to serve their shareholders. It has become clear that this language on corporate purpose does not accurately describe the ways in which we and our fellow CEOs endeavor every day to create value for all our stakeholders, whose long-term interests are inseparable. [my emphasis]

Meanwhile, the statement asserts in its opening that “the free-market system is the best means of generating good jobs, a strong and sustainable economy, innovation, a healthy environment, and economic opportunity for all.” Precisely what constitutes a “free-market system” is never specified. But given the lobby’s history, it seems safe to assume that it is not a catchall for all non-command economies but merely a propagandistic euphemism for “a market economy structured by laws no more progressive than those already on the books in the United States.”

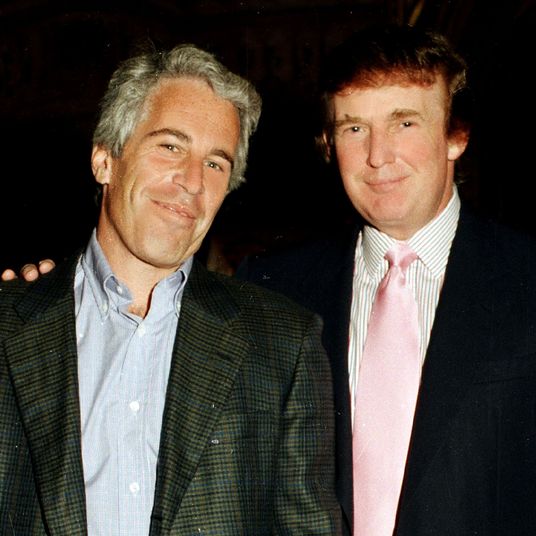

And if this is the case — if the Business Roundtable is not withdrawing its opposition to progressive labor-law reform or new consumer protections or sweeping policies for decarbonizing the economy — then all its progressive-sounding commitments on corporate governance are worth less than an IOU from our businessman-in-chief.

In the Roundtable’s statement, the CEOs promise to compensate their workers “fairly” and to provide “important benefits.” They pledge to deal “fairly and ethically with our suppliers” and “protect the environment by embracing sustainable practices across our businesses.” But since the signatories do not specify what constitutes fair compensation, important benefits, ethical contracting, or sustainable practices, their promises don’t add up to an assumption of responsibility so much as an assertion of authority.

They are not inviting the public to hold them to a democratically determined set of business standards. They are saying they are the ones who get to decide what American capitalism’s “stakeholders” deserve — and the public can trust them to do so fairly because we’re all “conscious capitalists” now.