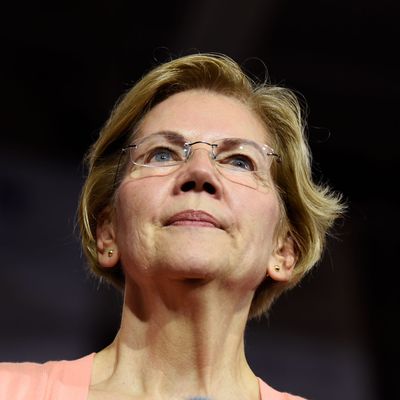

Elizabeth Warren is campaigning on a plan to impose a 6 percent tax on fortunes larger than $1 billion, and then use the resulting revenue to fund some combination of child care, housing, green manufacturing, and universal health insurance.

Meanwhile, the American economy is drowning in capital. The rise of China, globalized financial markets, and historic wealth concentration has yielded a savings glut. There is so much money trying to turn itself into profit-yielding investment that global real interest rates have plunged to their lowest level in recorded history. Savers are so desperate for both safety and yield that Donald Trump’s deficit-spending spree hasn’t cost the federal government its exceptionally low bargaining costs — while the manifestly absurd business models of fourth-rate Silicon Valley start-ups have proved insufficient to keep capital out of their hands.

But what if the world were different? What if Warren’s wealth-tax plan (still) topped out at 3 percent and earmarked the revenue for deficit reduction — while the fundamental obstacle to economic growth in the U.S. was a dearth of savings available for investment?

The Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM), an applied-economic-research organization, recently decided to conduct this eccentric thought experiment. And it found that in the alternate dimension where Elizabeth Warren is a deficit hawk — and capital markets are forever partying like it’s 1979 — her wealth tax would slow economic growth by about 0.2 percent a year.

Unfortunately, Penn Wharton — and the New York Times — is now framing this exercise in speculative economic fiction as an analysis of Elizabeth Warren’s actually existing wealth tax.

One of the model’s false assumptions is understandable: PWBM evidently began its research before Warren doubled her wealth tax to help finance Medicare for All. And the outfit could argue that another of its erroneous assumptions was really an act of charity: Since its model treats public debt as a drag on growth, pretending Warren would use her tax’s revenue for deficit reduction actually makes its score more flattering. Had PWBM acknowledged that Warren intends to use her tax’s proceeds to finance social welfare and public investment, the model would have projected a stiffer cost to GDP. As the Times’ Jim Tankersley explains:

The Penn Wharton Budget Model estimated that wealthy Americans would consume more and save and invest less in order to avoid accumulating wealth that would be subject to the tax. The resulting drop in investment reduces economic growth.

“The wealth tax shrinks the economy because saving is more expensive,” said Richard Prisinzano, Penn Wharton’s director of policy analysis. “The results also suggest that the negative effect of the tax increases as the tax rate increases.”

The model did not assess growth effects from Ms. Warren’s spending plans. Instead, it assumed that the tax revenue would be used to reduce the national debt, a move that encourages growth in the Penn Wharton simulation but not enough to counteract the drag on investment.

Nevertheless, however charitable PWBM’s misrepresentation of Warren’s plan may be, it remains a misrepresentation. It simply is not a score of Warren’s wealth-tax proposal.

The biggest problem with the model’s estimate, though, lies with its baseline assumptions about how the economy works. In a world where a surplus of capital has rendered interest rates and inflation undesirably low, why should we assume a reduction in the savings rate of the Über-wealthy would hurt growth? Separately, PWBM’s decision to ignore how Warren actually intends to spend her tax’s revenue ceases to be charitable if one questions its tendentious assumption that deficit reduction is better for growth than investments in child care or green technology. On a rapidly warming planet — where climactic changes threaten to impose ruinous economic costs by the end of the century — why would investing in green manufacturing necessarily be less conducive to long-term growth than paying down the deficit?

This is not an idle question, as the Times notes:

Another economist who has evaluated Ms. Warren’s plans at her request, Mark Zandi of Moody’s, wrote on Wednesday that his analyses suggested that her spending on “child care, housing and green manufacturing would spur economic growth and produce more tax revenue.”

Not all of PWBM’s dubious economic assumptions work against Warren. For example, the reason Congress offsets spending with taxes (to the extent that it does) is not because money is scarce. The federal government can print dollars in unlimited quantity. What is scarce are the real resources available for consumption at any point in time. Put too many dollars in the hands of too many people eager to spend them, and you’ll set off a bidding war for scarce goods that produces inflation. The point of raising taxes to “pay for” a new child-care benefit is, thus, to guard against the possibility that such spending would boost demand to inflationary levels.

One implication of this is that not all new spending needs to be offset dollar for dollar: If inflation is low, and demand relatively weak, increasing the supply of dollars in circulation can be economically beneficial. But a separate implication is that any given tax only functions as a true “pay for” to the extent that it reduces demand for real resources. And yet it’s not actually clear that a wealth tax would have such an effect, since it wouldn’t reduce the billionaire class’s capacity to consume to any appreciable degree. On the contrary, if one accepts PWBM’s logic, the tax would actually increase consumption by incentivizing the wealthy to spend instead of save. Thus it’s possible that a wealth tax wouldn’t actually “pay for” much of anything in real terms, so much as it would produce more “responsible”-looking budget numbers.

All of which is to say: The Penn Wharton Budget Model has demonstrated that if one stipulates a bunch of tendentious, business-friendly assumptions about how the economy works, then a wealth tax that vaguely resembles Elizabeth Warren’s would slow growth. Which tells us approximately nothing worth knowing. Mainstream media outlets should not suggest otherwise.