In mid-January, at the conclusion of a special meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society, the venerable free-market organization, after appearances by Condoleezza Rice and Niall Ferguson, Peter Thiel was slated to give closing remarks on “Big Tech and the Question of Scale.” The keynote was the latest in a series of public remarks and interviews in which the PayPal founder and Facebook investor showed his prominence in conservative politics.

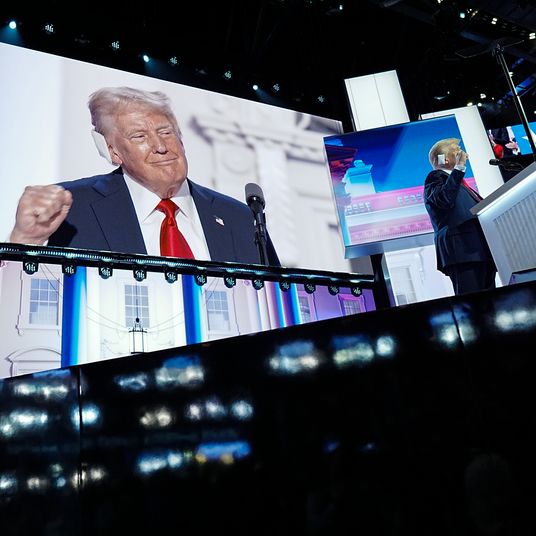

Thiel has long been a political donor; in 2016, he gave $4 million across various campaigns, including $1 million to a super-PAC supporting Trump, on whose behalf Thiel spoke at the Republican National Convention. He’s known to have funded right-wing hoaxer James O’Keefe and has been an enthusiastic sponsor of organizations for activists and intellectuals, like The Stanford Review, a conservative publication he founded in the 1980s. Earlier this month, he announced an investment in a Midwest-focused venture-capital fund led by Hillbilly Elegy author and social conservative J.D. Vance.

But unlike other major right-wing donors, Thiel seems intent on being known for his intellect as much as his wallet. Over the past year, he has played the role of outraged patriot, endorsing Trump’s trade war and bizarrely accusing Google of “seemingly treasonous” behavior in its China dealings. He intermittently lectures at Stanford. Vanity Fair has written about his hot-ticket L.A. dinner parties, where guests (including, at least once, the president) hold “deep discussions” about the issues of the day. Last year, George Mason University professor and economist Tyler Cowen called Thiel “the most influential conservative intellectual with other conservative and libertarian intellectuals.”

This emerging Republican macher is a far cry from the ultralibertarian seditionist who used to encourage entrepreneurs to exit the United States and start their own countries at sea. But Thiel is no stranger to inconsistency. For decades, he cultivated a reputation as a radical Silicon Valley anti-statist; in 2009, he wrote that Facebook, in which he was an early investor, might “create the space for new modes of dissent and new ways to form communities not bounded by historical nation-states.” Yet, six years earlier, he had co-founded the most aggressively “statist” company in the 21st century: Palantir, the global surveillance company used, for example, to monitor Iranian compliance with the nuclear deal. Can you really claim to uphold individual freedom if you’re profiting from a mass-surveillance government contractor? Are you really a libertarian if you’re a prominent supporter of Trump?

It would be easy enough to chalk up the seeming contradiction of Thiel’s thought to opportunism or pettiness (he famously funded a lawsuit, in secret, to bankrupt Gawker, my former employer) or perhaps even a mind less ambidextrous than incoherent. But it’s worth trying to understand his political journey. Thiel’s increasing prominence as both an intellectual in and benefactor of the conservative movement — and his status as a legend in Silicon Valley — makes him at least as important as more public tech CEOs like Mark Zuckerberg. In fact, he still holds sway over Zuckerberg: Recent reports suggest Thiel was the most influential voice in Facebook’s decision to allow politicians to lie in ads on its platform. What Thiel believes now is likely to influence the next generation of conservative and libertarian thinkers — if not what the president believes the next day.

How to square Thiel’s post-national techno-libertarianism with his bloodthirsty authoritarian nationalism? Strangely, he wants both. Today’s Thielism is a libertarianism with an abstract commitment to personal freedom but no particular affection for democracy — or even for “politics” as a process by which people might make collective decisions about the distribution of power and resources. Thiel has wed himself to state power not in an effort to participate in the political process but as an end run around it.

If we wanted to construct a genealogy of late Thielism, one place to start might be a relatively little-read essay Thiel wrote in 2015 for the conservative religious journal First Things. Thiel is a Christian, though clearly a heterodox believer, and in “Against Edenism,” he makes the case that “science and technology are natural allies” to what he sees as the inborn “optimism” of Christianity. Christians are natural utopians, Thiel believes, and because “there will be no returning” to the prelapsarian paradise of Eden, they should support technological progress, although it may mean joining with “atheist optimists,” personified in the essay by Goethe’s Faust. At least Faust was “motivated to try to do something about everything that was wrong with the world,” even if he did, you know, sell his immortal soul to the Devil.

Thiel suggests that growth is essentially a religious obligation — “building the kingdom of heaven today, here on Earth” — and that stagnation is, well, demonic — the chaotic sea “where the demon Leviathan lives.” This binary appears frequently in Thiel’s writing, where “progress” is always aligned with technology and the individual, and “chaos” with politics and the masses. If Thiel has an apocalyptic fear of stasis, you can begin to see why his politics have changed over the past few years, as it has become less clear whether the booming technology industry has actually added much to the economy or to human happiness, let alone demonstrated “progress.”

Where some of his fellow libertarians have moved toward the center, attempting to build a “liberaltarianism” with a relatively strong welfare state and mass democratic appeal, others have found themselves articulating a version of what Tyler Cowen, in a recent blog post, called “state capacity libertarianism,” a concept he says was influenced by Thiel’s thinking. In its essence, it’s the admission that “strong states remain necessary to maintain and extend capitalism and markets.” Where Thiel would differ with state-capacity libertarians like Cowen is that he isn’t merely a believer in strong states in the abstract as agents of economic progress. He is purported to be a specifically American “national conservative,” at least per his conference-keynote schedule. Thiel has suggested in the past that such a conservative nationalism is the only thing that can provide the cohesion necessary to re-create a strong state. “Identity politics,” he suggested in an address at the Manhattan Institute, the free-market think tank, is a distraction that stops us from acting at “the scale that we need to be focusing on for this country.” MAGA politics is the only way to grow.

This is the context in which it makes sense for a gay, cosmopolitan libertarian like Thiel to throw his support behind a red-meat conservative like Senate candidate Kris Kobach of Kansas. The technological progress Thiel associates with his own personal freedom and power is threatened by market failure and political chaos. A strong centralized state can restore order, breed progress, and open up new technologies, markets, and financial instruments from which Thiel might profit. And as long as it allows Thiel to make money and host dinner parties, who cares if its borders are cruelly and ruthlessly enforced? Who cares if its leader is an autocrat? Who cares, for that matter, if it’s democratic? In fact, it might be better if it weren’t: If the left’s commitment to “identity politics” is divisive enough to prevent technological advancement, its threat outstrips the kind of bellicose religious authoritarianism that Kobach represents. A Thielist government would be aggressive toward China, a country Thiel is obsessed with — while also seeming, in its centralized authority and close ties between government and industry, very much like it.

There is, of course, another context in which it makes sense for Thiel to join forces with social conservatives and nationalists: his bank account. Thiel’s ideological shifts have matched his financial self-interest at every turn. His newfound patriotism is probably best understood as an alliance of convenience. The U.S. government is the vessel best suited for reaching his immortal techno-libertarian future (and a lower tax rate), and he is happy to ride it as long as it and he are traveling in the same direction. And if it doesn’t work out, well, he did effectively buy New Zealand citizenship.

*This article appears in the January 20, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!