Just before the holiday weekend, on the day that Donald Trump stood beneath Mount Rushmore and warned against “a merciless campaign to wipe out our history” and the day before his Washington, D.C., fireworks display generated air pollution 15 times the EPA standard and roughly equivalent to the choking megacities of India and China, the state of Arizona reached a terrible pandemic milestone. For the first time in its history, indeed for the first time in any state anywhere at any point in American medical history, the Arizona Department of Health Services activated its crisis standards for hospitals, giving them more flexibility (and less liability) to triage the overwhelming number of new COVID-19 patients and ration care, presumably by focusing on those who could use it most and declining to treat the grimmer cases.

This was once the terrifying nightmare scenario: American hospitals overwhelmed as they had been in Lombardy, Italy, at the outset of the pandemic. In the spring, it was said we had to do everything we possibly could to avoid this situation — to flatten the curve, even if we couldn’t suppress the disease, so at the very least our hospitals were able to treat all those who needed care. The country as a whole has achieved little else in its pandemic response, as painful as the three-month lockdown was, but it did achieve that. Had achieved that, rather. On Tuesday, Arizona recorded 3,653 new cases. Tuesdays are typically bad ones for coronavirus data, collating cases and deaths that don’t get counted over the weekend. But this Tuesday, 117 patients died, four times the state’s previous peak.

It’s not just in Arizona, where, over the last week, there have been more new cases per capita than anywhere else in the world — making it the epicenter of a global pandemic whose primary incubator, for several months now, has been the United States. In Texas, an ICU doctor at San Antonio Methodist told CNN, in what became a heartbreakingly viral interview, that he had received calls for ten patients to be transferred to his unit, but only had space for three.

Over the last month, the San Antonio hospital system as a whole has seen roughly a tenfold increase in patients. In the Rio Grande Valley, ten of 12 hospitals are already full. Officials in Austin and Houston believe in each city that overall hospital capacity could be overwhelmed in ten days. The state is divided into “trauma service regions”; the East Texas Gulf Coast region, east of Houston and home to more than a million, has six ICU beds available and 364 coronavirus patients. And, as everywhere in Texas, the caseload is growing. In Florida, 54 hospitals in 25 counties report they are already at capacity, with no ICU beds available at all; in 30 other hospitals, intensive care units were already 90 percent full or more. (This after refusing to make public hospital data for several weeks.) On Tuesday, the state reported 7,347 new cases — an all-time high. In total, the state now has 213,000 confirmed cases.

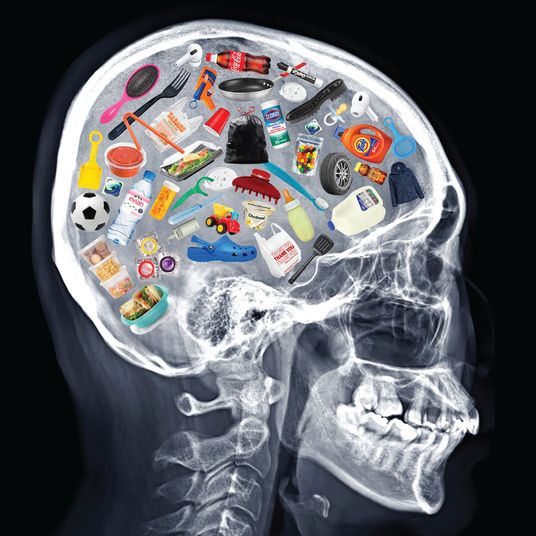

It didn’t have to be this way. Fighting a pandemic is difficult work, even more so when the disease is “novel,” our understanding of it fast-evolving, and the population, at first, entirely unexposed. From a certain vantage, one can even marvel at just how thoroughly and how quickly the activity of the world was reoriented around fighting this disease. Even here in the United States, with a know-nothing narcissist in the White House presiding over a do-nothing governing party that has — over decades but especially during this administration — kneecapped the federal bureaucracy into a state of say-nothing subservience, its tradition of quasi-separatist libertarianism and its culture of entitled grievance and its all-encompassing partisan culture war, even here the country’s states snapped into lockdown, the vast majority of them by just March 30. At that point, there had been about 3,000 deaths and 164,000 confirmed cases. Today, we are north of 3 million cases and 134,000 deaths. At the outset of the pandemic, Americans were horrified by the experience of Wuhan, which tabulated 50,000 cases officially, in total. The U.S. is now adding 50,000 cases every single day. The death toll has risen 45-fold since the country went into lockdown.

You may think that toll is, while tragic, what it means to be living through a pandemic — deaths multiply. But among all the world’s wealthy countries they have only multiplied like this in America. In part, that is because, along with everything else the pandemic has highlighted about this country — its racial inequities, its yawning class divides, its toxic partisanship, its hobbled state capacity — it is maddeningly ineducable. None of these new outbreaks, defining America’s summer experience of the disease, had really gotten going before New York, the worst-hit place in the country this spring, had gotten a handle on its terrible outbreak. And yet none of them managed to learn from New York’s example.

The result is that, in the ominous words of the CDC’s Anne Schuchat, “we have way too much virus” in the country right now to entertain hopes of truly containing it. Way too much virus.

The rest of the country could have learned some lessons from New York, as New York could have learned its own lessons from earlier outbreaks elsewhere in the world — from the horrors of Lombardy but also the models of Taiwan and Japan, among others, not to mention the mixed but illuminating experience of Wuhan itself. But while many parts of the country did rush into lockdown — given how fraught pandemic politics are now, with the caseload worsening, that fact seems more improbable by the day — almost none took the the opportunity, and time, offered by those lockdowns to actually build out any kind of institutional prophylaxis against the disease: scaling up a mass-testing regime, hiring into contact-tracing programs, descending on nursing homes with public-health personnel and PPE, and enforcing around those most vulnerable communities something like a legitimate, protective quarantine. Hardly any leaders even floated mask-wearing advisories until they were themselves neck-deep in a local pandemic crisis. They could not learn from others, only taking actions like these in a sort of last-gasp panic state.

Distressingly, this has not just been an American problem, though the United States has distinguished itself by not just refusing to learn from the example of other nations but from itself. With the exception, perhaps, of New Zealand, practically speaking, across the entire west, nobody has managed to properly and preemptively prepare for this pandemic. No nation across Europe was able to proactively learn from others who suffered first and take protective action accordingly — nobody instituted social distancing in time, advised mask-wearing early enough, or built out testing fast enough to avoid at least a period of terrifying rapid pandemic growth. Everyone had to suffer themselves, and learn for themselves, through that suffering and death. In Europe, this meant that every nation failed first before ultimately succeeding. In America, it has meant failing once in the spring and now again in the summer, with the prospects increasingly grim for a robust response in the fall, when the pandemic will likely intensify, thanks to the moderate effect of seasonality on coronavirus transmission. In some places, like New York and California, we are not just failing to learn from other states, but failing to learn all that well from our own experience, earlier in the spring. The first failure is one of hubris: Western nations looking on a disease outbreak in Asia and feeling protected by a sense of cultural superiority and wealth, and disregarding the emergency response in China and other nations as a reflection not of the seriousness of the disease but of an imagined, innate conformist authoritarianism. The second is a bit harder to name, but it does seem peculiarly American — a pattern of failure following failure, with each successive failure normalized by the last, which should have shaken us out of complacency.

If failing to prepare at first is dangerous cultural arrogance, what is it to just give up? Already, there have been a fleet of damning postmortems assessing and picking apart the total failure of the country to respond in the winter. But that failure wasn’t final, or ultimately determinative, since many other countries that failed similarly at first have managed to quite dramatically turn things around. But not the United States, which is failing again every single day. As James Surowiecki joked morbidly, “We’ve tried nothing, and we’re all out of ideas.”

Worse still, there are few signs this trajectory might change anytime soon. The most encouraging news, terrifyingly enough, comes from the disease itself: As the caseload explodes, fatality rates continue to fall, as Trinh Nguyen among others has pointed out, and indeed America’s per capita death rate is bundled closely with most of the other nations of western Europe. But experts caution against drawing too much optimism from that fact, since we don’t entirely understand what explains the drop (younger people getting the disease, at least for now; vulnerable people protecting themselves better, at least for now; marginally but meaningfully improved treatment in hospitals; a variety of epidemiological factors, including a mutation that may increase infectiousness but not severity or the protective benefits of “cross immunity” inherited from other coronaviruses) or how long it will last (the daily death toll, which has been declining steadily for months, is almost certain to begin climbing again; given the caseload, the question is how tragically fast that ascent will be).

That is what counts as the good news — the current course of a pandemic disease that has already killed 134,000 Americans. On the side of public response, it is, outside of the northeast, almost all bad news. Where we have built contact-tracing programs, they are failing. There are again looming shortages of PPE. Republicans are less worried about the coronavirus than they were in April, and are not wearing masks at any higher of a rate even though conventional public-health wisdom has hardened around that guidance. Texas senator John Cornyn recently took to Twitter to ask, rhetorically, whether anyone could explain why Houston and Dallas had such similar fatality numbers, despite having very different caseloads, only to be told that the state’s doctors and nurses had set up a call with him to discuss these very questions, which he then bailed on. As Andy Slavitt, Barack Obama’s head of Medicare and Medicaid, has pointed out, the country could have produced enough high-quality N95 masks for every single American to have one by now, but hasn’t. Reopenings are supposed to happen when states get down to one case per million residents; Florida is at 400 cases per million, and growing, and hasn’t yet returned to lockdown. In Spain, the country put a region of 200,000 back into lockdown after just 60 new cases.

In theory, the U.S. could be testing much more widely, indeed even testing every American every single day or every three days as Harvard plans to, generating enough medical surveillance capacity to actually suppress the disease, as so many other countries have, even though the majority of transmission seems to be from pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic patients; instead, the lion’s share of testing is devoted to those with symptoms, meaning the country is, almost by design, missing the majority of the problem. (And the CDC is advising schools and universities against widespread testing, as unfathomable as that may seem.) Symptomatic test capacity has expanded somewhat dramatically, as Donald Trump is so fond of pointing out, but lab capacity has lagged far behind, meaning that, in many parts of the country, patients have to wait five days, sometimes more, before getting results, a delay that renders those results, if not entirely useless, than largely so. In Arizona, the results are taking weeks.

Trump’s former FDA head Scott Gottlieb, among others, has applauded the arrival of a rapid-response test capable of delivering results within 15 minutes — but FDA approval is not the same thing as nationwide, easy-access availability, and even the optimistic projection from the manufacturer is to produce merely 2 million tests a week by the end of September. But while there are hopes for fast-arriving vaccines, as well, this week a German biotech company, hyping its own vaccine by promising it would be ready by December with several hundred million doses produced by then, nevertheless acknowledged that it could take fully ten years, even with such vaccines, for the world to reach sufficient immunity the disease would truly disappear. And as Slavitt wrote in an illuminating and troubling Twitter thread on July 6, while early returns from vaccine studies have been promising, vaccines currently in development promise considerably less than hopeful Americans might think: protection more like the annual flu vaccine, which shields only about 40 percent of the population, rather than an iconic silver-bullet vaccine like the one for measles, mumps, and rubella, which protects 97 percent. Slavitt shared some optimism about possible therapies, as well, particularly monoclonal antibody treatment, adding that “so far science is doing as well as our leaders are doing poorly.” But without leadership and a willing, educable public, science can only get us so far — to a “new normal,” in Slavitt’s words, rather than anywhere close to true disease eradication. This is a post-vaccine, post-therapy-innovation new normal, keep in mind, and one that may also feature much more mask-wearing, as well. “What’s in this new normal?” Slavitt says he asked the scientists and researchers he was surveying. “Will I be able to hug my grandmother?” “The answers landed on ‘I hope so,’” he reported. “But no promises.”