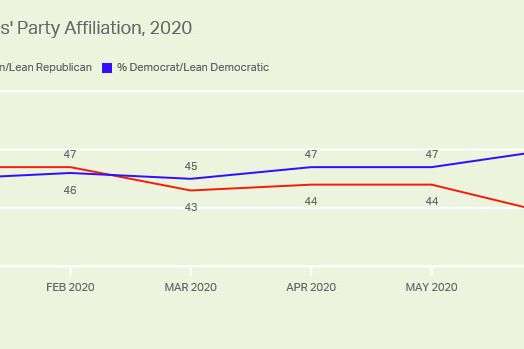

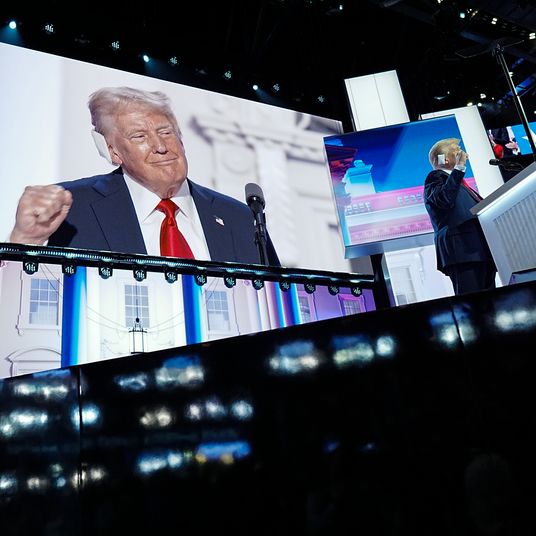

At this moment in time, the most significant fact about how the GOP coalition is changing is that it is getting smaller. Back in February, slightly more Americans identified as Republicans than as Democrats in Gallup’s polling; today, the Donkey Party leads in partisan identification by a margin of 50 to 39 percent.

Given the extraordinary context in which this survey was taken, one could plausibly argue that the result is an illusory byproduct of nonresponse bias, or the marker of a durable, pro-Democratic realignment. To the extent that partisans exhibit a greater tendency to answer calls from pollsters when they are eager to discuss politics — because their side is doing well — then this would seem like a bad time to get Republicans to come to the phone.

Conversely, to the extent that presiding over a catastrophic failure of governance can impair a party’s brand in a long-lasting fashion — as ostensibly happened with Herbert Hoover’s GOP and (more arguably) Jimmy Carter’s Democrats — then having your party’s standard-bearer counsel the public to inject disinfectant while a pandemic kills 140,000 Americans and plunges the nation into the worst recession since World War II seems like it could do the trick.

Regardless, another significant way that the GOP coalition is changing is that its voting base is becoming more working-class. And if this November does bring a “blue tsunami,” that fact could theoretically have some bearing on how the Republican Party rebrands and rebuilds in the aftermath.

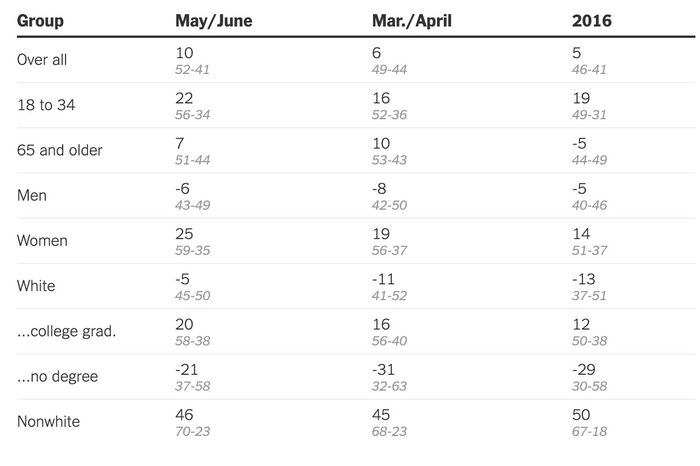

Donald Trump’s erosion of support in recent months has been driven by the defections of white voters in general, and college-educated ones in particular. A variety of recent polls have found Biden leading Trump among the latter by roughly 30 percentage points. Although the president’s standing among non-college-educated whites has declined significantly in recent weeks, he still boasts a roughly 20-point lead with that demographic in the most recent surveys.

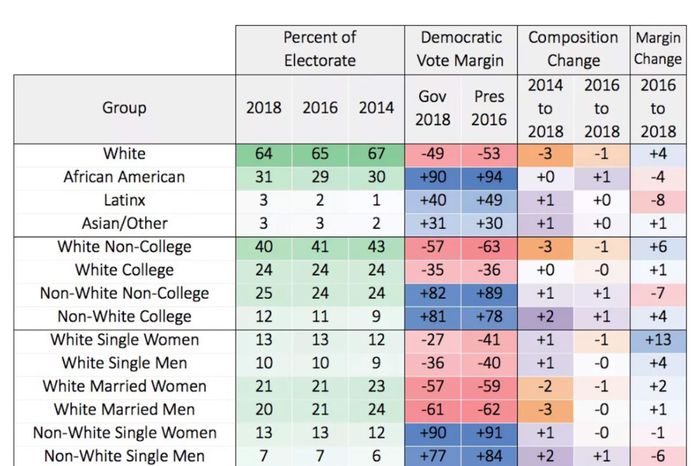

Counterintuitively, the president’s grip on a sizable minority of nonwhite voters has scarcely loosened: In recent polls from CNN, Monmouth University, and the New York Times, Trump’s share of the African-American and Hispanic voting blocs remains about where it was in 2018 exit polls — which was itself a bit higher than his share in 2016.

Considering that the pandemic and recession have harmed nonwhite Americans disproportionately — and that Trump has turned his appeals to white racial grievance up to 11 since the onset of the George Floyd protests — this is a rather surprising phenomenon. And it is possible that a collapse in Trump’s nonwhite support is still in the offing. But, at least before the pandemic, the president’s modest gains among Black voters wouldn’t have surprised some close observers of African-American political behavior. Keeping 90-plus percent of African-Americans united in one partisan camp takes work. The reason Democrats have enjoyed such a landslide margin among Black voters — despite considerable ideological and attitudinal diversity within that demographic — is not that each individual African-American Democrat concluded that the GOP was hostile to people like them through their own personal ruminations on current affairs. Rather, as political scientists Ismail K. White and Chryl N. Laird argue in their book, Steadfast Democrats: How Social Forces Shape Black Political Behavior, the Black bloc vote is a product of “racialized social constraint” — which is to say, the process by which African-American communities internally police norms of political behavior through social rewards and penalties. In their account, the exceptional efficacy of such norm enforcement within the Black community reflects the extraordinary degree of Black social cohesion that slavery and segregation fostered.

If this thesis is correct (and White and Laird do much to substantiate it), then it would follow that the erosion of African-Americans’ social isolation would weaken racialized social constraint, and thus, narrow the Democratic Party’s margin with Black voters. And, according to the Democratic Party data scientist David Shor, the polling bears out this thesis: Young, secular Black voters — whose distance from the African-American church makes them less subject to social constraint — have become slightly more Republican since 2016.

The Democrats’ triumph in the 2018 midterms was powered by college-educated whites, even in races where one might have expected a groundswell of nonwhite support to put the party over the top. In Georgia’s gubernatorial election, Stacey Abrams’s share of the state’s Black vote was 4 percentage points lower than Hillary Clinton’s was in 2016, according to the Democratic data firm Catalist.

The source of the relative stability of Trump’s Latino support is less well-theorized. But it is true that, holding ethnicity constant, non-college-educated voters tend to be more conservative on immigration both in the U.S. and in other countries. It is conceivable that some of the same qualities that make Trump’s politics appealing to white non-college-educated voters also serve to ingratiate him with a minority of working-class Latinos, particularly those generations removed from the immigrant experience.

Regardless, since the Latino and African-American voting blocs are more working-class than the electorate as a whole, one effect of the GOP holding its ground among nonwhite voters — while bleeding white college-educated ones — is to render its coalition less affluent and highly educated than it was in 2016.

This is the scintilla of truth behind Ted Cruz’s remarks on the Federalist Radio Hour Thursday.

“The big lie in politics is that Republicans are the party of the rich and Democrats are the party of the poor. That just ain’t true,” the Texas senator told the right-wing outlet. “Today’s Democratic Party is the party of Silicon Valley billionaires. Today’s Democratic Party is the party of Michael Bloomberg. It is the party of power, it is the party of suppression, it is jackbooted thugs who will enforce their will through force.”

Setting aside Cruz’s last remark (by all indications, the president wants the GOP to be known as the party of jackbooted thuggery), he is narrowly correct that the Democratic Party boasts more support from affluent voters than at any time in its modern history (although American billionaires still donate predominately to the GOP, and controlling for educational attainment, Republicans still soundly beat Democrats among high-income voters).

And yet: If the GOP is becoming more working-class, in terms of its coalition’s demographic composition, there are few signs that it is becoming a party “for the working class,” in the sense of governing in the interests of workers as workers. By the same token, while the Democratic Party is becoming more affluent demographically, its economic policies have grown steadily more progressive over the past decade. Since taking control of the House of Representatives on the strength of the party’s support in suburban districts, Nancy Pelosi’s caucus has passed a $15 minimum wage, The Protecting the Right to Organize Act (a pro-union labor-law reform bill), and pushed to have the CARES Act provide Americans with the highest unemployment benefits on offer anywhere in the world (albeit, on a disastrously temporary basis).

By contrast, since Donald Trump eked out an Electoral College majority by making significant inroads with lower-income white voters, he has established himself as (at least arguably) the most economically regressive Republican president in history. He began his presidency with an attempt to throw 14 million low-income Americans off Medicaid, and then proceeded to shower wealthy capitalists in tax cuts, make it easier for corporations to cut costs by poisoning children, and gutted the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, among other reactionary things.

Now, with tens of millions of Americans freshly unemployed, upwards of 20 million at risk of eviction by autumn — and state governments poised to layoff public-sector workers and slash social services due to cratering revenues — the Republican Party is putting its principled commitment to slashing welfare provision above its political interests. There is no evidence that the CARES Act’s $600 weekly federal unemployment benefit is starving the U.S. labor market of much-needed workers by making joblessness more rewarding than hard work. On the other hand, there is copious evidence that such benefits have stabilized personal income levels in the U.S., thereby preventing a much sharper recession.

Nevertheless, the party of “single moms” and “steelworkers” finds the theoretical threat of American workers having the power to turn down an unattractive job offer from an employer — without suffering a significant loss of living standards — so offensive, it is fighting to slash the incomes of 32 million Americans (in the middle of a pandemic, just months from Election Day).

Meanwhile, the party’s other top priority for the next COVID-19 recovery package is to immunize employers from workplace safety lawsuits.

It is true that the Republican firmament is home to some conservative intellectuals who would like the party to embrace a more communitarian economic vision. Many religious conservatives have lost their reverence for plutocracy as neoliberal capitalism and cultural traditionalism have come to appear increasingly incompatible. Some dissident wonks, like former Mitt Romney policy advisor Oren Cass, have gone so far as to embrace sectoral bargaining, a policy that would enable an industry’s workers to set minimum compensation standards that would apply to all employers in that sector.

But no major Republican lawmaker has crossed that Rubicon. Instead, as the Roosevelt Institute’s Mike Konczal notes, the GOP’s putative populists, like Missouri senator Josh Hawley, have opposed pro-union reforms and minimum-wage hikes while pretending that immigration is the primary driver of working-class wage stagnation in the U.S. As Konczal writes:

If, like me, you’ve told people on the populist right ‘there’s no evidence in the debates that immigration is among the top five reasons of wage stagnation; to whatever extent it exists the declining minimum wage is far more important by itself’ and just watched the blinking eyes, you know there’s a gap here. I think the coverage of the “debate” over immigration and wages does a disservice here, because the range of the numbers in no way matches the scale of the fall in fortunes for American workers. The debate is between “increased wages” and “minimal decline, and just for the small group of non-native-born Americans without a high school diploma.” Even if you believe the high estimates, they pale in comparison to the things even moderate Democrats want to accomplish, and you should be skeptical of those estimates.

Contra [conservative commentator Saagar] Enjeti, full employment and a tight labor market aren’t determined by the number of people in the country — immigrants take jobs, but they also create jobs through spending — but instead by fiscal and monetary policy, demand and technology. There’s a pretty standard toolkit among the left for compressing the income distribution and raising wages— unionization, higher minimum wages, public programs, overtime, wage boards, high progressive taxation on the rich, sectoral bargaining, high aggregate demand and full employment, etc. — to draw from. Historically and across nations, these are the things that work. It’s telling that members of the populist right do not endorse these and even actively fight them (populist right Senator Josh Hawley supported right-to-work laws in Missouri), and also do not provide serious alternatives to them.

Given the hegemony that business conservatives have enjoyed over the American right’s core institutions of policy and leadership development, the safe money would be against the Republican Party embracing a remotely prolabor economic agenda in the coming years, even if there were a significant faction within the GOP advocating for such a turn. As is, there is only a cohort of opportunists who’ve wedded marginally heterodox views on a few discrete issues to vituperative denunciations of a rootless, godless professional-managerial class.

So, the GOP is (almost certainly) not becoming a party for the working class. Whether it will become the preferred party of 51 percent of working-class voters is less clear. Given the relative sturdiness of the GOP’s share of non-college-educated voters throughout three years of reactionary policy-making — and five months of catastrophic misrule — it seems possible that well-packaged pseudo-populism may be all the party needs to grow its blue-collar wing. All true friends of American labor must do what they can to guard against that possibility.