All around the country, memorials to the racist Lost Cause of the Confederacy are coming down or, in the case of military facilities named after Confederate leaders, being redesignated. Many monuments, typically erected during the Jim Crow era to symbolize resistance to racial equality, occupy key public locations in southern cities.

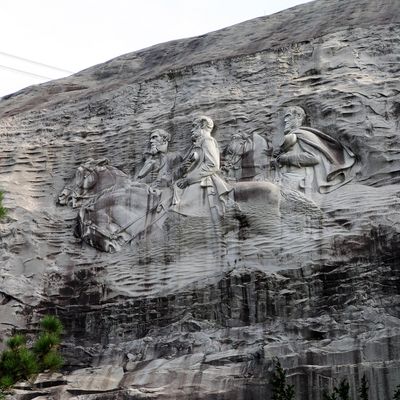

But there’s nothing quite like Georgia’s Stone Mountain, a giant outcropping of granite in the suburbs of Atlanta that bears a three-acre carving of Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson on horseback. The question of what to do with this very deliberately constructed tribute to those who tried to overthrow the U.S. government in defense of slavery is unavoidable. And it’s a very public issue: The carving and the surrounding park is owned by the State of Georgia, thanks to a purchase engineered by a segregationist governor in the 1950s whose entire career was built on racist provocations. Indeed, as a history of the carving and the mountain itself published by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution attests, the whole saga provides a great introduction to the pathologies of neo-Confederacy, and a refutation of those who pretend monuments to the Lost Cause are merely historical.

During many of the years when the Confederate sculpture was under construction, it was on private land owned by a family intimately involved in the Ku Klux Klan, which held regular cross-burning meetings atop the mountain. (One participant in these rituals is now acknowledged as initiating the 20th-century revival of the murderous white-supremacist movement.) Indeed, there was one proposal to surround the Confederate leaders on the sculpture with hooded Klan riders to make clear the connection between the armed rebellion of the 1850s and latter-day racists.

The Jim Crow era had drawn to a close by the time the carving was dedicated in 1970, but conservative pols still worshiped at the shrine of the “men in gray,” Tyler Estep recalls:

About 10,000 people — a fraction of the 100,000 forecast by organizers — attended the ceremony.

Vice President Spiro Agnew spoke in lieu of President Richard Nixon, who was distracted by recent developments in the War in Vietnam. In his 12-minute speech, Agnew held up the men carved on the mountainside as pillars of American virtue.

Later, Georgia’s secretary of state took the stage, donned a gray cap and let out a Rebel yell.

The crowd joined in his yell, which the Atlanta Constitution called a “long lusty cheer.”

That would have been Secretary of State Ben Fortson, first elected in 1946.

All this history is coming to a head next week when the board of the state authority that manages Stone Mountain Park will meet to consider proposals to deal with the giant embarrassment.

The board is not expected to endorse the simple idea embraced by many civil-rights activists, including 2018 Democratic gubernatorial nominee Stacey Abrams: to sandblast the carving right off the mountainside. Governor Brian Kemp, who narrowly defeated Abrams in 2018 and will likely face a rematch with her next year, has opposed such measures. In a tweet two years ago, Kemp said, “I will protect Stone Mountain and historical monuments in Georgia from the radical left. We should learn from the past - not attempt to re-write it.” But even Kemp now seems defensive about the monstrosity, appointing a Black minister as chairman of the park’s board.

More than likely, the board will propose “contextualizing” the carving with exhibits on the whole history of its planning, development, and dedication, while also getting rid of some of the park’s antebellum trappings that make the whole place feel like the set of Gone With the Wind. In other words, an effort will be made to “learn from the past,” which kind of misses the point the carving loudly tries to make that the past really isn’t past at all.

As it happens, I spent a good chunk of my life near Stone Mountain, or passing it on the way to Athens, and always regarded the carving as an ugly monument not to the Confederacy but to the determination of white conservative Georgians to ensure its hateful legacy lived on and on. Perhaps the state should take a page from the demolition of the Berlin Wall and give Georgians the opportunity to wield a sledgehammer or a laser and do some damage to the carving as a sort of spiritual reparation. Anything would be better than pretending this mammoth exhibit represented an innocent effort to honor the dead.