Dick Harpootlian slipped out of the South Carolina General Assembly on April 20 to tell me why people on death row should be allowed to die by firing squad. “My experience in this area probably exceeds most people’s,” he said, noting the death penalty cases he had handled during his time as a prosecutor, on and off, between 1975 and 1995. His most famous was that of Donald “Pee Wee” Gaskins, who had already been convicted of murdering nine people when Harpootlian charged him with a tenth murder in 1983. Gaskins got sent to the electric chair in 1991. Harpootlian chose not to watch him die — “There are plenty of prosecutors who relish the idea of executing somebody,” he told me. “I’m not one of them” — but the stories still haunt him. “His blood boiled, his hair almost caught on fire, his eyes … I think they did explode in his head,” Harpootlian recalled. “And it wasn’t that quick. They had to give him two jolts.”

It is probably no wonder that Richard B. Moore, a death-row inmate in South Carolina, chose an alternative. Until the South Carolina Supreme Court issued a temporary stay on the execution that had been scheduled for April 29, three agents with the state Department of Corrections had been planning to strap Moore to a chair, place a hood over his head, and shoot him through the heart. That Moore, who more than two decades ago killed a store clerk while fighting for control of the clerk’s gun during a robbery, opted to die this way is both an indictment of his options and a testament to Harpootlian. Bringing back death by rifle fire for the state’s first execution since 2011 was a shocking idea when the 73-year-old lawyer and current Democratic state senator first argued for it in March 2021. He described it at the time as a “desperation move to minimize the pain and suffering of the condemned.”

The state senator “abhors” the death penalty except for “extreme cases,” he said to me, and he still sees Gaskins as a “poster child” for why capital punishment has its place. “The only time we can relax our vigilance on Pee Wee is when he is in Hell,” Harpootlian quipped less than a week before the execution. But, he elaborated to me, “if it should be done in some instances, I felt that being shot was a much quicker, much less cruel way to do it.”

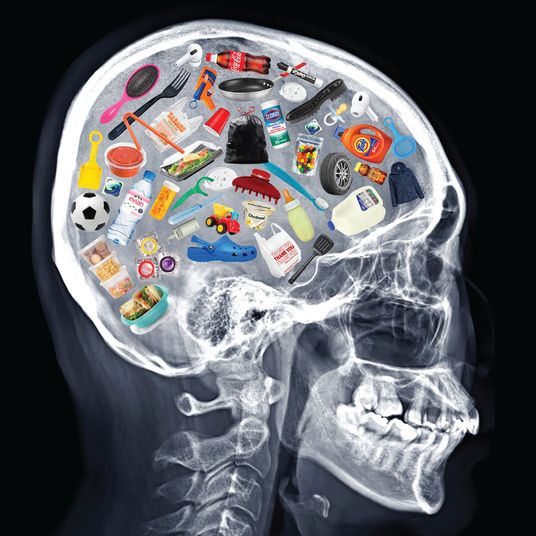

South Carolina has joined the swelling ranks of states that have had trouble obtaining the drugs needed to kill people by lethal injection. Pharmaceutical cocktails used to be seen as the humane option when compared to methods like hanging and the gas chamber, but a mix of advocate-driven pressure and botched killings have made drug companies skittish. (In 2014, an Oklahoma man named Clayton Lockett started to convulse and speak after being declared unconscious on the execution table.) Some companies have placed tough restrictions on procuring the necessary drugs, while others have pulled them from the market altogether. Last spring, when South Carolina’s depleted stockpiles prompted legislators to propose a new law that would have made the electric chair the default option for people on death row, Harpootlian insisted, along with a Republican colleague, that they be given the choice to die by firing squad, too.

“There’s no good way to kill somebody,” he explained to me, but at least the firing squad was usually “instantaneous.” It is an option in Utah, a fact Harpootlian cited as evidence of its preferability, even as Moore, the condemned man, maintains that South Carolina “is forcing me to choose between two unconstitutional methods of execution.”

To support the death penalty in any form is to rationalize a taste for cruelty. It is notoriously error prone, applied with racial bias, and does not deter bad behavior. It has less public approval today on a national level than at any point since 1972, and if the testimony of shaken witnesses is any indication, the slim majority that still supports it might reconsider if more supporters were to actually witness what it entailed. South Carolina’s decision has caused such an outcry and attracted national news coverage partly because it has banished the medicalized abstraction that made some executions more palatable. It forced people to conjure mental images of a perfunctory killing method most associated with death squads and enhanced them with real ones: On April 15, the Department of Corrections shared a photo of its newly renovated and soon-to-be gore-slicked $53,600 death chamber in Columbia, replete with two austere chairs (one for being electrocuted; the other for being shot).

There are ways in which South Carolina’s situation is emblematic of the souring promise of 2020, when there appeared to be broadening agreement in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder that this country’s criminal-justice system was too punitive. Support grew across the U.S. for a range of reforms, and police favorability fell to dramatic lows. Congress was poised to take positive, if modest, bipartisan action. But it did not take long for people to change their minds. Supportive institutions shuttered or collapsed as a response to the COVID pandemic, and their absence began to show: People who were sick, jobless, aimless, and angry had fewer places to go for help. Whenever these people hurt themselves or others, it showed up for their neighbors as terror and for governments as spikes on their crime-tracking spreadsheets — both bad for politics.

And once the problem had been reframed as a criminal one, the solutions became blunter and more craven. Once-sympathetic Republicans left the negotiating table and resumed being cynical antagonists. Democrats rushed rightward out of fear. The Trump administration, which had announced it would restart federal executions in 2019 for the first time in 17 years, embarked on a furious killing surge at the end of the president’s term.

What we are seeing seems to be a course correction — less a fearsome backlash to a revolutionary moment than the smoothing of waters after a ripple. “No, no, no, no,” Harpootlian replied when I asked if he could envision the death penalty’s popularity dipping enough in South Carolina to kick-start its demise. The impulses being grappled with there, as Moore and others on death row await their fate, are among humanity’s darkest. “They don’t want it to be quick,” Harpootlian said of some of his colleagues in the legislature and their views on electrocution. “They don’t want it to be painless.”

Whether a hail of bullets should be a consoling alternative to a 2,000-volt blast of electricity or a heart-stopping pharmaceutical cocktail is already evident. “There are a number of people out there that are volunteering to be the marksman on this,” Harpootlian told me before hurrying back to the General Assembly. “The fact that they want to see somebody die or they want to participate legally in killing somebody, it should raise great concerns with our society.”