Since November 11, 2022, the day that Sam Bankman-Fried’s crypto exchange FTX collapsed and his hedge fund Alameda Research collapsed and his personal $26 billion turned out to have been vaporous, the twitchy 31-year-old, maybe-genius, maybe-scammer failed to raise $8 billion to save the company, gave a lot of weird interviews denying he did anything intentionally wrong, tried to blame his ex, was charged with eight counts of fraud and conspiracy, spent a week in a Bahamian jail, had enough of that, got extradited to the U.S., pleaded not guilty in New York, moved in with his parents in California on a $250 million bond, got accused of witness tampering, talked with Michael Lewis, got yelled at by a judge for violating bail terms to watch the Super Bowl, witnessed his former executives flip on him, started a Substack, got hit with four more charges, gave interviews to the rest of the journalists he hadn’t already gotten around to, successfully got a charge on illegal campaign contributions dropped on a technicality, got charged with another count of bribing Chinese officials, had a few charges separated to a different criminal suit, leaked his ex’s diary, got incarcerated again on the grounds that he “attempted to tamper with two witnesses,” complained about not getting his food or medicine while in jail (fair), complained about not having enough computer time in jail (ehhhhh), and got personally sued about three dozen times in the federal courts.

At last, his trial starts on Tuesday, October 3, 2023. It is expected to last about six weeks. He is being judged here on seven charges concerning financial fraud. He faces more than 100 years in jail.

“Was There Fraud or Was There Not?”

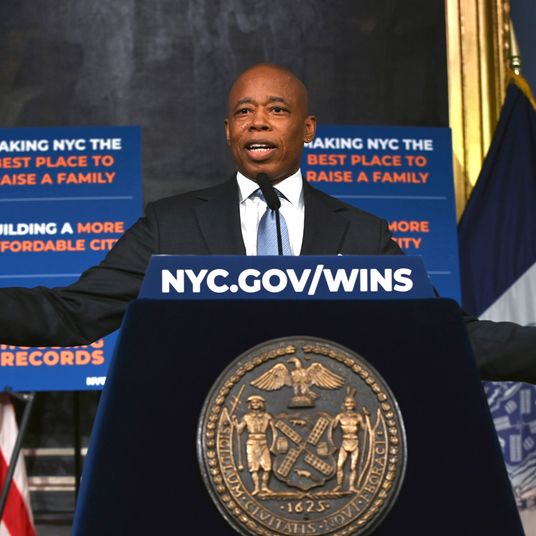

On the Thursday before the trial began, Bankman-Fried’s lawyers tried one more time to get their client out of jail. The judge is Lewis L. Kaplan — who, in a weird coincidence, will make his second appearance in the Court Appearances newsletter, having presided over the E. Jean Carroll trial. He took this last-ditch appeal in a relatively small but handsome wood-paneled courtroom on the 21st floor of 500 Pearl Street, rather than a larger ceremonial courtroom with more marble and greater seating.

Mark Cohen, an attorney for SBF, argued that his client needed more time to review the 1,300 exhibits, a volume made more daunting by their apparent complexity. Danielle Kudla, a prosecutor for the Justice Department, argued that he already had seven-and-a-half months to review before getting thrown back in jail, and anyway, he has extraordinary access to both computers and his lawyers in jail. Judge Kaplan in the end declined to set Bankman-Fried free. (He did allow more time for preparation.) Not only do defendants in complex drug cases prepare from court, he said, but Kaplan wasn’t convinced that this particular defendant wasn’t still a flight risk. As for all that complexity, he was incredulous. “The issues here are pretty straightforward,” he said. “Was there fraud or was there not?”

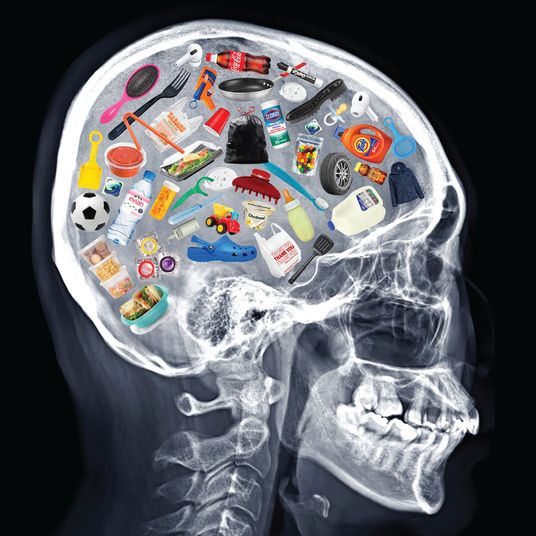

Lawyers sometimes talk about how The Law can be beautiful, and I doubt anything prettier than that was said at the hearing. But is that really all it boils down to? Bankman-Fried’s trial is, for those of us not in the court, about many things: the rot in cryptocurrency, the spinelessness of politicians, the glad-handing media, greed, sex, nerds, power, America. SBF himself is, despite the efficiency of his nickname, a figure of immensity. He is someone who made and lost more money than you could ever dream of, a figure capable of both moral clarity (a dedicated animal-rights activist who sought to eliminate poverty and nuclear war) and abject depravity (an accused witness tamperer and an apparently duplicitous character when it comes to his moral beliefs). So he contains multitudes — a kind of quantum object, always in motion, both one thing and another. But here, in court, he is being judged on very narrow criteria.

Isn’t the case a slam-dunk for the prosecution?

Did SBF knowingly build and use a backdoor into FTX’s code that gave his personal hedge fund the ability to borrow unlimited amounts of other people’s money? If the answer is yes, that’s fraud. (He is accused of many other instances of fraud and conspiracy, so this is by no means the only hurdle he needs to clear). In Sheelah Kolhatkar’s recent piece in The New Yorker, she writes that she had been grilling Bankman-Fried in his parents’ house with his mother and father flitting in and out of the kitchen when he said, and she’s paraphrasing: “Bankman-Fried was adamant, in my conversations with him, that prosecutors would not be able to produce any documents showing him authorizing the unlimited borrowing, because, he says, there are none.”

The specificity of this language implies that he has been trained to some degree to make this point. (Not only is he represented by many high-powered lawyers, but the publicist Risa Heller, who has represented Jeff Zucker and Jared Kushner, has been helping his parents.) Whether it’s true that he did not have a hand in the flow of money between these companies is something that a jury will decide.

This fits his overall strategy: Admit he screwed up, lean on how complicated and messy it all was, and insist he had good intentions all along.

There are any number of things that can support this. The utter size of this case is tremendous. There are millions of documents. Judge Kaplan referred to the volume of evidence as “a mountain.” Every transaction, every spreadsheet, every text, every word in a deposition can be used by a skilled attorney to demonstrate innocence or guilt. All these things introduce a risk that cuts both ways.

There are at least three cooperating witnesses for the government: former Alameda CEO (and SBF’s ex) Caroline Ellison, his former best friend and FTX co-founder Gary Wang, and former director of engineering at FTX Nishad Singh. (Ryan Salame, another former FTX executive, is reportedly not cooperating.) But just because they’ve pleaded guilty to charges of their own and are cooperating with the prosecution doesn’t mean that any one of them couldn’t say something that actually undermines the prosecution — or that they could change their mind at the last minute. (It’s rare, but these kinds of things do happen).

If SBF is correct that there really is no written evidence showing that he directed fraudulent transactions, the prosecution will have to work harder to make that case. In white-collar cases like this, that can be extraordinarily difficult.

All the Details

The charges: Sam Bankman-Fried is being tried on seven counts: two charges of wire fraud, two charges of conspiracy to commit wire fraud, then a charge each for conspiracy to commit securities fraud, commodities fraud, and money laundering.

The judge: Judge Lewis A. Kaplan was appointed to Manhattan federal court by Bill Clinton, and has overseen a striking number of cases that have found their way into the public discourse: Prince Andrew, Kevin Spacey, and Al-Qaida plotter Ahmed Ghailani.

The timeline: Jury selection begins on Tuesday, October 3. Opening statements should start the next day. The court currently expects to end the trial in mid-November, with prosecutors presenting for four or five weeks and the defense taking the stage for about a week.

The witnesses: Will SBF take the stand? It’s not clear. Lawyers declined to comment, and there has been no witness list released yet. However, Ellison, Singh, and Wang are likely to testify for the prosecution. (Salame may also be called to the stand, even though he apparently didn’t cut a deal). During the hearing Thursday, prosecutors mentioned that there were two more witnesses who still needed to finalize an immunity agreement, though their names weren’t made public. So, there may be a lot.

The consequences: In order for SBF to clear this trial, he needs to prevent a jury from coming to unanimous conclusions about all seven counts. But even then, he is not in the clear. The government expects to bring the remaining political corruption and money laundering charges in March 2024. He is also facing civil claims from the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, and many other unhappy private people and companies. Even if he wins, he could still find himself broke and barred from the financial industry.