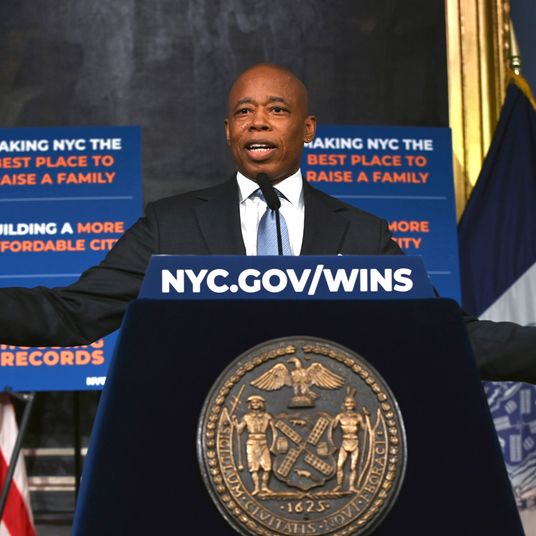

Two days after announcing a challenge to Mayor Eric Adams, State Senator Zellnor Myrie of Brooklyn was blunt about why he thinks New York needs a change at City Hall.

“I think there is a broad sense that the city is rudderless, that we are lacking in leadership, and that we need to go in a new direction,” he told me, building a case in smooth, complete paragraphs like the Ivy League–trained lawyer he is.

“We experienced an earthquake in the city and didn’t get a notification of that until half an hour after the fact,” he said, referencing last month’s 4.8 magnitude quake and the official notices that went out well after news organizations had reported the tremors. “We have had flooding in our subways and did not have a press conference on that until the middle of the day,” he said, recalling last fall’s torrential downpour that dumped nearly nine inches on the city. An investigation by the comptroller found the city had failed to properly prepare for the storm response, and Adams was faulted for holding a press conference two hours after Governor Kathy Hochul had declared a state of emergency.

“These are seemingly innocuous things in isolation,” Myrie told me. “But taken together, I think they paint a picture for New Yorkers that the Adams administration is not focused on governing and not focused on the basic necessities and services that we need.”

Myrie’s candidacy will focus on creating affordable housing and building universal after-school programs for every city kid who wants to be in one. His run crystallizes a high level of discontent New Yorkers have been expressing to pollsters for months. A January survey by Quinnipiac University showed Adams with a 28 percent approval rating — the lowest of any mayor since the school began polling the question in 1996. The New York Times grimly described how badly the city has soured on its mayor: “Roughly 58 percent of New Yorkers disapproved of Mr. Adams’s job as mayor, and the dissatisfaction was nearly across the board. A majority of those polled said that the mayor did not have strong leadership qualities, did not understand their problems and was not honest or trustworthy.”

A sampling by the conservative Manhattan Institute last month showed even worse results, with only 16 percent of likely voters saying they would pick Adams if the election were held now, compared with 62 percent who would prefer “someone else.” The institute noted, “In all five of the city’s boroughs, likely voters overwhelmingly disapprove of Adams’s job performance. Even in his strongest demographic, Black voters, Adams’s approval rating is net negative.”

Most politicians, in the face of these five-alarm-bell warnings a year before the 2025 primaries, would clean house, shake up their team, and try new approaches. Not Adams. The mayor regularly tells reporters his mantra is to “stay focused, no distractions, and grind,” suggesting that nothing about his approach to governing will change. This means Adams will continue to micromanage his administration: The mayor recently implemented a requirement that electronic forms be completed by anyone wanting to meet with a city commissioner — forms Adams says he personally reviews every morning.

We should expect to continue to see Adams lash out at perceived critics. He supports the high-ranking NYPD officers who routinely use the department’s official social-media accounts to attack judges, prosecutors, City Council members, student protesters, and members of the press. The mayor continues to duck sit-down interviews with political journalists, preferring the friendly embrace of Black and Caribbean entertainment programs (a strategy that backfired spectacularly when “The Breakfast Club,” a hip-hop show, brought in attorney and advocate Olayemi Olurin, who grilled Adams on criminal-justice issues).

Myrie’s candidacy will be a public reckoning over a growing pile of criticisms the Adams administration has deferred, denied, or ignored for the past two years, shortcomings that have strained the mayor’s relationships with parts of the city’s large governing class — the politicians, lobbyists, contractors, union leaders, editorial boards, corporate managers, grassroots activists, party bosses, civil-rights advocates, donors, faith leaders, and nonprofit executives who can make or break a candidate.

Many of these influential, politically active New Yorkers and their constituents want stability at City Hall and don’t see it coming from the Adams administration, says Myrie. “One week, they are proposing cuts to libraries, parks, and after-school programs. The next week, they are proposing cuts to pre-K and 3-K. And then the following week, they are proposing restorations to those very services,” he told me. “That is disorienting for our families. It’s disorienting to the people who provide those services. The expectation that New Yorkers have is not that their mayors be perfect but that their mayors at least have a handle on how to run the nuts and bolts of government. And I think in too many instances, that has not been the case.”

Myrie says he became convinced to jump in after months of hearing grumbling among municipal insiders. “What I have heard repeatedly has been that people are tired of the showmanship and really want results,” he said. “This boils down to people having confidence that their leaders are focused on making their lives better and that they’re relentlessly focused on that. Not showmanship. Not recorded applause at press conferences. Not staying to the wee hours of night at Zero Bond. But a relentless focus on making their lives better.”

The odds do not favor an upset by Myrie or Scott Stringer, the former comptroller who has also announced a candidacy. “I think the next mayor will be the person that people feel has the most fiscal sense, the grown-up in the room, the best vision and the best policy ideas,” Stringer told me earlier this year. Only two sitting New York mayors have lost a Democratic primary in the past half century: in 1989, when David Dinkins beat Ed Koch, and in 1977, when Koch led a crowded field to unseat Abe Beame.

On paper, Myrie — who represents the same Central Brooklyn State Senate district where Adams got his start — comes with some advantages. The district includes conservative Jewish parts of Crown Heights as well as parts of politically liberal Park Slope, giving Myrie insights and allies with key voting blocs. As the Black, Spanish-speaking son of immigrants from Costa Rica, Myrie’s Afro-Latino identity gives him roots in multiple communities.

But Myrie thinks the race won’t be decided by the usual ethnic and political calculations and maneuvering. “Most people are not watching every single move. They want to know if they can afford to stay in the city. They want to know they can send their kids to good schools,” he told me. “They want to know they can have affordable child care. They want to be able to send their kids to after-school programs so they can get some relief. These are the things people care about. They want clean streets, safe subways. All the other stuff is noise.”