After it was announced earlier this year that Samantha Power was leaving President Obama’s National Security Council, I e-mailed her to ask if she would grant an exit interview. Within the half-hour, she sent her regrets. “I think I’m going to have to pass at this stage, not least because—after getting reacquainted with my children—I may return to the administration, though haven’t made any decisions at this point,” Power wrote. “Sorry not to be more availing. As a former journalist, I know I should be the type you can count on.”

Now that Power has returned to the administration as (pending Senate confirmation) the U.N. ambassador, it’s her role as a former journalist that explains much of the excitement that has greeted her appointment in the press. Although America’s man (or woman) in Turtle Bay has often been an intellectual—from Arthur Goldberg to Daniel Patrick Moynihan to Jeane Kirkpatrick—we’ve never had an intellectual quite like Power, one whose dazzling first career was as a crusading, bearing-witness writer determined to make America live up to its ideals.

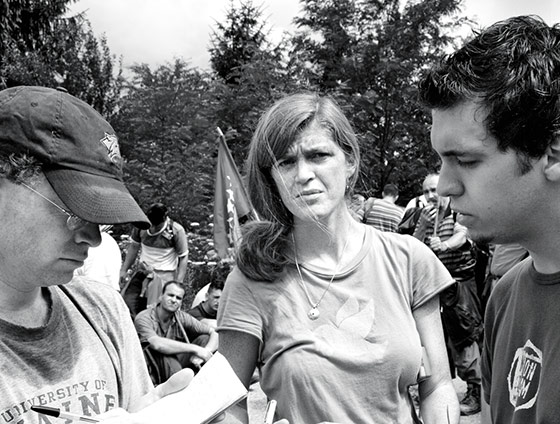

From the moment in 1993, when, fresh from Yale, she arrived in the Balkans to cover the conflict as a stringer for the Boston Globe, Power has been a sui generis figure in journalism. “She was a force of nature,” recalls Barbara Demick, who was in Sarajevo for the Philadelphia Inquirer and is now the Beijing bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times. Power spoke Bosnian. She harangued her editors for more column inches to describe the latest atrocity. The New York Times’ Roger Cohen remembers the night he lost a vodka-drinking contest to a Russian U.N. official and wound up passed out in the street, only to have Power carry him back to the Sarajevo Holiday Inn. More than anything, it was what Cohen calls the “fierce moral indignation” of Power’s war coverage that brought her acclaim.

She seemed destined for a storied career as a foreign correspondent, but instead she returned to the States to attend Harvard Law, then set up a human-rights center at the university. This provided her a perch to be even more vivid—and effective—with her writing. She contributed long, deeply reported articles on topics such as Rwanda and Darfur for publications like The Atlantic and The New Yorker. In 2002, she published her seminal book on genocide and American inaction, A Problem From Hell, which won the Pulitzer Prize. Although the book documented the moral failures of those in authority, it also celebrated the voices of the few officials who did try to prevent genocide. It was a thrilling though unlikely fantasy to imagine Power someday becoming one of them.

And then she was. Not long after Obama was elected to the Senate in 2004, he invited Power, whom he’d never met, to lunch so he could pick her brain about foreign policy. She soon took a leave from Harvard to work in his office and then on his presidential campaign. “She felt it wasn’t enough just to describe atrocity and the world’s broken response to it, which is what journalists do,” says The New Yorker’s Philip Gourevitch. “She felt the need to be much more involved in the system.”

She became not only a valued adviser but a crucial surrogate to the New York media intelligentsia: Obama and Power, two morally forthright individuals with uncommon writing talent, seemingly more comfortable in this town than Washington, who, together, would undo the foreign-policy disasters of the Bush years. As Power told Charlie Rose in 2007: “The very things that I would love about Barack and that you would love about Barack is that he is one of us. He’s a normal guy. He’s not a political animal.” But then in the heat of the Democratic-primary fight, in what she thought was an off-the-record conversation with a British journalist, Power branded Hillary Clinton “a monster.” She resigned from the campaign and went into the wilderness.

When Power later resurfaced as a member of Obama’s NSC, she’d learned her lesson and now viewed her old reporter friends more warily. “You have to understand how muzzled she is, how afraid she became of sticking her head up and getting it blown off,” says one. “That’s just the nature of the Obama White House. It’s almost as if her journalism and her advocacy were working against her. From the outside it was great, but from the inside she had to prove that she was a team player and could be trusted not to put her own template on everything.”

For Power, who loved nothing more than freewheeling dinner-party conversations with smart journalists, it was a difficult transformation. She complained to the writer Stacy Sullivan, a friend from covering the Balkans, that where she and her husband, Cass Sunstein, a Harvard Law professor who’d also gone to work for Obama, “once felt a whole gamut of emotions and used many adjectives to describe things; after they went into the administration, they assessed things on a simple grid of effective and not effective, respected and not respected. ‘How was your day, honey?’ ‘It was great, I was effective and respected.’ ” Notwithstanding her successful efforts to persuade Obama to intervene in Libya, her old colleagues believe the substance of her job—namely, dealing with a president averse to foreign entanglements—has taken a toll on her, too. “I just think it’s very hard to look at the Obama foreign policy and say that’s a human-rights record that Samantha Power would be proud of,” says one.

As U.N. ambassador, Power will once again be in the spotlight. But it’s not clear what she’ll do with it. “It’s this classic dilemma: One of the foremost writers on the problem of genocide now will be on the very front line of diplomatic efforts to prevent further genocide,” says Bloomberg View’s Jeffrey Goldberg. It would be easy to imagine her turning the ambassador’s residence—a penthouse at the Waldorf-Astoria—into a high-minded salon, but that is probably just another fantasy. “I don’t think she’s going to be having bull sessions with correspondents,” says Gourevitch. “I think it’s much more likely she’ll be doing the Waldorf meetings with the heads of UNHCR and the IAEA and the Jordanian ambassador and a couple of undersecretary generals and the deputy chief of mission from Dagestan.”

The truth is, the Power who wrote A Problem From Hell is not—and can’t be—the same Power now responsible for solving that problem. Goldberg suspects that she will have to “rein in her essential Samantha-ness working for a president who’s not quite as eager to dragon slay.” The chilling of friendships goes both ways. “I’m under no illusions. She’s the U.N. ambassador. And if there are things to be critical about, we’ll be critical about them,” says David Remnick, who, during Power’s brief hiatus from the administration, tried to get her to return to writing for The New Yorker. “It’s very stupid to be sentimental about it. That would be an abrogation of the job.”

First, Power needs to get confirmed. When I e-mailed her last week, I told her that, given her upcoming hearings, I assumed she wouldn’t want to talk to me. She replied, “Are you kidding? I would of course love to talk to you—I am just denied by others that privilege!”

Have good intel? Send tips to [email protected].