This review originally appeared in New York magazine.

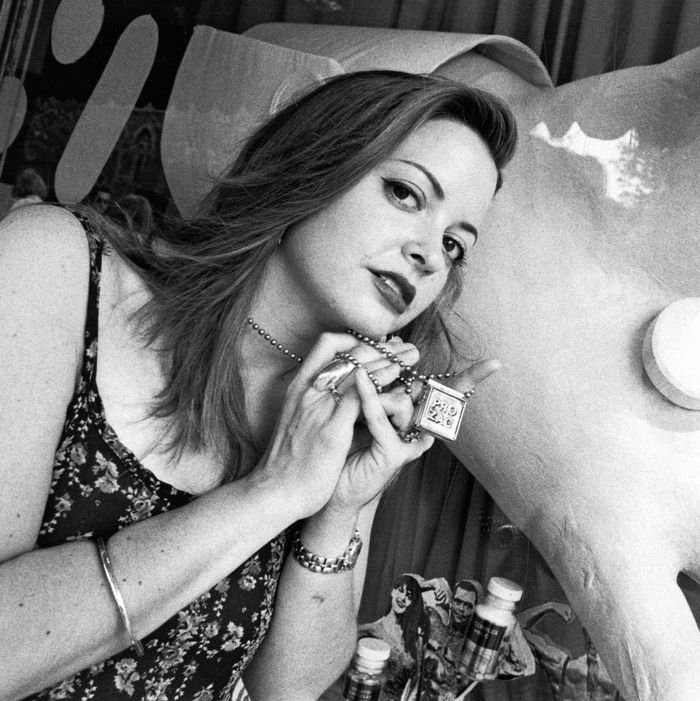

Even the title of Elizabeth WurtzelÔÇÖs Prozac Nation: Young and Depressed in America sounds like an excuse. With more than a hint of grandiose self-pity (and some MTV-style marketing savvy), it strives to position its author as a poster child for a putative bluesy youthquake, pretending to offer us not just the memoir of one womanÔÇÖs early sorrows but a newsworthy generational complaint. WeÔÇÖre encouraged to view WurtzelÔÇÖs woes as symptomatic: as a possible Newsweek feature story first and an autobiography second.

But for all Prozac NationÔÇÖs gestures toward the generational, itÔÇÖs really a work of singular self-absorption, and its painÔÇöhowever real it may have been in lifeÔÇöoften seems fake on the page. Depression is not so much described as usedÔÇöto garner sympathy and admiration. Like a college student wondering aloud about how much she can drink and still get AÔÇÖs, Wurtzel regards her emotional destitution as something of a marvel.

The long moan begins with WurtzelÔÇÖs parents, who split when she was 2. The language is exaggerated, stretched with adjectival filler. ÔÇ£I got two parents who were endlessly at odds with each other, and all they gave me was an empty foundation that split down the middle of my empty, anguished self.ÔÇØ Her footloose father leaves little Elizabeth with her buttoned-up, Republican mother and goes on his merry way, rarely to be seen afterward. At first, things are all right. Elizabeth is a cheerful, eager studentÔÇöeven a prodigy. Then comes the mysterious breakdown. The good girl, growing vaguely ashamed, plays at being a bad girl, experimenting with self-mutilation. This is described in one of the bookÔÇÖs all too frequent italicized interludesÔÇöthe prose equivalents of movie dream sequences, when the screen goes all hazy around the edges. ÔÇ£I took the nail file, found its sharp edge, and ran it across my lower leg, watching a red line of blood appear across my skinÔǪ I did not, you see, want to kill myself. Not at that time, anyway. But I wanted to know that if need be, if the desperation got so terribly bad, I could inflict harm on my body. And I could.ÔÇØ┬á

The scene shifts to Harvard, where Wurtzels psychic wounds begin to ooze anew. She cuts classes, loves and loses preppy men, and takes large amounts of Ecstasy, describing this last activity in a sentence designed to show off her rock-and-roll side (she was once New Yorks rock-music critic) and her liberal-arts chops too: When I was rushing on that Ecstatic run, all was quiet on the western front of my mind. Some sort of crisis occurs when Wurtzel, sleeping late after tripping, misses her grandparents visit to campus. As she catalogues her collapses and trips to the ER, the bragging tone becomes unmistakable. Harvard was full of nut casesStill, no ones desperation came close to matching mine Only I seemed to be left behind, crying and screaming about wanting more, wanting my money back, wanting some satisfaction, wanting to feel something. About here, a book that has thus far been only intermittently tolerable becomes almost unbearable.

Wurtzel associates herself with accomplished female literary depressives gone before: And Im starting to wonder if I might not be one of those people like Anne Sexton or Sylvia Plath who are just better off dead.  Perhaps, I, too, will die young and sad, a corpse with her head in the oven. Even so, theres not a lot of shape to Prozac Nation, which suggests Wurtzel chose to ignore the formal lesson of her hero Plaths poetry: Hysteria has more impact when its contained. Sadness in art needs strict borders to press up against; otherwise, its just a muddy overflow. Prozac Nation is at its best when Wurtzel tells her stories straight, in the harness of traditional narrative form, instead of letting them swell to fill the infinite cosmic cavities of her pain. In what was for me the books truest episode, she calls up an almost total stranger, a man, when shes in need of late-night sympathy. Surprisingly, a relationship develops based on sick emotional synergies, and Wurtzel details its beginning, middle, and end with clarity and elegance. I became rambunctious with tears every time I left Rafe. I cried on the bus from Providence to Boston. I cried on the T from Boston to CambridgeI cried when I arrived home and found that my roommates had all gone to sleep and there was no one to cry to.

ItÔÇÖs too bad that such moments of shapely truth-telling are crowded out by sorrowful arias and speculative psychosocial analysis. Wurtzel the author and Wurtzel the character function best when theyÔÇÖre furthest apart, but instead they keep on messily merging. What could have been a pointed roman ├á clef about an especially trying young woman (and probably would have been written as such in simpler, less confessional, less syndrome-conscious times) lies buried in self-obsessed case study.