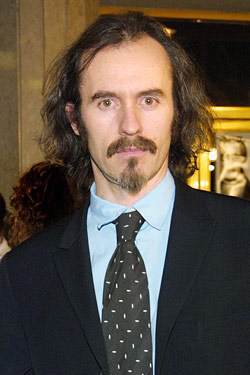

Stephen Dillane, a staple of arty European cinema in the Jeremy Irons mold, has high standards. He starred in Michael WinterbottomÔÇÖs Welcome to Sarajevo, played Thomas Jefferson in John Adams, and won a Tony as the playwright at the heart of Tom StoppardÔÇÖs The Real Thing. Now heÔÇÖs decided to slum it ÔÇö or so he tells it ÔÇö by deigning to play two Shakespeare roles in repertory for BAMÔÇÖs Bridge Project: melancholy Jacques in the already running As You Like It and, starting February 14, Prospero in The Tempest.

YouÔÇÖve done an award-winning Hamlet and a one-man version of Macbeth. Is The Tempest a challenge?

I donÔÇÖt think IÔÇÖve ever seen a production of it thatÔÇÖs been particularly satisfactory to my way of thinking. So IÔÇÖve had a curiosity about it. I donÔÇÖt know if itÔÇÖs even playable, but it certainly contains some kind of mystery that I find compelling.

Wait a minute ÔÇö this play been done for 400 years. YouÔÇÖre not saying that it canÔÇÖt be produced?

I withhold judgment. But I think a difficulty with trying to communicate both visually and aurally at the same time is quite common in Shakespeare. But we want to make a living, so one is always compromised. You can continue to operate in a certain area while still questioning the validity of it, and indeed I think the conversation exists within the rehearsal room.

Really? Does Sam Mendes want to talk about how itÔÇÖs impossible to stage The Tempest?

I think he has a certain curiosity about it. YouÔÇÖd have to ask him.

How about As You Like It? ThatÔÇÖs more of a crowd-pleaser.

IÔÇÖm increasingly impressed with it, but itÔÇÖs a very difficult play to make sing. It doesnÔÇÖt contain the sort of metaphysical mystery of The Tempest, thatÔÇÖs for certain. But there are other attractions.

ThatÔÇÖs a pretty gloomy outlook ÔÇö maybe appropriately so, because the characters in As You Like It are always talking about how melancholy Jacques is. Do you identify with him?

Am I melancholy? I certainly have moments. I like to think thereÔÇÖs a capacity for joy as well. Sometimes you see people who appear in their everyday life to be very cheerful who are able to play melancholia very well.

YouÔÇÖve been compared to brooding actors like Jeremy Irons and Daniel Day-Lewis, yet youÔÇÖve repeatedly spoken out against overacting.

I have to phrase this perfectly: IÔÇÖm just not convinced that the attention we give to creating what we think of as a character isnÔÇÖt actually quite often the means by which an actor overcomes his own terror of standing there onstage and creating a mask to hide behind.

Okay, but charismatic acting wins awards and gets people noticed. Do you think an understated approach has hurt your career?

I havenÔÇÖt been put in a position where IÔÇÖve had to take on a hugely charismatic role which might have made me famous. Whether that means my career has suffered or not, IÔÇÖm not sure. I donÔÇÖt think I lack an ego, thatÔÇÖs for sure, and I donÔÇÖt think anybody who knows me would be sure that I did, either.