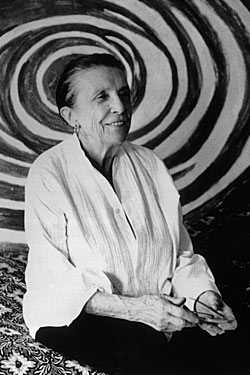

Robert Mapplethorpe’s iconic 1982 portrait of Louise Bourgeois, who died yesterday at 98, speaks volumes about Bourgeois’s free-spiritedness, grace, tenacity, and the kinky perversity of her work. In it, the 71-year-old sculptress looks like a shaman seductress, one of Munch’s vampiric castration queens, a maker of voodoo dolls, and a diva grandmother rolled into one. Under her arm she casually cradles her 23-inch long, seven-inch circumference latex-over-plaster sculpture of a phallus, Fillette (1968). In French the term means “helpless little girl.” While Bourgeois was no little girl, there’s something radically vulnerable about how she’s holding the work — she almost seems to pull back the sculpture’s foreskin and give the thing a little tickle. Bourgeois said this gnarly abstract penis, with ovular testicles and a hook at the top, was “the shape of my husband, the shape of the children” (she had three sons). “I wanted to represent something I loved,” she said. “I obviously loved representing a little penis.” Little? Anyway, as Bourgeois later said, “It’s very complicated.” Indeed it was. As she said, “I have nothing against the penis. It’s the wearer.”

For over seven decades, but in especially mordant, tough, and compelling ways over the last 30 years of her career, Bourgeois — perhaps the last twisted sphinx of surrealistic psychology, and the final vehicle of Abstract Expressionistic seriousness — turned the stuff of childhood trauma, Oedipal desire, raging fury, and human sexuality into moving sculptures.

She often recalled her adulterous, psychologically abusive father. (He had an affair with her English governess, which her mother was unable to even acknowledge.) She told of how he regaled dinner guests with stories of how unattractive she was, and ridiculed her large breasts. It’s perhaps not surprising, then, to find abstract images of birth, death, fear, and sex in Bourgeois’s work: vivisectioned vaginas made of marble, drawings of women with houses for heads, latex dresses made of breasts. One of her installations includes an embroidered handkerchief with the words, “I have been to hell and back and let me tell you it was wonderful.” Another work, The Destruction of the Father, features mounds and what looks like the jaw of a dinosaur. In the Guggenheim’s catalog for her retrospective there, Bourgeois is quoted describing an imaginary situation in which she, with her family, threw her father “onto the table and pulled his arms and legs apart — dismembered him … ate him up … It is a fantasy but sometimes the fantasy is lived.” For the “lived” part of those fantasies, immerse yourself in her miniature stuffed figurines, many of them housed in glass vitrines, which seem to kill, attack, or make love to one another. She reveled in infernal scenes of headless bodies, big spiders that dominated city plazas like avenging angels, and otherworldly mothers.

After not paying much attention to her work, even dismissing it as latter-day surrealism, I finally became a Bourgeois fan in the eighties. Her images, materiality, scale, and surfaces seemed to get braver and more commanding. The theatricality, surrealism, and Abstract Expressionist angst seemed to become more mysterious, bizarre, and disarming. Although I never liked the spiders, and her pink wooden figures still strike me as derivative, her narratives came totally alive with an almost Kafkaesque darkness and urgency. Her works became horror comedies of sex, memory, and living within the confines of a body. She was metamorphosing figures in ways that made them feel at the service of forces greater than those of humanity; they became puppets of the gods, expressing a sort of cosmic will. Bourgeois’s feminism had mutated into a simultaneously heroic and personal state. Where many artists who incorporate their biographies become slaves to them, and flog them in cloying ways, Bourgeois was always removed and skeptical, as filled with anger as she was with wit and incredulity.