Kings of Leon is a hugely successful band. (I’ll spare you all the “platinums” and “millions” let’s just say their last album, Only by the Night, sold like nuts.) They’re also the kind of band your rock-geek friends probably roll their eyes at. And if you happen to enjoy them the sales numbers indicate a pretty good probability that you might! you probably respond to that eye-rolling with more eye-rolling: What, music geeks can’t like something just because it’s popular? Too mainstream to be cool?

That’s how those arguments usually go, anyway. But I don’t think it’s really about popularity. There’s an interesting difference that often crops up between the music that music geeks respond to and the music that the real world responds to. Music geeks tend to think comparatively — they’re interested in what one act is offering, or accomplishing, that isn’t getting accomplished by anyone else. Whereas normal human beings, a lot of the time, turn to something like a rock band to get an experience called “rock” — this common, understandable thing the world enjoys. They don’t show up in stadiums to see Kings of Leon subvert or reshape the traditions of rock, just to deliver on it.

And Radio Vulture should disclose that it is, by its nature, written by someone who thinks more like a music geek.

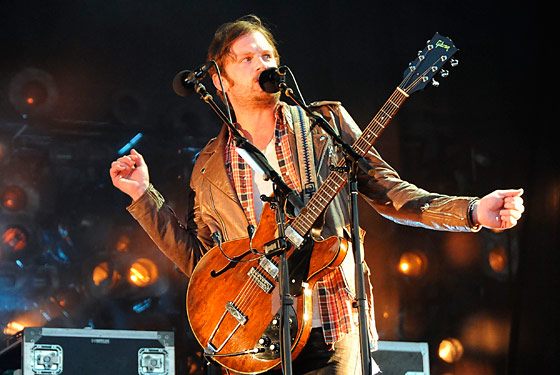

I’m impressed, though, by how well Kings of Leon has done by providing people with some kind of cornerstone “rock” experience. The things they deliver on are utilitarian, functional: stadium-size music with enough alt-rock in it to seem modern, plus a dash of the throwback yowling most bands are too fashionable to mess with anymore. Sometimes they seem less like a real rock band and more like a screenwriter’s idea of a rock band in a so-so movie. It’s even wrapped into their biography. In the early scenes, they’re just a southern preacher’s three sons, starting a band with one of their cousins. Their lyrics, too many of which seem to have been ghostwritten by singer Caleb Followill’s genitals, grab at exactly the kinds of broad archetypes that’d make up an onscreen personal life. (On their new album, his chronicle of puffed-up male ego finally reaches its destination, with the line “she tells me I’ve got a big ol’ dick.”) Forty minutes into the film, their southern-style sound is taking off in the U.K. — and then comes 2008’s Only by the Night, and the dizzying montage where they sell millions of records, rise to fame, hear every Tom, Dick, and Harry singing their songs at the bar, and …

… well, then comes the part — perfectly true to script — where the tensions and burdens emerge, and everyone gets a little surly. Sneery things are said in interviews. Caleb starts calling the Grammy-winning single “Sex on Fire” a “piece of shit,” cozying up to his dedicated fans at the expense of all the new folks who just, you know, paid him cash money to hear it. The band starts bickering with the universe.

The main thing I’m trying to figure out about the new LP, Come Around Sundown, is whether this has made Kings of Leon more or less interesting. Because this is the one where they grumble, sitting around a windowless studio in New York, surrounded by the hustle and bustle of mild stardom, thinking back on those joyous early scenes where everything was so simple and pure. That feeling gives us stuff like “Back Down South,” not the most interesting song in the world. But I’m pretty sure it’s also how we get something like the video for “Radioactive,” in which the band awkwardly cavorts with dozens of black children at what looks like a post-church barbecue from somewhere around the civil-rights era. “It’s in the water,” Caleb wails — “it’s where you came from!” And that’s interesting, in its way: If you can watch it without laughing in amazement, you’re either a better person than me or you slept through sensitivity training. But again, it’s the band earnestly reaching out to the biggest archetypes going — it just so happens that they accidentally grabbed hold of a creepy one.

Part of what makes Kings of Leon work is that their broad archetypes, stadium choruses, and full-throated vocals aren’t just shamelessly courting fame — it’s more like the band is genuinely and earnestly invested in that straight-from-a-movie vision of themselves and their music. If there’s not a lot to say about Come Around Sundown, it’s because it’s delivering on precisely the archetypes and sounds you’d expect from this part of the movie. Most bands start off thinking of their audience as their people, an extension of themselves — but if you get this big, you wind up speaking straight to the hearts of folks you might not have wanted anything to do with. You start feeling distant. And then here comes the scene where you look in and back: start thinking about where you originally came from, start thinking about buying a big patch of land back there and just getting away from it all and getting back to the music, man, and home, man, and … that’s about when you make this album.