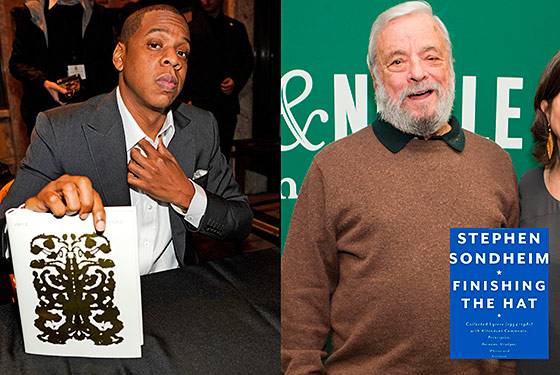

The past month has seen the publication of not one but two books by giants of American music, offering interpretations and annotation alongside their lyrics. Yet the careers they delineate could not be more different: Stephen SondheimÔÇÖs Finishing the Hat gets off the ground via collaboration with Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins, and Jay-ZÔÇÖs Decoded begins with tales of the vicious, druggy life around the Marcy projects in Brooklyn. New YorkÔÇÖs pop critic, Nitsuh Abebe, and senior editor (and Sondheim obsessive) Christopher Bonanos met up via instant messenger to do a little comparative-lit exercise.

N.A.: So, Stephen Sondheim and Shawn Carter ÔÇö two books, two worlds. How shall we come at this?

C.B.: Well, given the magazine we work for, I thought IÔÇÖd start by noting how extremely New Yorky these two guys are ÔÇö even if their lives have very little in common.

N.A.: I never feel New Yorky enough to judge those things, but I certainly see what you mean. And they both wind up at the center of very New YorkÔÇôbased art forms ÔÇö musical theater and rap.

C.B.: One as his idiom is growing into something that dominates the world, and the other  well, lets be nice and say its already peaked.

N.A.: Sondheim claims that ÔÇ£in 1952, nobody was taking musicals seriously,ÔÇØ so I suppose he feels like he was involved in a certain peak, too.

C.B.: Yes. And that itÔÇÖs gone: ThereÔÇÖs that passage flatly saying that musical theater no longer reflects the immediacy of our world.

N.A.: I love the equivalences you can draw out of it. In this analogy, Oscar Hammerstein II becomes Big Daddy Kane, and Leonard Bernstein becomes the Notorious B.I.G. And instead of passing phrases like ÔÇ£everythingÔÇÖs coming up rosesÔÇØ into the language, itÔÇÖs lines like ÔÇ£sensitive thugs, you all need hugs.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs funny, though, how Jay-Z ÔÇö whoÔÇÖs sort of an elder statesman in a hugely popular and lucrative global art ÔÇö is offering this almost apologetic justification of it, a polite argument that thereÔÇÖs a craft involved. Whereas Sondheim, who admits the age of musicals is past, is so imperious and fussy about the craft of them!

C.B.: That struck me, too. Probably because nobody is arguing (anymore) that a Broadway musical, especially one of SondheimÔÇÖs, is not art, but plenty of people still do not acknowledge rap as art or even craft.

N.A.: Yes. I think thatÔÇÖs one of the problems with the Jay-Z book, actually. The main text is a great ÔÇö sneakily great! ÔÇö beginnerÔÇÖs window into the mentality and concerns of rap, or at least Jay-ZÔÇÖs variety of rap. But the way he annotates his lyrics gets a little beginner-level, too. He winds up explaining things that anyone whoÔÇÖs ever heard of Jay-Z will already know. And some that anyone who can read will already know ÔÇö I mean, he explains why using ÔÇ£breadÔÇØ and ÔÇ£toastÔÇØ in the same line is crafty of him, and how George W. BushÔÇÖs last name has a secret other meaning. (Referring to it as a ÔÇ£homonymÔÇØ makes this sound a lot more clever than it actually is.)

C.B.: Though I will say that, as a neophyte when it comes to rap lyrics, I was struck by one thing. I still have the idea that a certain amount of rap is improvised at the mike, in that street-corner-throwdown way. And seeing that he actually rewrites and reconsiders as much as he does surprised me. ItÔÇÖs more like Kerouac ÔÇö he used to say ÔÇ£first thought best thought, always,ÔÇØ but then heÔÇÖd go quietly edit his drafts.

N.A.: Rap gets far more crafted than lots of people assume. But a lot of it happens in a rapperÔÇÖs memory, because it still wants to feel like itÔÇÖs coming straight out of someoneÔÇÖs mind ÔÇö thatÔÇÖs part of the magic of it. I suppose musical theater runs into the same challenge: trying to make these perfect lines seem like theyÔÇÖre just naturally leaping from a characterÔÇÖs brain and situation.

C.B.: Which brings us to a nice question: What do you suppose each of these authors would think of the other?

N.A.: Well, Sondheim is nothing if not dedicated to his craft ÔÇö he spends a lot of his text rethinking single words and rhymes in lyrics he wrote decades ago ÔÇö which I think would impress any craftsman.

C.B.: True. They both love rhymes, but they barely define a rhyme the same way. Sondheim is fastidious about ÔÇ£near-rhymes,ÔÇØ and Jay-Z just wants flow. He doesnÔÇÖt object to a nifty pairing like ÔÇ£settleÔÇØ/ÔÇØghetto,ÔÇØ which wouldnÔÇÖt even make it onto a rough draft for Sondheim.

N.A.: And theyre nearly a true rhyme on record! I worry what Sondheim would think about Jay-Z. He says at one point that he considered the characters in West Side Story naturally inarticulate, which makes it sound like he isnt too intrigued by the basic, informal linguistic intelligence of other people. It made me think of Damon Runyon, a writer who pulled his entire style from the native language west of midtown, not too many decades earlier  and of course rap, later. His commentary on other lyricists, too  its far more concerned with precision of craft, and not overall effect. Nearly every one of his summaries of other writers includes a line like if this seems like nitpicking  

C.B.: True, though (to be fair) the West Side Story characters are supposed to be native Spanish speakers. I think his point is not that theyÔÇÖd be so much inarticulate as that their English would be much more basic than his rather poetic lyrics.

N.A.: Or theyÔÇÖd be inventing their own lively hybrids!

C.B.: You make a good point. And it brings up something a little surprising: Jay-Z is very generous when he talks about other rappersÔÇÖ work. Sondheim is pretty bilious about other lyricists, and even harder on himself. He is incredibly dissatisfied, to the point where it seems vaguely pathological, almost self-loathing.

N.A.: And really fixated on formal perfection! Early in the book, he spends a while arguing with a quote from an anonymous lyricist who says Im just a believer in feelings that come across. But Sondheim says the craft is supposed to serve the feeling  he seems to argue that you should never have to disrupt the form to get an emotional effect. That there should always be a way to do it within the form, and not finding that way is just plain laziness. In his defense, though, as far as biliousness goes, he does adopt a rule of only speaking ill of the dead. (Jay-Z doesnt really have that option, since hip-hop is awfully fond of dead legends.) Or, well  the dead and critics.

C.B.: Oh my God, yes! ThereÔÇÖs something these two guys have in common: They hate music critics.

N.A.: Yes! Jay-Zs a little kinder  he just seems confused by the whole notion of criticism, like  Why are you spending your life talking about what other people do? Sondheim actively considers critics ignorant and unworthy of commenting on his craft. I will say that, even as a critic, I agree with him on one front: He says the general idea is that anyone is qualified to talk about music. And hes correct: That is in fact often the idea. I dont know that its a terrible idea, but its bothersome if you care about the craft of music-and-lyrics, especially as much as he does.

C.B.: Which points out one important way in which these artists completely diverge. Sondheim is not writing lyrics that he himself will perform. Most rappersÔÇÖ output, including Jay-ZÔÇÖs, is about themselves.

N.A.: Well, I donÔÇÖt know that itÔÇÖs strictly about themselves ÔÇö thereÔÇÖs a whole subtle thing about personas and characters going on inside it, acting out different possible ways of being. But yeah, SondheimÔÇÖs doing service to specific characters other people created.

C.B.: Come to think of it, yeah, Jay-Z says that directly: ÔÇ£What the rapper is doing is creating a character that, if youÔÇÖre lucky, you find out about more and more from song to song.ÔÇØ Whereas Sondheim has repeated emphatically that he is not Bobby from Company, or George in Sunday in the Park.

N.A.: SondheimÔÇÖs also using language to try to distinguish different characters in different milieus ÔÇö whereas Jay-ZÔÇÖs more often suggesting that all milieus are basically the same, and you can learn everything you need to know about them by selling crack for a while.

C.B.: I hear Sondheim tried that, after Merrily We Roll Along flopped. Guy needed some dough.

N.A.: Ha ÔÇö honestly, given the crafts they pay the most detailed attention to, these two could collaborate on one hell of a musical about drug dealers.

C.B.: ItÔÇÖs not out of the question. If Sondheim is perverse enough to write a musical about presidential assassins, why not? Do you think Jay-Z would have it in him to write theatrical material? Or that heÔÇÖd ever want to?

N.A.: Well, thereÔÇÖs not really Jay-Z money in it, is there? Who knows, though: Of all the rappers to one day have a jukebox musical, heÔÇÖs probably near the top of the list. Although the rights situation might get complicated for ÔÇ£Hard Knock LifeÔÇ£ÔÇÿs Annie sample.

C.B.: Its a financial gamble, for sure  but if you do hit it big, you hit it very big. The Lion King, over a decade, has taken in something like $500 million at the box office. [UPDATE: Disney tells us its $730 million in New York, $4 billion worldwide.] Plus touring companies, Vegas productions, cast-album sales, blah blah 

N.A.: If youÔÇÖre gonna take the kids to learn about stash houses from any one rapper, it should be Jay-Z. ThatÔÇÖs actually a lot of whatÔÇÖs interesting about him! Some rappers get older and become industry vets; others turn into actors or pop-culture icons, like Ice Cube or Snoop Dogg. Whereas Jay-ZÔÇÖs worked on becoming the kind of upper-echelon business titan who gets to do interviews with Warren Buffett, or have book launches at the New York Public Library. Not an entertainer but a CEO. It makes him a little comical to some, when heÔÇÖs rapping ÔÇö sometimes he rhymes about staying on top like heÔÇÖs shooing kids off his lawn ÔÇö but that seems like part of the reason this book exists: HeÔÇÖs the first big rapper to get taken seriously in quite that way. Which is also why the book keeps reminding people of his starting point ÔÇö it works hard to impress on the reader that heÔÇÖs still forever coming from the standpoint of writing rhymes on brown paper bags while working a street corner and watching his back. And thatÔÇÖs allegedly why heÔÇÖs still talking about that while appearing on the cover of Forbes, etc.

C.B.: Has Jay-Z ever had a flat-out flop? Because Sondheim has, more than once, and it seems to gnaw at him, especially Merrily We Roll Along. (HeÔÇÖs right to be bugged about it, too ÔÇö itÔÇÖs a much better show than people thought at the time.) Whereas the Jay-Z story, at least as presented here, seems to be a pure rise, onward and upward and off to Beyonc├®.

N.A.: In a lot of ways, it really has been ÔÇö I donÔÇÖt think heÔÇÖs ever had an album not go platinum. I think heÔÇÖs had the usual shape of a successful pop career, where he was incredibly vital and exciting for a few records, then turned into the kind of reliable hit-maker who keeps selling records, seeming ÔÇ£biggerÔÇØ and more familiar and more central to the mainstream, even if his most definitive work is behind him. There have been some lower-performing Items in there, but not much youÔÇÖd call a huge failure. (Besides, ever since he ÔÇ£retired,ÔÇØ itÔÇÖs all just an encore.) Is it possible SondheimÔÇÖs so attached to formal craft because he doesnÔÇÖt have that single-handed control over ÔÇ£success?ÔÇØ

C.B.: As in, he has to hold up his end of the bargain, because others (director, book writer, etc.) might not deliver? Or, conversely, that he canÔÇÖt let them down?

N.A.: And he canÔÇÖt say ÔÇ£screw the off rhymes, IÔÇÖm making moneyÔÇØ ÔÇö the only take-home he can be completely sure of is that he did his part ÔÇ£right.ÔÇØ You know far, far more than I do about him, so I wanted to ask: Do you think he paid much attention to popular music since, say, the eighties or so?

C.B.: If I had to guess, I would say no. I suspect he is not inherently hostile to hip-hop ÔÇö from what I have heard, heÔÇÖs often generous to songwriters who care about language, especially young people ÔÇö but I canÔÇÖt imagine that hip-hop speaks to him much. Though I will say that thereÔÇÖs a vocal riff in Into the Woods, from 1987, that sounds like heÔÇÖd been paying attention to rap music.

N.A.: He does say ÔÇ£playing with words for the sheer pleasure of it is now considered elitist and trivial,ÔÇØ which makes me wonder how heÔÇÖd feel about lots of things. ThereÔÇÖs plenty of mildly elitist hip-hop thatÔÇÖs almost nothing but playing with words ÔÇö plus a few indie songwriters, like Stephin Merritt, who design rhymes the same way Sondheim likes. Though I think Merritt prefers Cole Porter.