Walking into comedian Anthony Jeselnik’s home, a two-floor Hollywood apartment with wall-size windows, the first thing I notice is a large-format photograph hanging by his sofa. The photograph is from artist Rachel Hulin’s Flying series, an image called Flight of the Scholar. It depicts a toddler in midair at the top of an imposing library staircase. He’s gazing upward, expression blank, his body at an off-kilter diagonal. Much of the work in Flying is placidly surrealist; they’re images of Hulin’s young son floating, unsupported, in various dreamlike spaces. Seen with her other work, Flight of the Scholar looks like part of a fairy tale. On its own, displayed in Jeselnik’s apartment, it looks like a huge photo of a kid who’s about to take a catastrophic fall down the stairs. It’s the first piece he points to when I ask him to tell me about the art he has in his home. He’d seen the Flying series online, and Scholar is his favorite, he says, because “that kid is going down.”

Jeselnik has built a long and successful career telling the darkest, most disturbing jokes in stand-up comedy, and his new Netflix special, Bones and All, out November 26, is the result of 20 years on the job. Onstage, he plays a supervillain — the kind of guy who can look straight out at an audience, tell a joke about pedophilia or murdered children, and barely flinch when the crowd groans in dismay. His jokes are obvious creations, full of cardboard-standee-style “my father” or “my brother-in-law” or “last week, I saw …” setups, but each one is designed to provide a fine-tuned calibration of the most surprising, offensive punch line possible. From his 2013 special, Caligula: “A month ago, some kids in my neighborhood were playing hide-and-go-seek, and one of them ended up in an abandoned refrigerator. It’s all anybody talked about for weeks. I said, ‘Who cares? How many kids do you know who get to die a winner?’” From 2015’s Thoughts and Prayers: “When I was a kid, my parents said they had to have a gun: ‘Gotta have a gun to protect our five children.’ Of course, they eventually got rid of it. To protect their four children.” “Last week, I saw a pregnant woman get hit by a bus,” begins one of the jokes in Bones and All. “Or, as I like to call it, a gender-reveal party.”

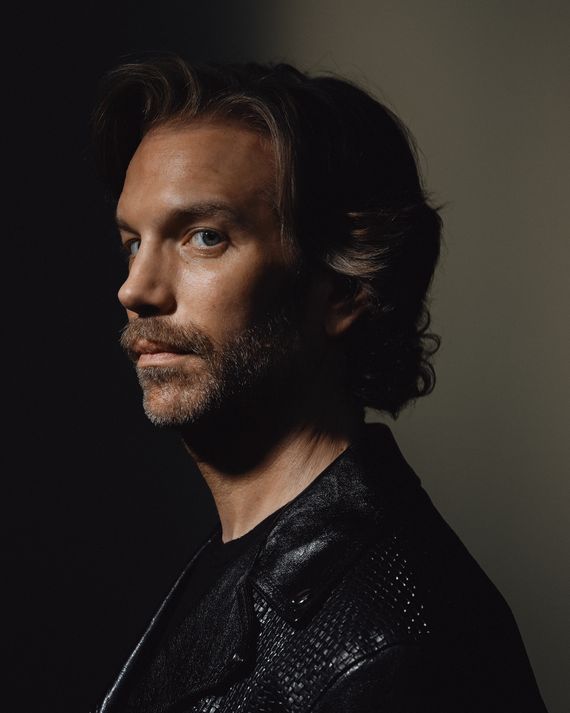

In his stand-up, he’s both evil and arrogant, and the whole package is presented with the deliberative pacing of a meditation app. His stage presence is coolly predatory, emphasized by his leather-jacket-and-jeans look, wolflike features, and the measured way he moves. Comedian Sarah Silverman likens it to professional wrestling: “He’s the heel. And he takes it and makes it really highbrow.” But underneath that performance, Silverman acknowledges that Jeselnik’s act has an unnervingly unknowable quality to it. His first breakout performances were in roasts, especially the Comedy Central roasts of Donald Trump and Charlie Sheen in 2011. “The conceit of the roast is that it’s friends who adore each other tearing each other apart. That’s not Anthony,” Silverman says. Even in those early performances, before Jeselnik was a well-known comedic act, he approaches the podium with none of the genial, buddy-buddy glee of the other participants. He is calm, professional, and dispassionate. Roasts are designed to have the pretense of meanness, but for Jeselnik, Silverman says, “the audience is also laughing because they suspect it might be true.”

Jeselnik’s persona has remained remarkably consistent over the course of his career, and he has no interest in changing it. “It is not a defense mechanism,” he says. “It is an offense mechanism.” He’s released three hourlong comedy specials and hosted multiple series (Last Comic Standing, Comedy Central’s The Jeselnik Offensive and Good Talk With Anthony Jeselnik). He sells out shows in the U.S. and abroad, with crowds that fill the Sydney Opera House and come expressly to enjoy his prince-of-darkness bit. He does not care for comedians who expose their flaws for public ridicule, and his allergy to self-deprecation has hardened into a worldview. “I’m not letting you laugh at me. I’m perfect,” he says. Sitting in his apartment, an hour into a conversation about comedic personas and what audiences want from a comedian, I ask him about Nanette, in which Hannah Gadsby describes their comedy career as realizing they’ve been punching themselves in the face. “You wrote those jokes,” Jeselnik says. “You made this act. I don’t feel bad for you. I get that you’re saying that you don’t want to do that anymore, but also, you never had to.”

It’s easy to mistake many comedians’ acts as representative of their private selves. Jim Gaffigan plays up the affable dad; Ali Wong is the snappish, sexually aggressive mom. Their comedy requires buying into those identities and accepting them as sincere. But Jeselnik’s act requires cognitive dissonance. He cannot be wholly the person he plays onstage or it would all be too horrible to laugh at. And in life offstage, he is different. He is a deliberately, unusually slow speaker when he performs, often pausing for seconds at a time so the audience can sit with the discomfort. In conversational speech, he’s faster, but his words have the same weighty, carefully chosen quality. He is thoughtful, polite, a little particular, and bordering on ascetic in his singular focus on stand-up as an artistic end. “People saw his persona as like, Man, this guy is an asshole,” his friend and podcasting partner, Gregg Rosenthal, says. “But it was harder for me to see because I knew he wasn’t that big of an asshole.” As he’s gotten older, Jeselnik says, tragedy and grief affect him more. “Friends getting cancer … There are things where you’re just waiting for the news from everyone. I’ll be 46 in a couple of months,” he says. “A lot of things don’t make me laugh.”

But that doesn’t mean he’s not still drawn to dark imagery. Flight of the Scholar is not the only art in his apartment. There’s also a photograph by Nadia Lee Cohen, even larger than the Hulin, that hangs in the entryway — a young woman in full-glam hair and makeup sitting at a kitchen table and smoking a cigarette while breastfeeding an infant. There’s a small painting of an upside-down shark submerged in water, the entire image washed in a lurid red. In the corner, off to the side of the Hulin and above Jeselnik’s row of full bookshelves, there’s a small Pulitzer Prize–winning 1975 Stanley Forman photograph printed from the original negative, one that Jeselnik points out to me. “I love this a lot,” he says. The image is of a Boston fire-escape collapse: a woman and child in free fall, seconds before the woman’s death.

“It almost looked like a trampoline at first,” he adds, recalling the first time he saw the image. “And then I was like, Oh no. That’s terrifying.” He was so captivated by it that a friend gave him the print as a gift, and he hung it near the bloody shark, the young mother smoking a cigarette, and the child falling down the stairs, to be seen every day by an audience of him and his dog, a Jindo-Akita mix named Redrum. When I visit, Redrum (who Jeselnik calls Rummy) is not at home. He’s been sent to stay with Jeselnik’s assistant for the day. He’s nervous, Jeselnik explains to me, and does not do well with strangers. He shows me Rummy’s picture on his phone’s lock screen, and I point out that he looks exactly like Jeselnik. “Yeah,” he says. “Everyone says that.”

Jeselnik grew up in Pittsburgh, the eldest in a Catholic family of five children. His mother, Stephanie Jeselnik, says that he was attracted to unusually dark topics from a young age. “Death, dying — he would always ask me questions. Even as a 4-year-old, it was graveyards, what happens when you die. He didn’t understand why people wouldn’t talk about it. And I would try to change the subject.” He loved Bret Easton Ellis, the White Stripes, and “Deep Thoughts” by Jack Handey on Saturday Night Live, and he had a reputation for saying things at school to get his teachers to laugh. “Sitting down with his teachers was not always fun,” his mother tells me. “They would have a list of things they had to complain about. But he was always very funny.” She also suggests that Jeselnik gets some of his dark humor from his father, Tony Jeselnik, a lawyer. (When I later share this with Anthony, he says he may well have gotten his work ethic from his father, but “to credit my dad for my dark sense of humor is bordering on libel.”) As he got a little older, school became a battle for teachers attempting to correct his behavior while also trying not to laugh at it. “I remember the teachers saying they might laugh, but after they finished laughing, they were scared. I think I was just a lot darker than most class clowns,” he says. I ask if they were right that he needed to be disciplined. “Yes and no,” he says. “If you look at what I became, then no, they were wrong. But they didn’t know this was even a possibility.”

After high school, Jeselnik attended Tulane as an English major with an interest in creative writing, where he says his college professors disabused him of the idea that Ellis was a good writer. (“There are better writers out there. Read Donna Tartt.”) But stand-up was never something he considered for himself, and his early-career aspirations were focused on finding a Hollywood TV-writing job. He interned at a small studio before his senior year of college, where he read scripts and took coffee orders. And after graduation, his father connected Jeselnik with his college friend Jimmy Brogan, a longtime writer for Jay Leno. Brogan’s advice — that stand-up would improve Jeselnik’s writing — was the first time he considered performing onstage.

After moving to Los Angeles in 2001, Jeselnik crashed at a friend’s place, worked at Borders until he could find an industry job, and watched comedians like Silverman and Andy Kindler at open mics. Borders stocked a book called Step-by-Step to Stand-Up Comedy, by Greg Dean, which Jeselnik read (“I believe I stole it,” he says, ironic given that his job at Borders was loss prevention), and he discovered that Dean taught classes in Santa Monica. He took the class twice, built a ten-minute set that killed at the class’s final performance, then had a panic attack at an Ice House open mic in March 2002, where he rushed through seven minutes of material in three minutes flat. He spent the next several months standing outside of open mics and not actually going inside, until he went to see Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedian documentary on opening night and realized he needed to keep bombing in order to get better: “I immediately was like, Go get the bad out of you. Do as many bad sets as you can get, get them closer to good, and never look back.”

In those early months, Jeselnik says, the cocky bravado that eventually became his trademark was the result of nerves. “If the joke didn’t work and I said something very egotistical, it brought them back,” he says. “But the deadpan was, I’m terrified. I’m nervous. I only have these jokes. I’m not telling a story. I’m living and dying on these words.” In the meantime, he’d been fired from his job at Borders, but his business minor from Tulane allowed him to work as an accountant for the shows American Dream and Deadwood. “I was able to have these jobs that let me out at 6 p.m. to go to open mics,” he says. “And when they ended, I had six months of unemployment, and having that was huge.”

By 2009, his comedy career was taking shape. His half-hour debut comedy special for Comedy Central Presents premiered in January, and he joined the inaugural writing staff of Late Night With Jimmy Fallon. The moment his comedic voice really clicked, he says, is when he wrote a joke he’s talked about repeatedly in interviews. “My girlfriend likes to joke she’s got a chocolate addiction,” the line goes. “So I put her in the car and I drove her downtown, and I pointed out a crack addict. And I said, ‘See that, honey? Why can’t you be that skinny?’” He taped it for the Comedy Central Presents special, and while the crowd hollers in shock when the punch line arrives, Jeselnik pulls what will become a characteristic expression throughout his career: a shit-eating grin. Jeselnik describes this as “a mean, smart joke you couldn’t see coming.” He was not making a conscious choice to try a specific personality onstage or carefully craft an identity; instead, it was his discovery that the unexpected punch lines he liked best required him to become a certain kind of narrator — to be, as he puts it, “effortlessly cruel for no reason.”

The joke is so pivotal for him that he retells it in Bones and All as part of the special’s closing retrospective on the last 20 years of his work, and it gets as much reaction from his 2024 crowd as it did over a decade ago. The end of the joke is designed to outrage an audience, and it does that job well. But the reveal of it, the twist, is not that the girlfriend in that joke is annoying or that cocaine addicts are idiots. It’s that the teller of the joke is a jerk, even more of a jerk than the setup initially suggests. Offensiveness is often so predictable, following along rote, well-worn pathways of racism, sexism, homophobia, and other fears. Jeselnik’s art is in finding ways to be such an astonishing asshole that the nature of the insult is legitimately surprising. His punch lines are cartographic: His material lives along the lurking boundaries of cultural taboos, and the act of crossing them makes those lines brightly visible. Comedian Nikki Glaser, who started in the L.A. comedy scene not long after Jeselnik, was drawn to his work because of its similarity to her own sensibility. “My favorite game to play when I watch his specials is, after the setup, to try to predict the punch line. I never can,” she says. “So many of us feel pressure to reinvent ourselves, or to get more honest, or reveal more about ourselves. He’s kept it … You know, you can’t pin down what he’s about.”

Glaser recalls seeing Jeselnik perform at an open mic early in his career, long before any crowd could arrive knowing what to expect from him. “He had his notes up there with him, and he said, ‘I don’t have these notes because I don’t know my jokes. I brought these notes onstage because I don’t respect any of you.’ That was a formative moment for me,” Glaser says, “to witness someone be that bold and aggressive onstage and have it work.” When I ask him about that line, Jeselnik is both pleased and annoyed: “That’s one of my favorite jokes. I always do it when I’m trying out jokes, and then in the fucking Showtime documentary about the Comedy Store that Mike Binder fucked up, he used that without my permission. He put it in there. And listen, no one saw that thing, so I can still do it.”

He is brutally honest in his assessment of the state of stand-up comedy as he sees it: “I would guess that most of my comic friends think I’m a better comic — that I’m more pure, that I do things they would not try to do.” He is annoyed by the current wave of indie-scene clowning comedians: “It’s influencers who decided stand-up was going to be too hard.” Bringing a guitar onstage, he says, is like bringing out a ventriloquist’s dummy, a way to make the comedy easier. “One of my gifts is that I’ve never tried to make it easier. I’ve always kept it hard,” he says. “If I show up and do a silly dance? I couldn’t operate like that. Too much pride.” On the topic of Matt Rife, a comedian with a growing popularity and a reputation for being offensive: “I truly believe all roads lead to me. I just don’t know why you could eat steak and you would want to eat cow shit.” Does it bother him that audiences are so drawn to Rife’s work? “I’m sure Gordon Ramsay doesn’t lose sleep at night because McDonald’s sells billions of hamburgers. I also take exception to the idea that the country prefers Matt Rife over me. That’s like saying the country prefers James Patterson over Sally Rooney. Popularity is not a metric I use to measure myself against other artists.”

When I meet him again in late October, he is gleeful at the prospect that the Madison Square Garden Trump rally, where Tony Hinchcliffe joked about Puerto Rico being a “floating island of garbage,” might be the end of Hinchcliffe’s career: “He thought the Brady roast was his big moment, even though I think those jokes were hack as hell.” When I ask him later how he’s thinking about comedy after Trump’s election win, he says that his job “is the same whether it’s raining or shining. Everything is an opportunity.” His opinion of Hinchcliffe remains unchanged: “He is a troll, basking in the shadow of Joe Rogan.” He has no patience for displays of vulnerability or intimate disclosure, either — the Edinburgh-style one-person show that reveals a traumatic backstory. “There’s no comedian who tells me what their life is like where I give even the slightest semblance of a fuck. I do not care. You’re wasting time. I get that there are people who are interested in this, but it’s not what I want to do. I have an hour up there; I want to pack that hour in with pure ingenuity and brilliance,” he says.

For a short period in 2014, Jeselnik was developing a show for FX that would have been more personal. He had left his short-lived Comedy Central late-night show, The Jeselnik Offensive, the year before, and he was “sick of talking about the news every week.” The FX series, which he describes as “a bisexual Louie,” would allow him to switch gears — flesh out a narrative, explore multiple characters, “spend a year shooting it, and then put it out there.” But he didn’t get very far into the process, he says, before changing his mind. He gave back the money he’d gotten for the deal, even after the network offered to let him write the script without starring in it himself: “I said, ‘You know what? I don’t even want to work on this anymore. I don’t want to do a narrative, I don’t want to talk about sexuality. It doesn’t really benefit my comedy.’ Writing the story, writing all the characters, it was like, This is too much.” I ask about the idea of a “bisexual Louie” and if the protagonist was based on him or a character he created. “A little of both,” he says. “It would’ve been someone figuring out their sexuality later.” Was that an experience he had? “Sure,” he says. “Yeah.” I note the bookshelves that line his wall, which include works by Philip Larkin, Raymond Chandler, and Jonathan Franzen, as well as Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life and Jeremy Atherton Lin’s social history Gay Bar. But he didn’t want that to be part of his comedic identity? “I didn’t really have a comedic angle on it,” he says. “It was like, Oh, maybe I’m gonna try this out. Then I was like, No, I don’t really have anything to say about it, so maybe it’s someone else’s story to tell. Or just … Yeah, it never really came together, and no one really gave a shit.”

During my first visit with Jeselnik in September, he’s in between two legs of an international tour. His apartment has been carefully cleaned, but there are some items that don’t belong to him. He recently broke up with his long-term girlfriend, a photographer who works at the Comedy Store, and he’s hoping she can come pick them up while he’s in Europe. His fridge is nearly empty; there’s a Trader Joe’s salad he bought that day, distilled water, and some condiments he says were also left by his ex. He’s spent years recording a chatty podcast with Rosenthal, but he says he’d like to end that podcast soon: “I’m just over mixing podcasts with stand-up.” I ask him about other hobbies or interests. He cites his dog and also that he reads dozens of books a year. We discuss Lev Grossman’s Bright Sword, which he loves. He asks me for my top-ten books of the year; he recommends I try Kevin Barry’s The Heart in Winter. But he says the books are in service of the comedy. “I really, really love comedy. I think I understand it in a way I don’t understand other things.”

Bones and All opens with seven minutes of material about gender, trans people, and the recent anti-trans obsessions of comedians like Dave Chappelle. Part of the gambit comes from Jeselnik’s framing. He tells the crowd that he’s about to tell them a joke that used to be his closer until a woman informed him it was too offensive and could upset trans people in ways he might not intend. In the special, he tells the joke anyway, now as the opener. It’s a series of lines comparing trans people to pregnant women, and then he offers the twist: “I love trans people. You know what I hate? Pregnant women.” As stand-up, it accomplishes a challenging rhetorical maneuver, positioning Jeselnik as the badass rule-breaker who tells a joke that crosses a line and then swerves by finding an even bigger line to cross. When Jeselnik tells me the story in person, it is earnest to a fault. He talks about the trans woman who really did come up to him after a show to say the joke might bother trans audience members, and how by the next night, he had reworked the material in response to her critique. The experience of the story is different as Jeselnik explains it to me sincerely rather than as an onstage jackass. When he tells it to me this time, it’s not a story about breaking rules. It’s a story about receiving feedback and adjusting to make the material better, about being curious and remaining open to change. But onstage or off, the takeaway is identical: Jeselnik is immensely proud of his work. It is still an upsetting joke, but now he’s sure that it’s offensive in a way he truly intends it to be.

But intent can be ambiguous. When I ask him about the number of photos in his apartment that depict children in uneasy or perilous positions, Jeselnik is surprised. “It’s not like I went into a store and bought all of those at once,” he says, pointing out that he has several pieces that are a completely different tone (including a painting of his dog). Surely, I offer, the fact that these images have all ended up here together without him realizing it is just as suggestive as if he’d gotten them all deliberately as a set? He starts to tell me more specifically about the Stanley Forman fire-escape photo and why he’s so drawn to it. “It looks like everything’s going to be okay, and it’s not,” he says. “It’s like a punch. It’s not an aw; it’s like a fuck.” It’s not that the darkness is more real, he says, but he does think it’s “less of a sellout. Everyone else is like, We gotta have a happy ending. I don’t think it’s unfair or untruthful. I just think it’s boring.”