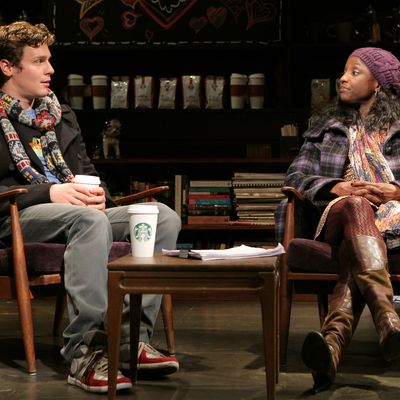

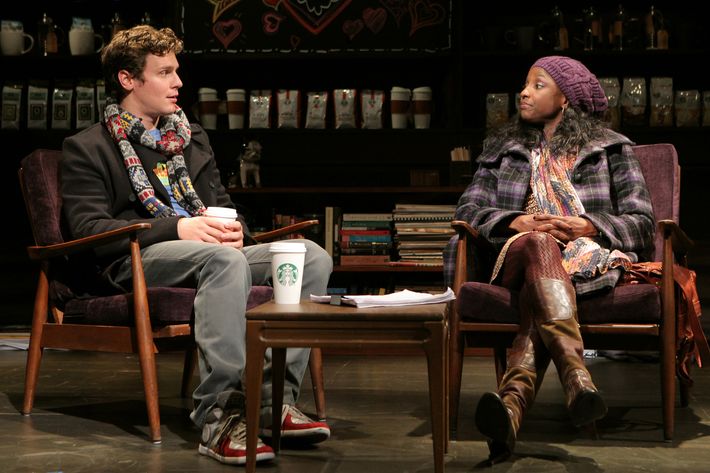

Jeff Talbott is a longtime actor, first-time playwright, and in his debut work, The Submission, he displays an actorÔÇÖs homing instinct for the Moment of Heat and the eminently deliverable line. He also has a quartet of lusty young talents: Spring AwakeningÔÇÖs Jonathan Groff, True BloodÔÇÖs Rutina Wesley, Eddie Kaye Thomas of American Pie fame (hugely fun onstage, and not onstage nearly enough, here or elsewhere), and Off BroadwayÔÇÖs newest hipster institution, that tall drink of silken tofu Will Rogers. They deliver TalbottÔÇÖs punchy, pseudo-Millennial dudespeak with gusto and edge. Every word comes pre-weaponized, and director Walter BobbieÔÇÖs scene work sings. ItÔÇÖs all highly watchable, even when itÔÇÖs vaguely ludicrous ÔÇö which is, IÔÇÖm sorry to say, most of the time. Because all TalbottÔÇÖs missing, really, is a play.

Which isnÔÇÖt to say he doesnÔÇÖt have a situation. Oh, heÔÇÖs got a doozy: What if, in a J.T. Leroy twist, the author of a hit Precious-esque play turned out to be a gay, middle-class white dude, Danny (Groff)? What if he hired a struggling black actress, Emilie (Wesley), to play his public persona, in order to get his play accepted in the Humana Festival? (With all due respect to Humana, portraying it as the gleaming gateway to instant wealth and fame is the playÔÇÖs best, most absurd, and probably least intentional gag.) So: Is Danny a revolutionary fighting for a post-racial society, or a reactionary sabotaging the inner workings of Affirmative Action? WhereÔÇÖs the line between artistic license and rank exploitation? And who says a suburban Caucasian canÔÇÖt write about the projects, anyway? Who owns a story?

If youÔÇÖre looking to enjoy The Submission, donÔÇÖt expect interesting answers to these questions. It begins playfully and cleverly enough, coyly withholding key bits of information (what DannyÔÇÖs written, for example, and how he plans to promote it) and teasing us with lots of underslung white-boy Ebonics (ÔÇ£Yo, muthafuckah,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£Hey, bitchÔÇØ), which gather ironic steam as the night wears on. But this is a play that delights itself primarily with dazzlingly un-PC fireworks and reckless know-nothing generalizations ÔÇö which is why, in the spirit of the thing, IÔÇÖll indulge in a few myself. What white American writers of a certain age seem to mean by An Incendiary Story About Race (and I base this, with all due superficiality, on a sample that includes only The Submission, David MametÔÇÖs score-settling Race, and Crash, Paul HaggisÔÇÖs crowning work of well-intentioned Oscar-clip ventriloquism) is a story where the characters say ÔÇ£what they really meanÔÇØ and/or ÔÇ£what weÔÇÖre all thinking.ÔÇØ Characters vent their deepest and most hurtful assumptions about each other, tit for tat, in tidy little domino lines: There are no angels! (Except when there are.) All prejudice is distributed justly among the races (or, more accurate, the types) and carefully, mathematically paralleled to cancel out any creeping victimology. (Unless itÔÇÖs dramatically necessary, in which case: open season!) Everybody gets a turn in the dunking booth.

The words are the star, those mystic, unspeakable words were all supposed to be dying to hear, for the sheer Tourettic release. Its the same logic that drives lazy stand-up comedy: Of course political correctness has driven the real debate over Difference in America underground, and only a cathartic wordletting can correct the repression. The chief word in question, as always, is nigger, and the lead-up to its detonation is so titillatingly predictable that its more or less pornographic. (Which is, interestingly, the word that Emilie uses to describe Dannys play  just twenty minutes after praising it to the high heavens. Huh.) In The Submission, we get two squirts for the price of one: Emilie hits Danny with faggot, authorizing him to release the nigger hes been damming up, none too subtly, for the past 90 minutes. Note: This is not a spoiler. Indeed, were tapping our feet, waiting for it, all night long. What does this say about us? And who, by the way, are we?

ÔÇ£WeÔÇØ seem to be the presumed mostly white, probably middle-aged audience for this play, and ÔÇ£weÔÇØ gasp ÔÇö reflexively, reverently, relieved ÔÇö as the Great and Powerful Epithet is finally, inevitably uttered. The billboards have appeared for miles, and finally, there it is! Huzzah? At the same time, we thrill and shudder as Emilie burns down her masterÔÇÖs house: Danny, long before he lets loose his N-bomb, is shown to possess racial blind spots roughly the size of the Confederate White House. Groff connects with DannyÔÇÖs untutored entitlement and the childish innocence of his ambition; this is, after all, a guy who blithely makes the remarkable decision to advance his career via an elaborate, racially charged literary deception. But who does that? Groff doesnÔÇÖt have an answer, and neither does Talbott, and this is a problem: Danny, for all his muted fury, is a blank and a bore. As for his partner turned nemesis, Talbott tries halfheartedly to humanize Emilie beyond her Go-tile dialectic with Danny. But who, really, is she? Wesley is sexy and fearless onstage, but we learn almost nothing about her character, except that sheÔÇÖs black, female, and sexually forthright. (Talbott lingers overlong on a phone-sex scene Emilie shares with RogersÔÇÖs character, Trevor, whoÔÇÖs mostly a stammery bystander, a Jiminy Cricket.)

Overall, Emilie comes off pretty middle-class and buppified, yet she assumes instant and never-questioned authority over all matters touching Black Poverty. And nobody asks her what ghetto she grew up in? For that matter, how does a reckless, ruthless, insensitive shit like Danny crawl out of his own puckered art-hole long enough to compose an emotionally compelling play, inside or outside of his life experience ÔÇö a play that everyone agrees is genius? (When we hear it read aloud, in mercifully brief snatches, DannyÔÇÖs play sounds about as ÔÇ£authenticÔÇØ as West Side Story.) Can it be that his own sense of grievance, as a gay man and frustrated artist, is so massive yet so nebulous that heÔÇÖs grafted it onto Blackness, the white AmericanÔÇÖs touchstone of ultimate disgruntlement? The play, like many of its ilk, is far too delicately symmetrical to answer questions that messy, and Danny and Emilie, as gladiators, are a tedious pair, all brute overhead smashes, no deft sword work. The Submission is more of a game than a debate, but itÔÇÖs a simpletonÔÇÖs game, a Rochambeau of letÔÇÖs-get-real one-downsmanship. LetÔÇÖs not get ÔÇ£real,ÔÇØ shall we? LetÔÇÖs try to get somewhat interesting. Conflict is no guarantee of drama, spotlit Actor Moments donÔÇÖt add up to cogent playwriting, and radioactive words (even The Word) are no merit badge of bravery or honesty: For all their flash, they canÔÇÖt, in an instant, rescue a story from its own contrivances or a character from the box his authorÔÇÖs put him in. In short: LetÔÇÖs write another play. This oneÔÇÖs getting kinda tiresome.

Lemon Sky

Keith Nobbs, most recently seen/wasted in the dismissable Lombardi, is reason enough to catch the Keen CompanyÔÇÖs serviceable revival of Lemon Sky, the sunkissed, snakebit 1970 memory-play by Lanford Wilson. He plays Alan, a thirtysomething writer trying to narrate, correct, and annotate his memories of being 17 in 1957, a naif reuniting disastrously with his morally emancipated boor of a father, Doug (Kevin Kilner), in the treacherous dreamscape of late-fifties SoCal. Alan announces, at the beginning, that heÔÇÖs going to do two things: (1) try to make an honest story out of his lifeÔÇÖs formative catastrophe (one where heÔÇÖs ÔÇ£as a big a bastardÔÇØ as everyone else) and (2) fail. Nobbs, shifting fluidly and thrillingly between two personae ÔÇö blank-page naif and anxious thirtysomething marginalia scribbler ÔÇö never grinds his gears or breaks a sweat. Just our hearts.

WilsonÔÇÖs play unfolds with Chekhovian languor, an endless summer that Alan seems to be prolonging with his asides, asterisks, and disclaimers: He spoils his own story more than once, gives away the game, often defuses the suspense with a premature revelation. Part of Alan desperately wants his father not to be villain of the piece, even though Doug is and must be a monster; his inevitable rejection of the son heÔÇÖs already abandoned once is both the end of AlanÔÇÖs childhood and the foundational event of his writing life. But Alan/Wilson is in no hurry to get there, and neither is director Jonathan Silverstein, who ushers the first act along so loosely and gently that patience starts to look suspiciously like flatness. HeÔÇÖs betting mostly on Nobbs to carry us. ItÔÇÖs a pretty good bet.

The summer begins in golden promise, even though clouds are clearly visible on the horizon: Alan travels by Greyhound to San Diego to live with Doug, who left him and his mother for a life out West that has fewer restrictions on his rambling, rapacious spirit. (He also left something else back East, a tragedy with no name, the details of which donÔÇÖt surface until late in the second act.) Now DougÔÇÖs got a new wife, the preternaturally indulgent Ronnie (a superb Kellie Overbey, playing brilliantly in the terrifying gray space between dreamy Cali Zenlightenment and Stepford stupor); heÔÇÖs also got two new biological sons and two epically screwed-up foster daughters (Alyssa May Gold and Amie Tedesco). Doug is the crude evolution of a covered-wagon patriarch; heÔÇÖs a small man who likes having a big tribe of devotees around him and enjoys his privileges, especially the sexual ones. HeÔÇÖs an old-fashioned pervert whoÔÇÖs convinced himself heÔÇÖs a grand paterfamilias; Kilner would be a bit more convincing, a bit more terrifying, if he were just a hair better prepared. (He had some stumbles the night I attended.) ItÔÇÖs a performance, I suspect, that will deepen over time. Nobbs, however, is already at peak ripeness, which is fortunate, because heÔÇÖs the play: his confessions, his retractions and qualifications, his limitations. He opens with a deceptively simple question ÔÇö ÔÇ£How can I write about Dad?ÔÇØ ÔÇö and proceeds to show us just how complicated and unanswerable that question is. Nobbs is so insistently alive onstage (on at least three levels of meaning, in two timelines, at any given moment), he seems to be composing WilsonÔÇÖs colloquial poetry in his own mouth, in real time. He rules the stage with such ease, itÔÇÖs genuinely distressing when he loses control of it, and finds himself, despite all his attempts at writerly evasion, at the mercy of his own story.

THE SUBMISSION is playing through October 22 at the Lucille Lortel Theater.

LEMON SKY is playing through October 22 at the Clurman Theatre.