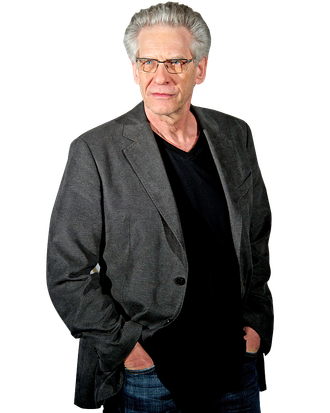

Some critics have called David CronenbergÔÇÖs latest, A Dangerous Method ÔÇö based on contentious letters between Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) and Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortenson) over the treatment of a beautiful, brilliant, and sexually repressed Russian, Sabina Spierlrein (Keira Knightley) ÔÇö a departure from his usual body horror, the Canadian master going thoughtful and introspective at 68. And well it might be, if there hadnÔÇÖt been such deep psychological underpinnings to Jeff GoldblumÔÇÖs transformation in The Fly or Jeremy Irons losing his mind as twin gynecologists in Dead Ringers (which, if youÔÇÖve forgotten, Charlize Theron LOOOOOVES). What could be more Cronenbergian than two handsome men who kind of look like each other fighting over philosophies about bodily urges and a fascinating woman neither of them quite understands? ItÔÇÖs like a naked Russian bathhouse fight of minds! Cronenberg spoke to us about talk therapy, his love of Robert Pattinson, the History of Violence sequel, and why calling things Cronenbergian is hooey.

I was thinking that maybe we should just start off like you start off A Dangerous Method with Carl Jung and Sabina, and you could just tell me things. Do some talk therapy.

[Laughs.] But I donÔÇÖt need therapy, do you? Maybe you should be the one whoÔÇÖs talking. IÔÇÖm happy to listen.

No, IÔÇÖd like to know whatÔÇÖs on your mind.

WhatÔÇÖs on my mind is just doing a lot of interviews. IÔÇÖm afraid my mind is not clear at the moment.

Are interviews actually kind of difficult? Do you find yourself circling back on yourself constantly?

Well, itÔÇÖs sort of physically demanding, you know? IÔÇÖve been traveling a lot. And IÔÇÖve been with the film at six film festivals in six different cities, and a lot of airplanes, a lot of flying. ItÔÇÖs not the talking so much that is difficult, actually. There are always interesting things that are happening and youÔÇÖre meeting interesting people. ItÔÇÖs the organization and the travel that is the problem.

Could you come up with a Cronenbergian movie about the disintegration of your body through this process?

ThatÔÇÖs too horrifying. Even for me, thatÔÇÖs too horrifying. Although itÔÇÖs funny that you mention it, because just an hour ago, it occurred to me that you could do at least a play, if not a movie, where you have one guy sitting there, and people come in the next chair, one after the other, after the other, to do interviews. I donÔÇÖt know if it would be a horror film or not, but it would be intense.

Would it be horrifying for you in that you donÔÇÖt want to do a movie about your own disintegration?

IÔÇÖm constantly doing a movie about my own disintegration. When people talk to me about The Fly, for example, all those years ago, and they wanted the movie to sort of be a metaphor for AIDS ÔÇö because of course that was a huge topic of that moment ÔÇö I said, ÔÇ£Well, it could be that, but I think itÔÇÖs more like aging.ÔÇØ Which we will all undergo and have to deal with. So, certainly when I did The Fly I was thinking of my own disintegration.

But that was a while ago. You were thinking about your disintegration in 1986?

I know, but you know, I anticipated it, and everything I thought was going to happen, is happening. Body parts are falling off, all of that stuff.

[Laughs.] You donÔÇÖt actually have body parts falling off, do you?

Maybe we can discuss it over a drink, you know?

YouÔÇÖve always been interested in the psychological. Has that interest increased for some reason?

No, IÔÇÖm still the same person. ItÔÇÖs kind of interesting┬áÔÇö a friend of mine pointed out that my very first film, which IÔÇÖd totally forgotten about, was a seven-minute short called Transfer, and it was about a psychiatrist and a patient. And the patient was kind of stalking this psychiatrist because that turned out to be the only relationship he ever had that meant anything to him. And so, making A Dangerous Method, in a weird way, is coming full circle. That was before I did horror films and sci-fi films and so on. IÔÇÖve always been interested in that unique, invented relationship. Freud invented a new human relationship, which is the relationship between an analyst and his patient. Which has seeped into popular culture, to the extent that you often find youÔÇÖre having sessions with your friends that are like an analyst and a patient. But it never existed before Freud. The closest you would come is a priest in a confessional. But in fact, the priest is of course being very judgmental, and youÔÇÖre confessing a sin. In analysis, the analyst is supposed to be completely neutral and nonjudgmental. ItÔÇÖs really a kind of unique relationship that has a great fascination for me.

So before Freud, did people just not talk about their feelings?

Well, no, they didnÔÇÖt talk that way about their feelings. In fact, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in other words Central Europe, you would never find men like Jung and Freud, professional men of stature and respect, talking about bodily fluids, body parts, orifices, erotic dreams, fantasies, erotic fantasies. Men, they would never talk about that. It was absolutely taboo. And of course when you throw Sabina [Keira KnightleyÔÇÖs character] in the mix, and now you have a woman who is absolutely their intellectual equal and is talking about the same things from a womanÔÇÖs point of view ÔÇö her erotic fantasies, her bodily fluids ÔÇö it was, in a sense, they were inventing modernity. They were inventing that way of speaking. Now, every blog, every Dr. Phil show, people are talking about this kind of stuff. People did not talk about that stuff before Freud. They simply didnÔÇÖt.

Do you think you couldÔÇÖve done a film about different psychoanalysts? Or is it their obsession with the body that creates a through line to what you were doing with horror films?

Well, you go to the source. I mean, Freud was the first. Freud invented psychoanalysis. So, naturally, as a dramatist, you want to get to the most primordial moment. And this is it.

A lot of critics, though, have talked about how this isnÔÇÖt necessarily a natural through line for your career. That A Dangerous Method doesnÔÇÖt seem as natural a progression from even Eastern Promises.

ThatÔÇÖs totally, totally irrelevant. See, this is very common. IÔÇÖm often telling critics that they should not confuse their process with mine. I donÔÇÖt care what movies IÔÇÖve made before. I donÔÇÖt care what people think is Cronenbergian or not. ItÔÇÖs irrelevant to me. ItÔÇÖs as though IÔÇÖd never made another movie when IÔÇÖm making this movie. ThereÔÇÖs nothing that I can take from those other movies, or what people think that I do, that is creatively of use to me. When IÔÇÖm making this movie, once IÔÇÖve decided that yeah, this is a subject that interests me, IÔÇÖm going to make this movie, I just focus on it. ItÔÇÖs of the moment. The movie tells me what it wants. I listen to the movie; it tells me what it wants in terms of style, visual style, dramatic style. And I have no desire to impose some preconceived idea of Cronenbergness on the project. The movie grows organically out of itself rather than having me impose some sort of pattern or template on it. So, to me, all talk about natural progression from one movie to another is completely irrelevant. And the other thing is, too, what is amusing to me is what is assumed, even if itÔÇÖs not exactly expressed by these people who write this stuff, is that I have total control over what I do, and when. ItÔÇÖs like, ÔÇ£Oh no, I think at this point of my career I shall do a biopic. Because I have not done that before, and I need to show that I can do that.ÔÇØ They probably think thatÔÇÖs exactly how it goes. Well, not really. ItÔÇÖs like, this movie is the one that got financed, so thatÔÇÖs why IÔÇÖm doing it now. I might have done it ten years ago ÔÇö which is actually when I approached [playwright] Christopher Hampton to do it. But we couldnÔÇÖt get the financing. Christopher thought maybe he wanted to direct it. I wouldÔÇÖve done it ten years ago, if all of that had come together. You see? So all talk about natural progression is kind of a laugh for me. Because it has nothing to do with the reality of moviemaking. And particularly, movie financing.

Are you more able than others to jump from subject to subject because of who you are? At this point, does your reputation allow you to do whatever you want to do?

No, itÔÇÖs the reality of filmmaking. Look, I talked about it with Marty Scorsese, because people think that Marty can do anything he wants. Because heÔÇÖs Marty, right? He canÔÇÖt! HeÔÇÖs got projects that he canÔÇÖt get off the ground, because people think they wonÔÇÖt make enough money, or theyÔÇÖre too expensive, or any of those things. So, maybe Spielberg can do almost anything he wants ÔÇö although I did hear he had trouble getting SchindlerÔÇÖs List actually made ÔÇö [but] money talks. WeÔÇÖre all completely vulnerable to the financial environment. I think of moviemakers as being like amphibians. WeÔÇÖre like the frogs with the thin skins. WeÔÇÖre the first ones to react, to have an allergic reaction to the toxicity of the air. When the financial meltdown came, it really affected what movies you could make. Sources of financing dried up, sources of distribution folded. Warner Independent disappeared. Places that you used to go to be able to pre-sell your film, suddenly you couldnÔÇÖt pre-sell your film. And that meant that only the most blatantly commercial, repetitive movies like sequels and remakes and stuff could get made. So all of those things, when people are being theoretical and analytical about why you made this movie now, they ignore all that stuff. And theyÔÇÖre ignoring the actual reality of moviemaking, thatÔÇÖs what I mean.

You speaking about the financing of movies made me wonder if thereÔÇÖs a Cronenberg movie to be made about Occupy Wall Street or the current economic climate. Is that the new horror?

ThereÔÇÖs enough horror in the world. The old horror is quite good, you know? No, actually, I have great empathy for the Occupy Wall Street movement. It doesnÔÇÖt seem like the subject of a movie for me, but the anger that people have at the incredible excess of the financiers and so on, and the arrogance of them, and the entitlement of them ÔÇö I have great empathy for that. Most people, now that theyÔÇÖre realizing some of the things that have gone on, are outraged. And IÔÇÖm one of them. You know, itÔÇÖs funny: IÔÇÖm not actually looking for movies. ThatÔÇÖs the funny thing.

[Laughs.] I know, IÔÇÖm not trying to suggest them for you.

But itÔÇÖs sort of a meditative thing. You have to be very open and calm, and not desperate, and eventually a movie will come to you. ThatÔÇÖs the way it feels to me. And it can come from anyplace. When I heard about Christopher HamptonÔÇÖs play, I was really just reading it because Ralph Fiennes was in it, and I had worked with [Fiennes] on Spider, and I was interested to know what he was doing. I wasnÔÇÖt really looking for a movie, it kind of just surprised me when I read the play, that I suddenly got excited about it as a movie. Likewise, Cosmopolis, which IÔÇÖve just done, the producer appeared ÔÇö heÔÇÖs a Portuguese producer named Paulo Branco ÔÇö and he appeared and he said, ÔÇ£IÔÇÖve got the rights to this Don DeLillo book, and I think you might want to make it into a movie.ÔÇØ And I phoned him back two days later, and I said, ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖre right, I do.ÔÇØ But it was solely by surprise. So thatÔÇÖs really, in a way, how movies come to you. They can come from anyplace. But it doesnÔÇÖt really have anything to do with the continuity, or the arc of your career, or any of that stuff. I come back to that. IÔÇÖm just trying to give you from the inside out the way it feels to me.

YouÔÇÖve finished shooting Cosmopolis, which you wrote, based on the Don DeLillo novel about a 28 year-old billionaireÔÇÖs one-day odyssey across Manhattan. What was it about it that made you think, Okay, this is the next film IÔÇÖm going to make?

I really have no idea other than I thought the dialogue was absolutely incredible. Don DeLillo, whose work I had known before, but I didnÔÇÖt know that book, he has a tone, thereÔÇÖs a special kind of dialogue he has thatÔÇÖs really ÔÇö itÔÇÖs like when you see a Harold Pinter play and people talk about Pinteresque dialogue. ItÔÇÖs studied. ItÔÇÖs stylized. But somehow itÔÇÖs also incredibly real. ItÔÇÖs interesting, because you know when you write a script ÔÇö I did write the screenplay for it as well, based on the novel ÔÇö and when you write a screenplay, itÔÇÖs odd, the only stuff that you write that actually gets directly onto the screen is the dialogue. All of your descriptions and so on, which in a novel you worry about the literary style and your metaphors and all that, but in a screenplay thatÔÇÖs all irrelevant. ThatÔÇÖs just very mundane and pragmatic. But the thing that really ends up exactly the same way onscreen is the dialogue. So as I say, it was really the dialogue, and the way it was delivering in Cosmopolis that made me think this should be a movie.

Because of the dialogue, you were able to write the screenplay in six days, something like that?

ThatÔÇÖs correct. YouÔÇÖve heard that story.

Were you just wholesale transferring dialogue, and rearranging?

I thought, Okay, is this really a movie or not? LetÔÇÖs try an experiment. IÔÇÖd never done this before: I literally went over every page in the book and transcribed the dialogue and put it into movie form. With dialogue, but with no description, no scene headings or anything like that, using a screenwriting program. And so after three days I had transcribed all the dialogue. And I started to just read it, and I thought, ItÔÇÖs starting to feel like a movie. And then the next three days I filled in all of the screen descriptions, and everything else that would make it understandable to people who are making the movie, namely actors and crew. And there was a script after six days. So that was a unique experience for me. Normally, screenwriting is difficult, especially if youÔÇÖre writing an original screenplay. So you donÔÇÖt expect it to work that easily. But there it was. As I say, you donÔÇÖt want to be predictable. You donÔÇÖt want to know what the arc of your career is, and where it will inevitably lead you. You want to be surprised. I donÔÇÖt want to be bored. I donÔÇÖt want to be predictable, even to myself. Because when you make a movie, youÔÇÖre pretty much devoting two years of your life: to getting the financing together, then making the movie, then promoting the movie. At the very least, itÔÇÖs two years of your life. So you better want to really do it. ItÔÇÖs got to constantly surprise you, and entertain you, and amuse you, and challenge you. Otherwise, itÔÇÖs not a good idea to do it.

Was there anything in particular about the story that appealed to you? ItÔÇÖs about a billionaire who loses his pride and all his money in the same day.

Sure. Yeah, itÔÇÖs incredibly predictive. Not that I care about that. People have often said that my movie Videodrome, for example, was a prophetic movie about the Internet, about interactive media and stuff. But you donÔÇÖt make it because of that. However, itÔÇÖs inevitable when you look at Cosmopolis and realize that Don wrote it in 1999 and how incredibly relevant it is right now in terms of this financial meltdown that weÔÇÖve been talking about. ItÔÇÖs perfect. ItÔÇÖs like, Wow, it just feels right. Though it was written to be set in the year 2000, it doesnÔÇÖt feel like a movie thatÔÇÖs ten years old. It feels like itÔÇÖs right now.

And do you have it set in the year 2000, or did you bring it up to now?

ItÔÇÖs set now.

What was it about Robert Pattinson that made you think he was the right guy for the lead?

HeÔÇÖs the right age. He looks right. He looks good in a suit. He looks like he could be a young, tough, billionaire. And IÔÇÖve actually thought he was quite a good actor who was very underrated in a similar way to Keira Knightley, I think, when I was thinking of her for Dangerous Method. Both of them have had great financial success and are stars based on franchises, but of course to do that you have to have a kind of screen charisma, you have to have a presence, which you canÔÇÖt buy or create; you either have it or you donÔÇÖt. That doesnÔÇÖt mean youÔÇÖre necessarily a good actor, though. But you have at least that. I looked at all the stuff that heÔÇÖs done, and I thought heÔÇÖs a really good actor. And then I spoke to him, and thought not only that, but heÔÇÖs a really smart actor. And heÔÇÖs funny, and heÔÇÖs very sweet. ThatÔÇÖs when I tried to convince him to do the movie, which he was a little afraid of, just because I think he doesnÔÇÖt know how good he is, basically. And I think now that heÔÇÖs done the movie, heÔÇÖs starting to understand how good he is. Because heÔÇÖs terrific.

And was he a fan of your work?

He knew my work, yeah. WhatÔÇÖs interesting, too, about Rob is that heÔÇÖs very well educated in terms of movies and movie and foreign films. On the set, he and Juliette Binoche were talking about the most obscure French films and stuff like that together. He really knows his stuff. And yet, as I say, heÔÇÖs a completely down-to-earth, sweet guy. Lovely to work with. And very funny.

Are you going to go see Breaking Dawn?

I think IÔÇÖll wait for the screener.

YouÔÇÖre not going to go with the screaming fans?

Well, I donÔÇÖt feel the need to line up, letÔÇÖs put it that way. And IÔÇÖm sure thereÔÇÖs going to be big lines for it. But, you know, basically I know what Rob can do having worked with him. I donÔÇÖt have to see Twilight now. I certainly looked at the first two, though, when I was thinking about him.

You did?

Oh yeah, sure. And I watched Remember Me, and I watched Little Ashes. Which is maybe a movie you donÔÇÖt know, but he plays a young Salvador Dal├¡ in that movie with a Spanish accent. And I thought that was pretty interesting, very daring of him to do that, and it indicated to me that he was an interesting, serious actor.

And you were impressed with the work in the first two Twilights?

I was impressed with his screen presence and a lot of his stillness, and a lot of other things. But the other movies showed me he had range. He had the range that I wanted.

Regarding Keira, at the beginning of A Dangerous Method, when Sabina is talking about how she got aroused when her father beat her, she does this thing jutting out her jaw that is seriously painful to watch. I read one review that said if youÔÇÖd put it in 3-D, it would have been one of the scariest scenes in movies this year. She came up with that all on her own?

Well, yes and no. The no part is that she and I discussed the nature of SabinaÔÇÖs symptoms, which we know because Jung wrote about them in great detail when she was being admitted to the Burgh├Âlzli. So we knew what her symptoms were, physically. And as well, we looked at photographs of women who were suffering from hysteria, because thereÔÇÖs some great photographs taken by the French psychiatrist Charcot of his patients and thereÔÇÖs actually film footage that we looked at of patients who were suffering from it. So we knew the kind of contortions and deforming, extreme postures and paralysis and stuff that these patients did. And they were all very extreme and made you all very uncomfortable. So we knew to deliver the reality of it, thatÔÇÖs where we had to go. And then Keira said to me, ÔÇ£Should I just do this with my body and not my face so you can cut around it if itÔÇÖs too extreme?ÔÇØ And I said, ÔÇ£No, I think the face and the mouth is exactly where it should be, because you are being asked to speak unspeakable things. For this woman to suggest all of these sexual things about her father, and her masochist, and so on, these are things that you desperately want to confess, but part of you hates having to express them and is afraid to express them. So it would all come out in deformities around your mouth where youÔÇÖre trying to make the words not understandable and so on.ÔÇØ So thatÔÇÖs a collaboration.

Have you sat next to her as sheÔÇÖs seen the performance? And whatÔÇÖs her reaction?

Like many actors, she is kind of on the fence about watching herself, you know? But she knew it was good. She knew it was good, and of course from the audience reaction she knew it was good. Anyway, IÔÇÖm afraid we have to wrap this up.

Okay, but before we go: Would you do 3-D? People have said that deserved its own 3-D moment and I was just curious when you might do it.

It depends on the project. I lived through 3-D in the fifties; in the 1950s I watched lots of 3-D movies. And it was very hot for a while and then it disappeared. And IÔÇÖm not sure that the same thing wonÔÇÖt happen again. So I think for a certain kind of movie it might be an interesting additional element, but for a movie like, letÔÇÖs say Cosmopolis or Dangerous Method, it would not be worth the expense. It is more expensive to shoot in 3-D, and for me itÔÇÖs not the essential thing.┬á

We had a chance to speak with Cronenberg again at the Gotham Awards this week. Herewith, our backstage banter:

In your speech [video below] you said youÔÇÖve tried desperately to sell out, but failed. Yet here you are getting a free hair dryer.

So, what about that? ItÔÇÖs swag. ItÔÇÖs probably a start. YouÔÇÖve got to start small with the sell outs. Getting a free hair dryer, I say, is a good beginning.┬á

YouÔÇÖre getting a career tribute, so how does this swag compare to the swag youÔÇÖve gotten throughout the year?

[Looking at his Gotham Award.] I donÔÇÖt know what this is worth on the free market. IÔÇÖd have to go on eBay before I could be sure.┬á

Did you notice Charlize TheronÔÇÖs shout-out to Dead Ringers? I thought it was a bid to be in one of your movies.

IÔÇÖm hoping thatÔÇÖs what she was doing. She is a terrific actress. I have met her before in Palm Springs at the Palm Springs Film Festival. That was very sweet. All bribery is accepted.┬á

Do you judge people by which of your movies they praise?

Do you mean is there some movie that if they praise, I have no respect for them? No, IÔÇÖm afraid IÔÇÖm a sucker for a compliment. You can tell if itÔÇÖs sincere and I accept all of them.┬á

What happened to The Fly 2? Why isnÔÇÖt it being made?

Talk to Tom Rothman. [EditorÔÇÖs note: Rothman was actually in the room, as another career tribute winner, but we couldnÔÇÖt grab him in time.] HeÔÇÖs the head of Fox. They own the rights. They own the rights.┬á

You had a treatment 

No, I wrote a script. I actually wrote a script which I liked very much and Fox decided not to go along with it.

Are you pissed off about it?

Well, I like my script.

So what happens with it now?

Nothing. Nothing. It floats in that limbo of great scripts that never get made.

There will be an Eastern Promises 2, though.*

Well, nothingÔÇÖs for sure. It all depends on the economics of the world, for example. If things go worse, then maybe not, because weÔÇÖre very susceptible to that. In indie filmmaking, youÔÇÖre very susceptible to whatÔÇÖs happening economically in the world. But Focus likes it, I like it, Viggo likes it, so weÔÇÖre looking good.

What happens in it?

I wouldnÔÇÖt want to spoil it. Also, itÔÇÖs still quite a way a way from making it and things can change when youÔÇÖre making a movie. ItÔÇÖs a little too soon to say, other than that Viggo would be playing the same character, Nikolai.┬á

Why did you want to do another one?

You know, itÔÇÖs the first time IÔÇÖve ever felt that a movie I did could use a sequel, and itÔÇÖs because I wasnÔÇÖt finished with Nikolai. I wanted to see more of him. ThatÔÇÖs why.┬á

*This post was corrected to show that Eastern Promises 2 ÔÇö not History of Violence 2 ÔÇö is up for discussion.