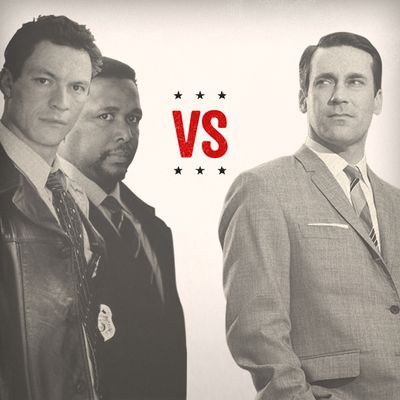

Welcome to the semifinals of VultureÔÇÖs┬áultimate Drama Derby to determine the greatest TV drama of the past 25 years. Each day a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until┬áNew York┬áMagazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 23. TodayÔÇÖs battle: Writer Chris Norris ┬ájudges┬áMad Men┬áversus┬áThe Wire.┬áMake sure to head┬áover to Facebook to vote in our Readers Bracket, where Vulture fansÔÇÖ votes have already diverged from our judgesÔÇÖ. We also invite tweeted opinions with the #dramaderby hashtag.

This boutÔÇÖs heavyweights couldnÔÇÖt seem more different. Mad Men is clearly the boxer of the two: full of style and flash, gorgeous sets and sweeping camerawork, its script throwing epochal-ironic race/sex/alcohol combinations every minute. That makes The Wire our brawler of the old-school: stalking the corners, playing procedural rope-a-dope for several episodes, setting up the body blow that ends it in round five. A strong critical consensus has The Wire by a knockout, with tonier scribes blurbing ÔÇ£novelisticÔÇØ and ÔÇ£literaryÔÇØ in tones eerily reminiscent of the final seasonÔÇÖs Pulitzer-hungry newspaper editor James Whiting: Sending his staff after ÔÇ£the Dickensian aspect,ÔÇØ Whiting courted a media consumer much like the one TV execs once envisioned for so-called ÔÇ£quality televisionÔÇØ: people so ambivalent about the medium they might actually buy a line like, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs not TV, itÔÇÖs HBO.ÔÇØ

Of course, that phrase has Don DraperÔÇÖs fingerprints all over it, which is part of the reason Mad MenÔÇÖs odds may be due a reappraisal. The Wire may be TVÔÇÖs last word on inner-city crime and civil institutions, but in taking on sixties advertising, Mad Men takes on America itself ÔÇö currently a culture, industry, government, and society driven and sustained by marketing. As Mike Nichols recently told New York, ÔÇ£Now everyone in America is a salesman.ÔÇØ

If the fight went only one round, Mad Men would have it sewn up, had it the moment AMC wormholed Jon Hamm in from whatever Jim Thompson novel he was simmering in, wardrobed, Brylcreemed, and genetically destined for the glory that is Don Draper. That pilot-opening pan across a smoky restaurant found a man sitting apart, jotting down ideas on a cocktail napkin ÔÇö his angular features, vertical frame, and sharkskin sprezzatura would somehow always seem shot in black and white.

Draper may be mad, but heÔÇÖs definitely a man, a specimen of postwar Homo Americanus that we always suspected walked the Earth before the Surgeon General or Betty Friedan sanitized our public record. This kind of man staves off cancer and cirrhosis with a dyspeptic squint and a thoughtful drag, walks a daily mental gauntlet between RussiaÔÇÖs ICBMs and the nosecones of a steno-pool Venus, and finds greatness as the adman Dr. House, diagnosing the American psyche with each campaign. DraperÔÇÖs exalted spiel to the Lucky Strike folks didnÔÇÖt just neutralize carcinogens, it gave a grand slam pitch for Mad Men itself, promising a show with a giddily perverse intellectual energy, one tethered loosely enough to real history so that it jibed with some viewersÔÇÖ dimmest childhood memories.

The late-episode brainstorm with its two-word coup de grace┬á(ÔÇ£TheyÔÇÖre toastedÔÇØ) augured a show that would pit ad-savant Don Draper against the seismic changes of the sixties, with our flawed hero cracking a new account each week.┬áA few episodes in, as the complications of DraperÔÇÖs duplicitous home life were further complicated by his secret identity as Dick Whitman (adding momentum-killing expository flashbacks to the various diversions into other Mad folksÔÇÖ lives), it was clear Mad Men skewed more soapy than procedural.

But it took many male viewers a lot longer to grasp that Draper wasnÔÇÖt the good guy. It wasnÔÇÖt his guilt-free smoking, boozing, and womanizing they coveted so much as his deadly bead on society. His fake identity only seemed necessary to enforce this outsiderÔÇÖs gaze, a quality Rachel Menken ÔÇö sex-bomb Jewess-heiress to a Henri BendelÔÇôish department store ÔÇö spotted over drinks, nearly claiming him as a landsman.┬áA quality thatÔÇÖs apparently crucial to maverick adman and homicide cop alike.

ItÔÇÖs striking to see how similarly The Wire introduces DraperÔÇÖs counterpart at Baltimore PD. As played by HammÔÇÖs peer in studliness Dominic West, Detective James McNulty presents as a dashing, obsessive, alcoholic alpha who knows how to sell, how to charm, and how to get his rocks off, if not always how to stop; he takes an executive gangstaÔÇÖs courtroom victory so personally that he kicks a bureaucratic hornetÔÇÖs nest, which gets him more haters in law enforcement than organized crime. Both shows get us on the rogueÔÇÖs side right in the opening scene, with the same surefire tactic: having them converse as equals with black men of lower status. DraperÔÇÖs fact-finding chat is with a reticent waiter; McNultyÔÇÖs with a kid at the crime scene. Both shit-shootings veer Socratic, with one freethinker flouting his eraÔÇÖs conventions against conversing with black staff, the other flouting conventions against white-cop/projects-kid conversation of any kind, with both pairings aligning against a common enemy. In The Wire, the mutual antagonists are a new crime regime that has violated a morality that binds cop to hoodrat to the others whoÔÇÖll be drawn into the seasonÔÇÖs arc. In Mad Men, theyÔÇÖre the killjoys who rob men of simple pleasures, the natural foe of ad-exec and waiter: women. ÔÇ£I love smoking, my wife hates it,ÔÇØ the waiter tells Draper, their chuckle melting a whole race-class ice floe. But the different battle lines obscure the common playing field: a workplace that consumes everyone and everything involved, where family is a liability, product must always move, and skill and power come with deformation of the soul. Characters are defined by how they navigate their professional lives and, besides Draper, Mad Men has two great such navigators, and, ironically, they are both women.

One, Joan Holloway, announces ├£ber-female status with sheer physical presence; when dark awareness comes, itÔÇÖs not through changing gender roles, but the revelation that her male cult members are children: As Roger Sterling sinks from rebound-husband material to unweaned baby and then virtual mirage, his charm (and the audienceÔÇÖs interest in him) fades like smoke rings. The other great Mad woman, Peggy Olson, seems named for a staffer at The Daily Planet, though she takes some sharp detours from moral center. After successfully overlooking a potential career obstacle all the way through labor, she greets the nurse-borne swaddled newborn with a silent, placid gaze then turns away toward the window, and Elisabeth MossÔÇÖs childlike face ages twenty years with the cold, inhuman ambition that thrives in Brooklyn walk-ups as well as Baltimore housing projects.

Both shows have deep acting benches, and if Dominic West has Jon Hamm beat, itÔÇÖs solely for the difficulty score. Mad MenÔÇÖs lauded season-four episode ÔÇ£The SuitcaseÔÇØ paired the castÔÇÖs two biggest talents in a 47-minute Pinter play that revealed Peggy as yang to DraperÔÇÖs yin, and Hamm the kind of thoroughbred who can bound flawlessly through all five stages of whiskey bender: denial, anger, mouse-hunting, staggering, and office-menÔÇÖs-room puking. But West delivers a virtual dissertation on drunk acting in just one scene from The Wire pilot, as McNulty and Bunk lean against a parked car by the train tracks, trading marital woes in some of the most note-perfect drunken dialogue in TV history. All of which the British West performs ÔÇö down to the minutest speech delay and slightest focal vacancy ÔÇö┬áin a foreign accent, showing the innate mastery reserved to Englishmen. If you think about the tragic consistency of his character, whoÔÇÖs so McNulty his own kids call him ÔÇ£McNulty,ÔÇØ WestÔÇÖs The Wire performance takes on Soprano weight.

Characters arenÔÇÖt human beings, the typical inscrutable results of a million impulses and random events. But if McNulty is a character, heÔÇÖs still a human one and recognizable from beginning to end. Don Draper isnÔÇÖt always clearly an actual character. The shape-shifting locus of a show dizzy with image and spin, he is sometimes more a signifier from some new flashy campaign. When we see him midway through season four, heÔÇÖs in a locker room after a swim, hanging his head, gasping like a goldfish on the tiles ÔÇö a rough toweling leaving him not just hair-mussed but practically disfigured, a man who knows heÔÇÖs losing his edge. But when the bell tolls from a transistor radio, itÔÇÖs the 1965 No. 1 hit, ÔÇ£(I CanÔÇÖt Get No) Satisfaction,ÔÇØ a diegetic sound that becomes soundtrack, then libretto ÔÇö as Draper reconstitutes before our eyes. In a Reservoir Dogs slo-mo, the scene rebrands the adman Icarus whom weÔÇÖve always seen tumbling down a skyline to the sighing strings in the melodramatic opening credits. Scored by one of the toughest riffs of the last century, this man steps onto the street in a button-down whiter than your shirts could ever be, dons shades, and shakes out a cigarette whose kiss turns him into Montgomery Clift. To ÔÇ£I canÔÇÖt get noÔÇöÔÇØ he turns left profile to take in a street full of slow-moving marks, revealing the omnipotent figure who is twisting the songÔÇÖs singer into knots, the same man who will be doing the exact same thing, in different suits, with different music, as long as we play his game. (Hope you guessed his name.) ┬á

ItÔÇÖs some watershed when AMC buys not a Stones song but the Stones song for a scene recasting its villain as hero, the truest two minutes in a show that has been swallowed up by its subject. In retrospect, DraperÔÇÖs heady, essentialist adman spiel to Lucky Strike suggests creeping false advertising as he asserts that the art of promotion rests on just one thing: ÔÇ£Happiness,ÔÇØ Draper says, smiling like a kid on baseballÔÇÖs opening day. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs a billboard on the side of the road that screams with reassurance, that whatever youÔÇÖre doing, itÔÇÖs okay. You are okay.ÔÇØ┬á

You donÔÇÖt need an in-house Freudian to know this is more than slightly off. Advertising isnÔÇÖt about happiness; itÔÇÖs about fear, craving, and the other primal drives pinpointed by DraperÔÇÖs godfather (and FreudÔÇÖs nephew) Edward Bernays, when he founded advertisingÔÇÖs modern age on the fissures deep within the unconscious. Happy people who feel okay donÔÇÖt buy things they donÔÇÖt need; thatÔÇÖs what admen are for. And in some ways, Mad Men is as much an extension of modern advertising as commentary on it: It too flatters the consumerÔÇÖs sense of superiority, plays mini-documentaries celebrating early ads for BMW that are also ads for BMW. To revisit Mad Men is to occasionally feel bludgeoned by the sloshing rocks glasses, sparked cigarettes, pre-P.C. one-liners ÔÇö okay, okay, okay, we get it. No TV show should aspire to art, but few have been so celebrated for celebrating their own culture, for producing a gorgeously crafted, several-season spot whose one consistent message is ÔÇ£YouÔÇÖve come a long way, baby.ÔÇØ

To say the least, The Wire doesnÔÇÖt leave you feeling smug. If advertising has a polar opposite in TV drama, itÔÇÖs probably a show that told hard truths about subjects that drove the most important documentaries of the next five years (from Waiting for ÔÇ£SupermanÔÇØ to Inside Job to The Interrupters to Page One: Inside the New York Times). The show isnÔÇÖt about cops, killers, politicians, teachers, and newspapermen. ItÔÇÖs not even solely about American cities. In old cop lingo, ÔÇ£the wireÔÇØ didnÔÇÖt mean surveillance taps but the grapevine, and this high-voltage current of surveillance, misinformation, control, and seduction comprises our national nervous system.

The Wire was neither produced nor sustained by advertising, not even by HBOÔÇÖs stealth marketing campaign during its run. Of the many people I know whoÔÇÖve seen every single episode, none saw it on HBO. Its long tail grew through word of mouth, thanks to an open secret among devourers of the DVDs: If you pay attention through the first episode, you might be able to stop after the second. But after that, itÔÇÖs too late, youÔÇÖre turned out, with a two-episode-per-night habit. Whichever wag at Stuff White People Like put The Wire on its list must not take the same Bronx-bound 4 train that I do, where IÔÇÖve seen the showÔÇÖs logo on hoodies belonging to people who appear outside the demographic.

Why do we all like The Wire so much? Is it the ÔÇ£reality,ÔÇØ the ÔÇ£authenticityÔÇØ? (David SimonÔÇÖs rough-draft 2000 HBO mini-series The Corner had plenty and sank like a stone.) Or is it the kind of TCM-worthy filmmaking exemplified in season threeÔÇÖs pivotal episode ÔÇ£Middle Ground,ÔÇØ with its epic crane-shot opening on the lone figure of Omar Little, who whistles and walks dark, rain-slicked city streets like a western-district Harry Lime, until a voice in the dark makes him turn to face a gun aimed by a bow-tied Muslim assassin? With Tarantino dialogue and spaghetti-Western blocking, the two ideological enemies express equal power through knowledge of each othersÔÇÖ handgun ÔÇö Baltimore cowboyÔÇÖs Army .45 versus bow tieÔÇÖs Atlantic-reading Walther PPK ÔÇö finding a d├®tente that dooms a central character before the opening credits.

No set piece this badass belongs in any socially redeeming program. But despite the scores of them running through all five seasons, itÔÇÖs the more profound plot convergences within The Wire that leave a stronger impact. Like the one late in the third season, when three separate character arcs align at the same epiphany, all of them dumbstruck by the skill-, courage-, and strength-trumping power of Who You Know. McNulty gets his hard lesson from both barrels. First, heÔÇÖs rebuffed by a fuck-buddy political operative he briefly tries to date (in a dinner scene where an excruciating economy of dialogue sharply downgrades his own status). Next, his teamÔÇÖs byzantine organized-crime case ÔÇö a D.I.Y. masterpiece of┬ácutting-edge tactics, deft informer management, and inspired technical ingenuity ÔÇö gets undone by just one call by a mid-level wonk with a landline.

This is a French Connnection ending ÔÇö not an ÔÇ£upÔÇØ one ÔÇö and the seriesÔÇÖ actual ending is in some ways even more of a downer. But the show isnÔÇÖt. Not when the myriad connections between its characters and their different worlds cohere, and the breadth of its vista settles in the mind. Real-life people like dollhouse-miniaturist Lester Freamon, department-brass-shielded fuck-up Pryzbylewski, and shotgun-toting, gay dope-house robber Omar may exist, but their characters wouldnÔÇÖt mean as much if they didnÔÇÖt fit into such a coherent moral universe. When executive editor James Whiting hailed ÔÇ£the Dickensian aspect,ÔÇØ he did so in the final season of a show whose writers knew what theyÔÇÖd accomplished, when its scale recalled the case Lester Freamon saw cohering in season one, telling young Pryz: ÔÇ£All the pieces matter.ÔÇØ Crime novelists and reporters think of pieces and details, screenwriters of arcs and acts; the difference is visible in these two shows.

Because all the pieces matter, so much, The Wire tells truths that arenÔÇÖt ÔÇ£poetic,ÔÇØ ÔÇ£emotional,ÔÇØ or some other vogueish euphemism for ÔÇ£untrue.ÔÇØ TheyÔÇÖre truths, distilled from truthful observations over decades of life. Promoting his latest novel, The Wire writer George Pelecanos revealed that his early crime novels relied on the same tactic as the old-school policing advocated by season fourÔÇÖs Sergeant Carter: standing out on live drug corners and talking to everyone he could. Today, he fields requests from hustlers, users, and other street-level players to tell their stories from todayÔÇÖs drug-ravaged Baltimore. The lives in Mad Men are compartmentalized, their segments fit between commercials, and weÔÇÖve yet to see if the show leaves us with any larger insights about our moment. While its lingering melancholy makes for ineffective marketing, the metropolis that The Wire wove together with unprecedented patience and honesty left us with one killer tagline of a message. ItÔÇÖs that any good thatÔÇÖs done today will get done in secret, off the clock, by a few obsessive headcases, probably defying direct orders not to do it. America does not run on DunkinÔÇÖ. It runs, when it runs, on these people.

Winner: The Wire

Chris Norris has written for New York, The New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, Film Comment, Spin, NPR, and other outlets. He is co-author of the New York Times best seller The Tao of Wu with Wu Tang Clan mastermind RZA.