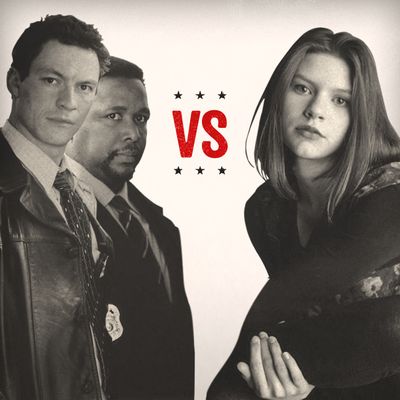

For the next three weeks, Vulture is holding the ultimate Drama Derby to determine the greatest TV drama of the past 25 years. Each day a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until New York Magazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 23. TodayÔÇÖs battle: Davy Rothbart judges The Wire vs. My So-Called Life. You can place your own vote on Facebook or tweet your opinion with the #dramaderby hashtag.

In high school, the only girl who really understood me was Angela Chase. Granted, she was just a TV character. But as played by Claire Danes on My So-Called Life, Angela was sweet and curious, and had an open-hearted compassion that made me feel like IÔÇÖd found a soul mate ÔÇö even if I could never speak to her in real life.

It has been more than fifteen years since IÔÇÖd watched Life, and I was unprepared for the intensity of my response as I re-immersed myself in AngelaÔÇÖs world. The show, which aired from 1994 to 1995, follows 15-year-old Angela as she navigates her high schoolÔÇÖs social minefields, swoons over brooding hunk Jordan Catalano (Jared Leto), and attempts to steer her friends and family through lifeÔÇÖs unpredictable tides, which she does with great intelligence and sensitivity. Rewatching the show, IÔÇÖd hoped for a nostalgia trip, and maybe the opportunity to check back in on an old teenage crush ÔÇö unlike other past loves, Angela Chase doesnÔÇÖt seem to be on Facebook ÔÇö but I never expected to find myself so moved, delighted, and utterly absorbed. More than once, someone knocked on my door and I had to somehow explain why my eyes were wet.

That My So-Called Life remains so affecting is thanks in no small part to its highly relatable characters. ThereÔÇÖs Angela herself, of course, still effortlessly endearing. Her expanded universe consists not only of the doe-eyed, mysterious Catalano, but also her parents, Patty and Graham; her neglected little sister, Danielle; and her friends Rayanne Graff (the wild one), Rickie Vasquez (the sensitive, gay one), Sharon Cherski (the square), and Brian Krakow (the high-achiever whoÔÇÖs not-so-secretly in love with Angela). These are all recognizably complicated souls who aim to do right, but often stumble along the way, their attempts at kindness invariably leading to injury.

Life wasnÔÇÖt just about high schoolÔÇÖs hallway dramas. While most teen-centered shows fail to infuse the kidsÔÇÖ adult foils with their own set of feelings and impulses, one of LifeÔÇÖs triumphs is the rich, fully realized characterizations of AngelaÔÇÖs parents: Graham struggles to find meaningful work and wrestles with the idea of pursuing another woman. Patty, meanwhile, deals with the undermining energies of her own mother and father, reminding us that friction between children and their parents is an ongoing part of life, not just adolescence. More than once, Patty or Graham asks the other, ÔÇ£Did we do the right thing?ÔÇØ and the apparent answer is that there is no right answer ÔÇö that, painfully, our moral universe will always be messy and gray, even when we become grown-ups.

I was also struck by the beauty of the showÔÇÖs silences and stillnesses, and by the looks of surprise, sadness, and betrayal on the charactersÔÇÖ faces, which frequently go unnoticed by others, often in searing ways. IÔÇÖd simply forgotten what itÔÇÖs like to share a house every day with your parents and siblings, and how completely the dynamics of a family (the loneliness, the camaraderie) can dominate your being. Reviewing LifeÔÇÖs nineteen episodes brought it all back with a pinching bittersweetness I hadnÔÇÖt anticipated.

Much of the credit here goes to My So-Called LifeÔÇÖs creator, Winnie Holzman, an unflinching humanist with a canny eye for the minute thorns and prickles of adolescence. The tension is expertly wrought: By showing us exactly what Angela is feeling, and giving us private insight into the people around her, Holzman has set her phasers permanently on Squirm-in-Your-Seat. We know, for example, that Jordan has slept with AngelaÔÇÖs best friend Rayanne long before she does, and as the truth of it slowly dawns, itÔÇÖs painfully cringe-inducing to watch.

Life is set in suburban Pittsburgh, not Beverly Hills, and one of the showÔÇÖs conceits ÔÇö practically groundbreaking at the time ÔÇö was to reflect actual middle-class concerns to its middle-class audience, discarding the aspirational timbres of 90210. Characters struggle: Rayanne has a drinking problem, Jordan is nearly illiterate, and Rickie wrestles not only with coming out, but with abuse and homelessness. The path the series walks, as AngelaÔÇÖs knowledge of her new friends expands, is of her awakening from childhood ÔÇö in all its blissful safety and comfort ÔÇö to the tribulations and unsettling mysteries of adolescence and adulthood.

It could be said that our country, in the mid-nineties, was walking that same path, from the Reagan EraÔÇÖs opiate smile and willfully ignorant haze to the troubled questions of the Clinton years: Why are we bombing Belgrade? Why did Kurt Cobain blow his head off? Why is the president getting his knob shined in the Oval Office? For Angela Chase and her family and friends ÔÇö and by extension, us ÔÇö lifeÔÇÖs quandaries may have no clean-cut solutions, but compassion and honesty are our most durable torches to guide us through the night.

Drive four or five hours southeast from AngelaÔÇÖs hometown of Three Rivers, Pennsylvania, and youÔÇÖll reach the industrial port city of Baltimore, Maryland, the setting ÔÇö and in some ways the main character ÔÇö of David SimonÔÇÖs sprawling, ambitious, anthropological HBO series The Wire, which aired from 2002 to 2008. Simon drew on years of experience on the homicide beat of The Baltimore Sun, pulling back the curtain on the flawed institutions that make up a city with barbed wit and no-holds-barred detail. The works of Balzac, Dickens, and Dostoevsky were among SimonÔÇÖs inspirations, as evidenced by The WireÔÇÖs deeply literary tone, nuts-and-bolts societal revelations, and ceaseless moral inquisitiveness. It easily tops any cop show before or since.

Generally, youÔÇÖve either seen The Wire and have a cultish appreciation for it, or you havenÔÇÖt seen it and are mystified by all the fuss. I was in the latter camp for many years, and it wasnÔÇÖt until the series was off the air that I finally dug in, binged on the DVDs, and quickly became a convert, understanding the unabashed loyalty from super-fans. The Wire combines the appeal of insightful, detailed, long-form journalism and the entertaining, page-turner charms of the best pulp novels. As grim and ponderous as the series could become, its cat-and-mouse gamesmanship was entrancing, and its procedural beats were made vivid through playful asides, like the police superior obsessed with dirty magazines.

Season one introduces the Barksdale criminal organization, led by Avon Barksdale (Wood Harris) and his right-hand man Stringer Bell (Idris Elba), who together operate a powerful drug gang in the West Baltimore housing projects. But it gives equal time to the team of cops devoted to bringing Barksdale down, including the talented, boozing, renegade Jimmy McNulty. Played by British actor Dominic West, McNulty is a swashbuckler with a badge, and his raffish charm provides viewers with an obvious rooting interest. His battle, though, is not only against the Barksdales, itÔÇÖs against his superiors in the department, whose inflexibility, bald political aspirations, and rigorous devotion to ÔÇ£chain-of-commandÔÇØ groupthink all serve as barriers to his inventive police work.

In each season of The Wire, that central conflict is replicated: One man, with ultimately honest ambitions, is unable to penetrate the corrupt DNA of the institution he works for. Union workers, mid-level police commanders, the mayor, even the dealers themselves ÔÇö they all struggle to thwart bureaucracy without surrendering their ideals.

The Wire is populated with so many indelible characters, devotees of the show will light up (or grimace) at their names alone: Bunk, Valchek, Greggs, Lieutenant Daniels, Frank Sobotka, Ziggy, Prez, Beadie, Marlo, Snoop, and dozens more. That even the most minor characters have major followings is testament not only to the seriesÔÇÖ outstanding writing and perfectly crafted roles, but also the devoted, fully inhabited performances of its stellar cast, comprised mostly of little-known actors. Perhaps no character developed a more enthusiastic following than stickup man Omar (Michael K. Williams), the gay, laconic, Wild West badass whom you feared and rooted for in equal measure. Even President Obama has cited Omar as his favorite Wire character.

Though The Wire is thick with betrayal and sabotage, I find the most painfully incisive story threads to be the ones in which the city swallows up its most innocent victims. In season four, we meet a troupe of young teens ÔÇö kids only a grade or two behind Angela Chase and her friends ÔÇö who fight to resist the pull of the street. That these sweet, smart street kids are likely to meet dark ends feels terrifyingly inevitable, even as we hope with all of our might for something brighter. But it was never David SimonÔÇÖs intent to create pop delights or to let us off the hook easy. The Wire, instead, is more of a political manifesto, incriminating those of us who might prefer to look away from societyÔÇÖs failures.

The Wire is not pure nihilism, though, and I would argue that SimonÔÇÖs anger and frustrations are not mutually exclusive to the kind of hopefulness on display in My So-Called Life. As disappointing as the institutions might be that continually fail their faithful (if jaded) worker ants, the gallows humor and in-the-trenches camaraderie between co-workers ÔÇö be they cops, teachers, drug dealers, or politicos ÔÇö shines in bright relief. We may be going down in flames, many of the characters seem to be saying, but at least we know that IÔÇÖve got your back, and youÔÇÖve got mine. And while Jimmy McNulty commands the most screen time, I consider homeless basehead Bubbles (Andre Royo) to be the showÔÇÖs raw, beating heart. Despite all the tragic, battering turns he suffers and cruel hands heÔÇÖs dealt, Bubbles finds a way to overcome his addictions and reach a muted, understated glory. More than McNulty, perhaps, Bubs is the storyÔÇÖs everyman, and his triumph suggests that thereÔÇÖs hope for us all.

So, which is the better show, My So-Called Life or The Wire? As Senator Clay Davis would say, ÔÇ£Sheeee-eeiiiit.ÔÇØ ItÔÇÖs a tough call.

The shows are vastly different in both tone and scope. In some ways, the comparatively pared-down cast of My So-Called Life creates a deeper engagement with its characters, allowing for greater emotional stakes. Small moments feel downright epochal on Life, and for me, the most gripping and powerful moment of either series was when Jordan Catalano clasps AngelaÔÇÖs hand for the first time in the hallway at school. But Life can get too emotional at times, leaning a bit hard on AngelaÔÇÖs voice-overs, which can occasionally feel cloying, overly self-involved, or simply unnecessary. And the gravity of certain scenes feel a little out of whack: Many of the charactersÔÇÖ concerns ÔÇö unrequited crushes, bad grades ÔÇö are ultimately trivial. I donÔÇÖt see Avon Barksdale or Stringer Bell freaking out about a zit. TheyÔÇÖve got bigger fish to fry.

On the other hand, when a story line can be manipulated with the pull of a shotgun trigger, gunplay and violence can become a narrative crutch, and The WireÔÇÖs surging body count as the series progresses can sometimes create fatigue. And itÔÇÖs possible to get lost here and there in The WireÔÇÖs narrative thickets, and its pace occasionally stalls.

And as rooted in real life as The Wire aims to be, there are certain story lines that strain credibility. In season five, McNulty, upset by the departmentÔÇÖs dwindling resources, concocts a serial killer, faking murder scenes and planting false evidence. His efforts begin to pay off, as heÔÇÖs finally offered the manpower he needs to pursue the drug kingpins who are his true target, but it becomes increasingly hard to believe that any cop ÔÇô even one as maverick as McNulty ÔÇô would go to such bizarre lengths to bring down a suspect. My So-Called LifeÔÇÖs constant eye toward plausibility is a point in its favor.

But one of The WireÔÇÖs most impressive feats is its refusal to sort its characters into heroes and villains. McNulty, for all his pluck and charm, is also revealed to be, at times, an unfaithful drunk and an unreliable dad. Avon Barksdale, though unapologetic when putting a price on the head of a friend or a family member, can also show unexpected generosity and compassion, as when his enforcer, Cutty, tells him he wants out of the game. Barksdale ÔÇö who has proven in the past just how ruthless and remorseless he can be with disloyal subjects┬áÔÇö gives him his blessing, and even contributes $10,000 to a neighborhood boxing gym that Cutty has opened for local kids. Persuasively, in The Wire, even the most ethical characters have moments of weakness, and even the most evil and corrupt can surprise you with their decency.

The truth is, both My So-Called Life and The Wire are titans, and they each got a tough break drawing each other in the first round. Ultimately, My So-Called Life is at a fundamental disadvantage, since the show was canceled after a single season, while The Wire ran for five. Winnie Holzman had big plans for future seasons (pregnancy, depression, the threat of divorce) but these were buried by the TV executives who gunned the show down and tossed it in the ÔÇ£vacants,ÔÇØ even as its loyal, devoted audience rose up in arms to defend it (the first movement of its kind). As The Wire later demonstrated with such cruel efficiency, our misguided, misdirected institutions rarely have qualms about crushing the most pure of spirit, and commercial television is no different.

Had My So-Called Life had the chance to run its course, itÔÇÖs hard to say for sure who might have prevailed here. As it is, The Wire, in its epic scope and brilliant execution, is the greater body of work, and to be honest, will be hell for any series of any era to face down. In my humble opinion, as Angela Chase would say, I consider it the greatest TV show ever made, and I know IÔÇÖm not alone. Care to disagree? Cool. IÔÇÖll send Snoop right over.

Winner: The Wire

Reader Winner as determined on VultureÔÇÖs Facebook page: The Wire

Davy Rothbart is the author of the essay collection My Heart is an Idiot, which comes out Sept. 4. He also runs an annual hiking trip for inner-city kids called Washington II Washington.