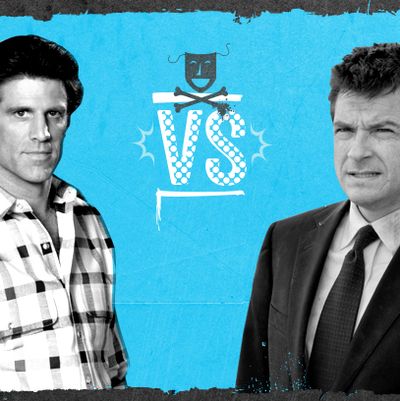

Vulture is┬áholding the┬áultimate Sitcom Smackdown to determine the greatest TV comedy of the past 30 years. Each day, a different notable writer will be charged with determining the winner of a round of the bracket, until┬áNew York┬áMagazine TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz judges the finals on March 18. Today we begin the quarterfinals with New York MagazineÔÇÖs own Will Leitch pitting the classic Cheers against the returning hero Arrested Development.┬áMake sure to head┬áover to Facebook to vote in our Readers Bracket, which has already veered from our criticsÔÇÖ choices. We also invite tweeted opinions with the #sitcomsmackdown hashtag.

As an obsessive consumer of mass entertainment, I often find myself envious of those who are not. People who havenÔÇÖt seen everything literally donÔÇÖt know what theyÔÇÖve missed. When someone tells me theyÔÇÖve never watched Casablanca, I wish I could be them, to have that sense of discovery. Every time a great movie ends, I get depressed: I can watch it again, but it will never be like the first time. There should be a word for that feeling.

My two exceptions to this happen to be the shows IÔÇÖve chosen to compare: NBCÔÇÖs Cheers and FoxÔÇÖs Arrested Development. If either one of them is on, at any time, I stop everything and stare, giddily. I own every episode of each and use them, essentially, as pain relievers: They are guaranteed to fix whatever ails me. They make me want to crawl into the television. They are like visiting long-lost loved ones. They are like going home.

The shows are superficially different. Certainly the pacing of each is of their era; CheersÔÇÖ (1982ÔÇô1993) patter felt rat-a-tat at the time but is downright glacial now, while Arrested Development (2003ÔÇô2006) is constantly jumping to and fro, an eager puppy worried it will lose your attention. Cheers is straightforward and reassuring; you fall into it like you would your oldest, most comfortable chair. Arrested Development is nervy, self-referential, and self-aware. The writers made inside jokes about mediocre ratings (ÔÇ£Maybe people donÔÇÖt like the Bluths!ÔÇØ), FoxÔÇÖs irritating scheduling decisions, and the showÔÇÖs eventual cancellation. The supremely meta AD commented on itself in ways that Cheers, which existed outside space and time, never would.

Deep down, though, they are the same show. They are both about a family ÔÇö one literal, one chosen ÔÇö with a central figure that everyone relies on, whether that figure likes it or not. Cheers is more openly sentimental, but one of the least heralded aspects of Arrested DevelopmentÔÇÖs greatness is how warmhearted it is. Michael Bluth never leaves his intensely dysfunctional (and woefully unappreciative) family, just as Cheers owner Sam Malone never seriously considers abandoning his bar or the lovable losers who sit around it, day after day. The arc of the characters, such as it is, is ÔÇ£We are all in this together, no matter how badly anyone behaves ÔÇö though we do reserve the right to laugh at you.ÔÇØ The best episodes of each series highlight a characterÔÇÖs most annoying qualities, at which point we mock, then forgive them. Of course Cliff Clavin tries to get away with blowing his whole wager on Jeopardy! by noting that Cary Grant, Tony Curtis, and Joan Crawford have never been in his kitchen. Of course Tobias F├╝nke would think that an audition for a fire-sale commercial would feature him acting as if heÔÇÖs in an actual fire. ÔÇ£Oh my God, weÔÇÖre having a fire ÔǪ sale.ÔÇØ (Now that I think about it, Tobias is kind of the Cliff of Arrested Development.)

Note that I couldnÔÇÖt help myself there: I quoted an Arrested Development line. ItÔÇÖs impossible not to do that; Arrested Development wrested the quotability torch from The Simpsons ÔÇö just check out the insanely popular @bluthquotes. Still, IÔÇÖm betting that if Twitter had existed during CheersÔÇÖ run, you could have fueled several accounts with Norm, Woody, Diane, and Carla quips. (Someone should do that, actually. Maybe I should.)

Both shows did an impressive job of distributing classic moments within a big cast. But the world of Arrested Development was a little bit larger; much like The Simpsons (again), it had a universe of peripheral characters, from Bob Loblaw to Thomas Jane to Franklin to the editors of Poof! magazine. Other than occasional battles with those jerks from Garys Olde Towne Tavern, Cheers mostly stuck to the bar, just the staff and regulars talking and talking and  talking. That is, after all, what made Cheers Cheers. And because we stayed in the bar, there was a lot we didnt know about the characters exterior lives, and the questions those omissions raised became, oddly enough, one of the shows most enjoyable aspects. What does Norms wife, Vera, look like? Why is Cliff wearing his postal uniform on Sundays? How in the world do the regulars hold down a job when they are always in a bar? Why does no one ever pay for a drink? Why is no one ever drunk?

The temptation is to give Cheers bonus points for innovation and influence, but (a) Arrested DevelopmentÔÇÖs influence is still spreading and surely will continue to do so (Modern Family is essentially a less daring, less funny Arrested Development, and itÔÇÖs still a pretty good show), and (b) that does Cheers a huge disservice, implying that the praise is some sort of lifetime achievement award. Cheers can stand on its own without extra credit. People copied it because it was so wonderful, after all.

More problematic is weighing the shows in terms of popularity and longevity. On one hand, Emmy-winning and critically beloved Arrested Development barely made it three years, and in retrospect, it seems amazing it lasted that long: The show was watched by a piddling 6 million people its first and second season, and only 4 million tuned in for season three. (Watching AD in real time felt like magic ÔÇö like they were getting away with something by staying on the air.) Cheers, on the other hand, is one of the most highly rated shows of all time, remaining in the top ten for eight of its eleven seasons; critics and viewers loved it. It was so popular that Kelsey Grammer, who played Frasier Crane, has talked about being threatened on the street for keeping Sam and Diane apart.

Obviously, the two shows aired in wildly different eras of broadcast television; network numbers tumbled from the nineties on, thanks to the Internet and edgier cable shows. But Arrested Development (and, similarly, 30 Rock) was so experimental and inside baseball, it probably never could have been a mainstream hit. And that, in turn, is a big reason why the showÔÇÖs cultlike followers remain so obsessed with it: You have to really know TV and pop culture to get a lot of what is going on ÔÇö thatÔÇÖs part of the fun. Some might argue such narrow appeal immediately disqualifies Arrested Development from this greatest ever race. To them, I say: Nuts.

Basically, you wonÔÇÖt convince me these arenÔÇÖt the best two sitcoms of the past 25 years, the rest of this bracket be damned. Choosing between them is like choosing between your children, assuming both your children are awesome.

I find myself declaring Cheers the winner, for two reasons.

1. Longevity. Different TV landscape or not, to be that terrific for eleven seasons  to survive dramatic cast changes, producer attrition, the fickle tastes of America  is nearly unheard of. Not every episode was perfect  but frankly, most were.

2. Series finale. By the end, Arrested Development felt a little desperate, with altogether too many jokes about its own cancellation; all told, that third season wasnÔÇÖt as strong as the first two. But the last season of Cheers remains flawless, right down to its graceful last step. The final episode, available in its entirety on YouTube, ends with our old friends gathered around the bar, smoking cigars, drinking, talking about the meaning of life, and love, and what it means to be happy. (Cliff says itÔÇÖs comfortable shoes, and, for once, IÔÇÖm not sure heÔÇÖs wrong.) Cheers knew exactly when to call it quits, and they did it in precisely the right way.

Now, if youÔÇÖll excuse me, IÔÇÖm gonna celebrate the decision with a Screaming Viking.

Winner: Cheers

Will Leitch is a contributing editor at New York Magazine.