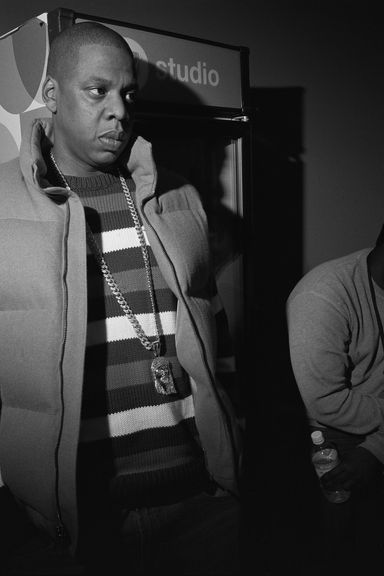

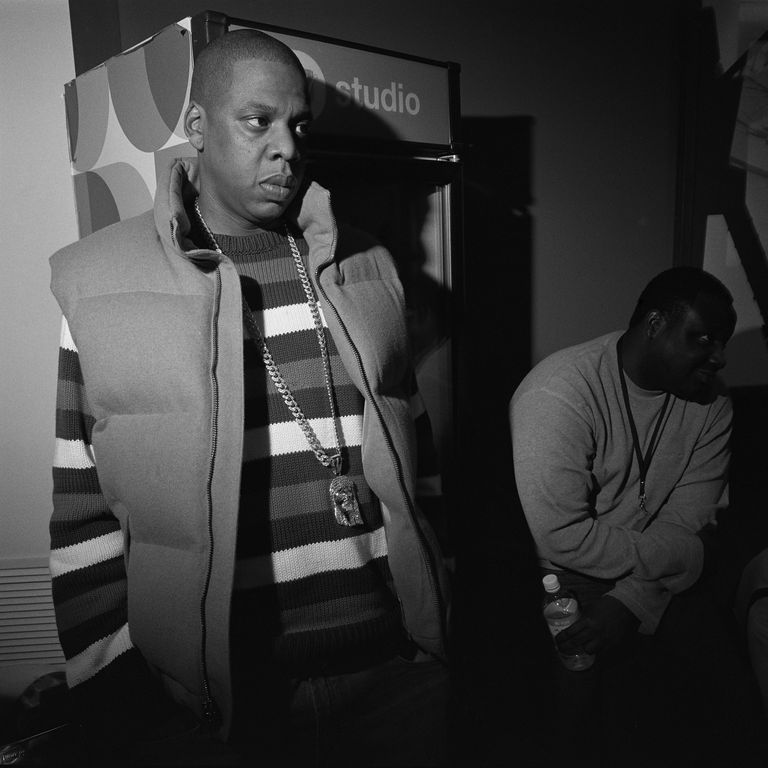

Larry Fink, the Counter-Culture Artist Turned Celebrity Photographer

Larry Fink juggles numerous titles: He’s a farmer living on a barn in Pennsylvania with his artist wife, Martha Posner; a professor of photography at Bard College; a self-proclaimed humanist; a father; and a photographer — one who’s gained industry-wide acclaim for shooting the most exclusive parties and backstage events swarmed by the cultural elite (think Oscar parties and fashion weeks). But Fink delights just as much (quite possibly even more) in shooting the opposite end of the spectrum; insects, boxers, and “death masks,” for example. Considering that he’s been shooting for 57 years (having first been seduced by the camera at age 12), it’s safe to say he’s taken his lens down every path his interests have led him. In addition to contributing to Vanity Fair, W, GQ, Detour, The New York Times Magazine, and The New Yorker, he’s also published eight monographs of his work.

Though he never finished college, Fink has exerted quite an influence on many generations of photographers through his work as a teacher. After picking up his first teaching job in 1963 in Harlem, he later became a professor at institutions like Parsons, Cooper Union, Yale, and Bard, the last of which he claims he’s “been at for 100 years.” The Cut spoke with Fink over the phone about his younger years growing up in a Marxist home, his perspective on teaching, and shooting the fashion and celebrity scenes. He spewed out a bounty of choice phrases (e.g., “I like the constellation of the sun and the stars being happy while they fertilize each other” while describing his appreciation of jazz) — and even though he’s a deep thinker, he never got too serious. For every philosophical musing about culture and humanity, he’d erupt in giggles at a delightful detail previously buried in a memory. Click through the slideshow to delve into the stories behind his photos, and read the Q&A below for his point of view on “violence in fashion,” his first time working for Graydon Carter, and his current projects.

You were studying to be an artist for a bit. When did you decide to go into photography as a career?

I didn’t go to school. I never went to college, except for a couple of months, but I used to go up to the Metropolitan, and I studied [paintings]. Then I got to a certain point, to be friends with Dore Ashton, the great art critic, who’s still teaching at Cooper Union. I got acquainted with folks like Saul Steinberg and many of the abstract expressionists, so I expanded my vocabulary way beyond the realism that photography has, and also the realism that my folks were most in favor of, being the socialist types.

Did you always know that you wanted to teach? Or was that something that you just fell into?

For me, kind of being a left-wing guy, I always thought that was part of the revolution, if you will. I still think that. Not that there’s any revolution in sight, but there is always a revolution for the human imagination and for the soul. And today, in a very commercial word, with the banking crisis becoming more and more powerful, it’s more and more important to ask the kids about their imaginations, and about their character, and about the humanness of experience. The hopes for the fact of our humanness and for our imagination.

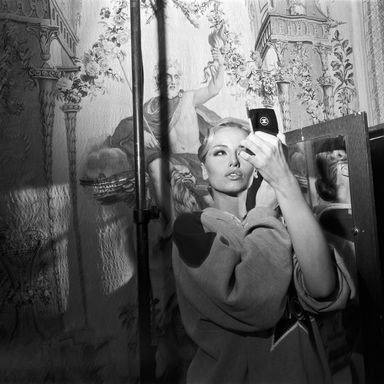

You’ve shot quite a few fashion shows. Do you have any memorable fashion week moments?

In the book Runway, Guy Trebay really coined it up really well: “You wouldn’t think of fashion as a world full of violence, but it is.” The violence of obsolescence and the incredible back-biting of cultural roar. There was a lot of that, and I was very much a part of that world because I was there on the scene, carrying on. But I didn’t feel personally part of that scene at all. I wasn’t wearing Armani suits, you can be sure of that. Actually, during the heyday, I went into a fancy shop to price a suit, which I would never wear, but I thought I should have a suit. They were so expensive that I ended up buying a tie. [Laughs.] So, I have a good-looking tie that cost $50.

Could you expand on what you referred to as “violence”?

There were innuendos that go on back and forth between the models and the designers, and the amount of anxiety. I used to call fashion weeks ‘Theater without a Plot.’ In real theater, you have a plot where people really move forward in a very empathetic way to see whether they can fulfill the real personality of the character. There’s a great deal of quest for human understanding. In the fashion world, this is not the case. Once upon a time, way before Marc Jacobs worked with Juergen Teller, one of his guys came up to me at a fashion show and he said, “Marc Jacobs loves your work.” And if I was an ambitious guy, a guy with a head for that sort of thing at that point, I would have made an appointment with him right away, and perhaps I would have become a millionaire, perhaps like Juergen Teller is. But I said, ‘Oh, thats great,’ and went on with the program. So I missed my making [laughs].

It seems like you were never fully steeped in the fashion world.

No, not really. I did enjoy it, I have to tell you. My mother was a Marxist. She was also a very elegant gal, and she wore mink. She quit the Communist Party because they were too focused on regime, and she liked beautiful and fine things, and they didn’t. They kept on berating her, even though she was a magnificent organizer. I was a Mink Marxist too, which is to say that I was also attracted to voluptuousness and parties and fine things, but always one step away. I was always alone. Actually, Carine [Roitfeld] came up to me at a party and said, “Why do you always have that very, very gleaming smile on your face?” It’s because I had a secret, and the secret was within.

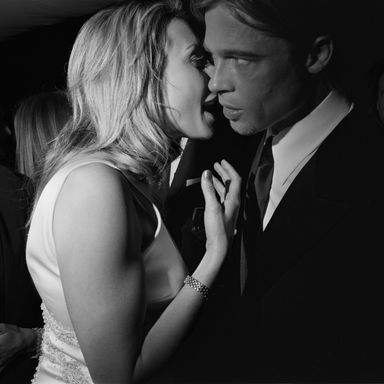

Party shooting is also a niche you became well-known for. What was your first experience shooting high-profile parties like?

I was real anxious because I was working for the first time for Graydon [Carter] and for Vanity Fair, and I didn’t know exactly what to do. I wanted to please them as a responsible photographer. But as far as being in the room with all these fancy folks, or famous people, I don’t care about that at all. The first time I went out to Hollywood, I’d never worn a tuxedo in my life, and we were sitting around in at the pool in Beverly Hills and [Graydon] says, ‘What are you wearing tonight, Larry?’ And I said, ‘Probably what I’m wearing this afternoon.’ He said, ‘Oh, no.’ [Laughs.] So Dana Brown, who now is an editor, but was Graydon’s assistant at that time, was assigned to take me down to the tux shop and get me all suited up, and rented a tux so I could be appropriate. So that was my first experience. I absolutely, always wear a tux to an Oscars party.

You said you were never nervous or intimidated around celebrities. Was capturing celebrity culture exciting to you or interesting back then?

I had fun. I was very interested in power. So I was photographing Wall Street at a certain point, and then the parties and various aspects of power. It’s not that the stars in that particular world are powerful, but they’re not necessarily corrupt. But they are, in a way, the crème de la crème of elegance, and so it was a natural progression for me to be totally interested in coming to terms with that as subject matter. Plus, the fact that it was a great contract and great work. I lived in a way that I never thought was even possible for me. The flights and hotels and all that kind of junk. Do I miss it? No. I fly coach now! [Laughs.]

What projects are you working on right now?

I’m photographing a family here in Pennsylvania who’s a lot like the Sabatines, the family in Social Graces, but equally as pithy, but with much more goodness in tact. I’ve been photographing for the last several years what you would call “the death masks” in gravestones. But I’m not just photographing the sculpture itself, I go into the faces with the little macro lenses and reinterpret them and try to, in a way, breathe life into them from within the stone to make the visual interpretation something a little bit more palpable. I’ve been working with just the human eye and face to see if I can bring — the series is called “Flesh and Stone,” and breathing life into the stone and not necessarily breathing death into the flesh, but having some kind of coordinate and putting them together so that there’s some kind of reflective relationship.